This story about Calgary’s Derek Pauletto and Trillion Industries was first published in Motorcycle Classics magazine. All photos courtesy Kurtis Kristianson and Spindrift Photography.

There’s a trend emerging in the motorcycling community, one that sees relatively unloved classic machines transformed into something the original maker would never have imagined. Many online forums and blogs showcase cleverly designed choppers, bob jobs and café racers, and plenty of them are based on motorcycles of the late 1970s and early 1980s that originally didn’t have much grace. Take the humble Honda CB650, a four-cylinder model sold in North America from 1979 to 1982. Honda produced thousands of these motorcycles, yet how many of us remember them? Honda’s CB650 didn’t have the charm of the smaller CB550, or the power of the larger CB750. No, the CB650 just isn’t considered an important motorcycle.

That’s not to say it isn’t a good motorcycle, though. Calgary, Alberta welder and fabricator Derek Pauletto learned just how reliable his 1979 Honda CB650 could be after he bought it for $300 from a co-worker’s older brother. The first time he laid eyes on the CB650 the machine was outside, leaning up against a garage. Covered in leaves, the Honda had obviously been exposed to the elements for a few months, but it had brand new tires – hence the $300 asking price.

“I wasn’t attracted to it, and it wasn’t my style,” Derek says. At the time, Derek was interested in more modern, streamlined equipment, but adds: “I thought I might be able to get the thing running, and I didn’t have a complete bike to ride at the time,” It took him only a few short days to sort out the carbs on the CB650 before it roared to life, and Derek began using it to commute to his last year of welding classes at tech school, and to his job at a local welding and fabrication shop. While at this shop Derek became known by vintage motorcyclists for his skill with a TIG welder, and his ability to bring back from the dead almost any cracked or otherwise destroyed piece of aluminum, including British motorcycle engine cases and primary covers. Derek now runs his own shop, Trillion Industries, and he continues to be a go-to guy for alloy welding repairs.

But for those two years the CB650 proved to be dead reliable, always starting on the button and never protesting. It was easy on gas, and cheap to run, but when Derek finished putting together a 1988 Honda Hawk GT project for himself he was prepared to sell the CB650. So he stuck a $500 price tag on it, and waited for a buyer. None ever arrived. Neither did they at $400, or even $300.

“Friends were laughing at me that I wanted that much money for it, and were telling me I was wasting my time trying to sell a motorcycle like that,” Derek says. “But that CB650, it had gotten me from A to B, and I had ridden it for two years. As ugly as at was, it was a good bike, and I felt insulted. So, I said ‘screw it’, and decided to take it under my wing and fix it up.”

By fixing it up, Derek was obviously not talking about restoring the CB650 with paint and some shiny chrome plating. When Derek began contemplating just what he’d do to the CB650 it was during the heyday of stuffing very fat rubber into the back ends of American-made v-twin motorcycles. On a bit of a lark, Derek wondered when someone would create a fat-tired sport bike. That line of thinking sent him off to do some research, and he became familiar with café racers. It was then he began to appreciate the 1960s and early 1970s period of custom ‘sport bike’ motorcycles – café racers. Derek’s plan was to take his old CB650, an unloved classic, and use the machine as a platform for his unusual vision of the café style.

First on his agenda was widening the original Comstar mag wheels. While unliked by some, Derek appreciates the five-spoke pattern of the Comstar wheel. Plus, some of his motorcycling friends told him widening a Comstar simply couldn’t be done. Wrong thing to say to Derek. “At the time, I really liked to go against the grain, and I don’t think anybody else was using Comstar wheels on their customs,” Derek says. “And then when people told me it couldn’t be done, well, it became a challenge to widen the Comstar rims.” A visit to local bike wrecker TJ’s Cycle yielded a second set of rims, a matching 19” front and a larger 18” rear as opposed to the stock 17”.

Derek cut the flanges off each side of the rear rim before rolling out two 3” x 3/16” flat aluminum strips. These hoops were then welded to each side of the rim, and the flanges welded back on, increasing the width from 2.5” to 8.5” to accept a 250 series rear tire. Easier said than done. Looking back on the project, Derek says widening the rims was the hardest part of the entire build – and that’s because the rim flanges are hollow, and not solid aluminum, making them very delicate to weld. His perseverance and dedication to building custom Comstar rims never flagged, but the CB650 project stalled after completing the widening chore.

After completing the wheels, Derek branched out to open Trillion Industries. While known for his aluminum welding repairs he also took on some serious one-off fabrication jobs, including constructing a helicopter and a frame-up custom v-twin motorcycle. As he focused on getting the business running, the CB650 sat from March 2005 to November 2006 before Derek got back to the build, completely stripping the CB650 down to the frame. To accommodate both the widened Comstar front rim and the beefy twin radial brake calipers Derek fit a complete – including handlebar and controls — 2003 Kawasak ZX636 inverted fork, machining new triple clamps from billet aluminum to expand the fork by 1.5”.

Fitting the 8.5” wide wheel in the rear involved Derek lopping off the chain adjusters from the original swingarm, using them to build a completely new unit extended by 2.75” and widened by 6”. “I bent and welded up the tubes, and definitely made up a swingarm that is far more robust than what that engine is ever going to put out,” Derek laughs. He widened the CB650’s frame on the left hand (chain) side and cut away all extra brackets.

Derek redid all of the frame welds after an old timer at a local bike show – where the frame in the rough was on display – said: “Kid, I don’t know about these welds,” Derek says. “I was worried for a minute until I saw he was pointing at a factory Honda weld!”

Giving the CB650 its café racer credibility is a fiberglass CR750 replica fuel tank and rear tail section, ordered from Airtech Streamlining in Vista, California. These pieces were for a CB750, but Derek cut them and re-glassed them to fit, and also frenched in the rear taillight. Up front a light sourced from the Harley-Davidson V-rod parts bin gave Derek the modern flair he was looking for, yet the lamp wasn’t so radical it no longer looked like a headlight. Bar end signal lights are pieces Derek made, and the rear units are Watson’s Designs LEDs, set into the swingarm near the lower mounts for the Kawasaki ZRX rear shocks.

Derek rebuilt the CB650 engine top to bottom, starting with new valves in the shaved head – something he did to slightly increase the compression ratio. New rings were fitted to the standard pistons and all new bearings and seals were used in the overhaul. The four carbs are stock 26mm Keihin piston valve units, but Derek has plans to upgrade to flat slide 26 mm instruments. He’s not after horsepower. “It’s a 30 year-old 650, why try to chase after the horsepower rabbit?” Derek says. “You couldn’t take it anywhere near what a modern 600 will do now.”

To get power from the narrow engine to the wide rear wheel Derek simply welded a 1.75” tube between two output sprockets, supporting the outer portion of the device in a bearing that’s actually caged to the frame. The foot pegs would be recognizable to riders of dirt bikes, as the Fastway stainless steel pads are from the world of motocross, and these are fitted to Derek’s own brackets and controls.

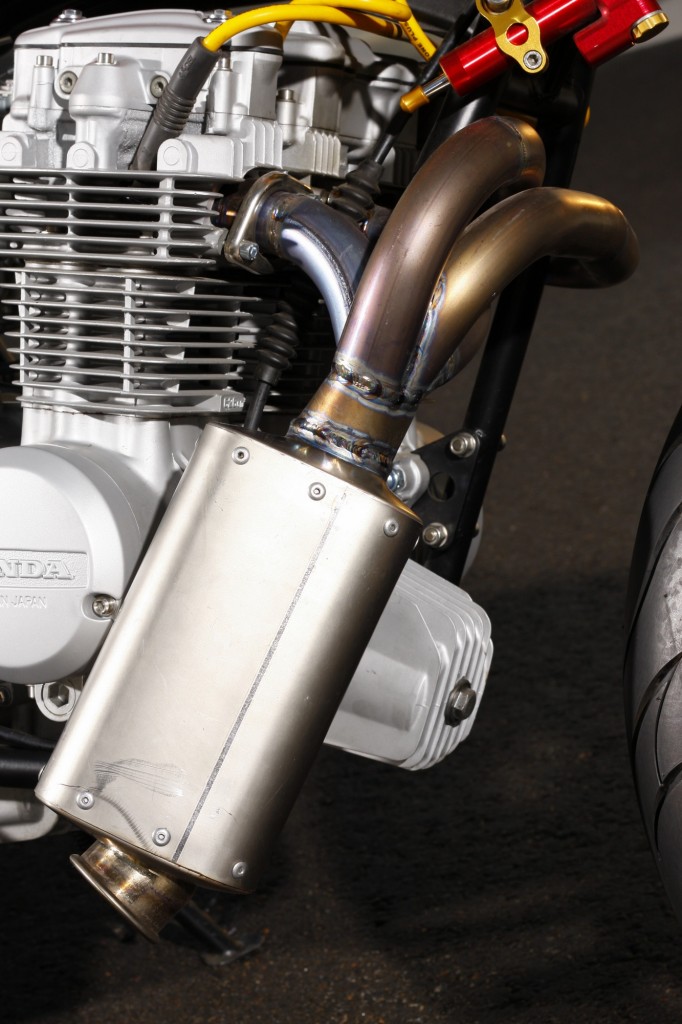

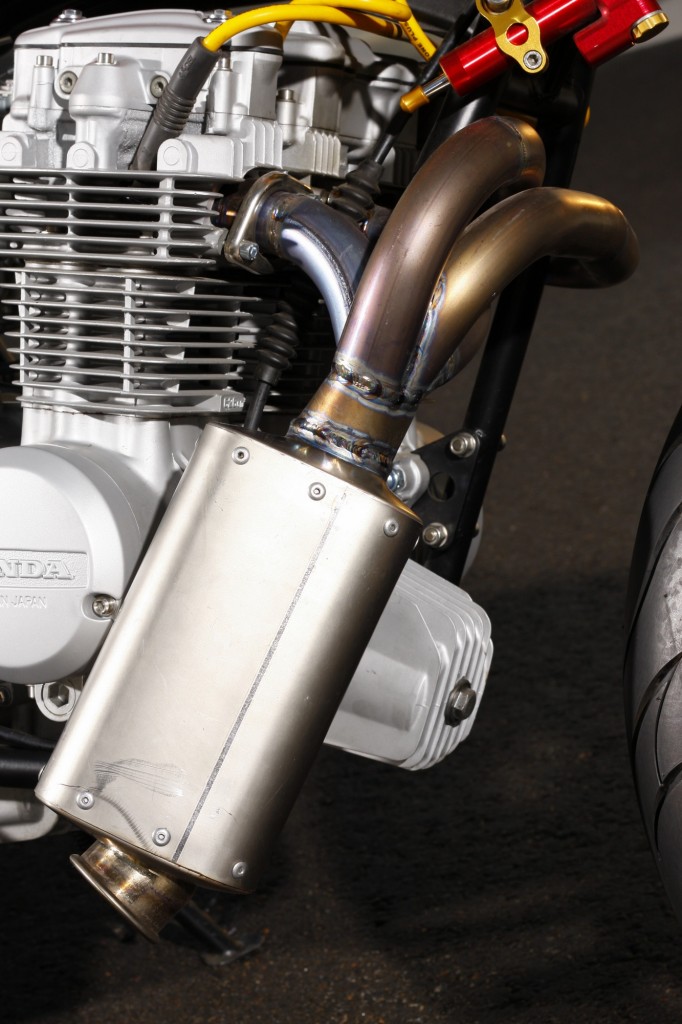

Now, that unusual exhaust. It’s made up of Suzuki GSX-R titanium headers that were being scrapped. Derek used as much of the tubing and fittings as he could, and manipulated them to dump into a Yoshimura canister. The bike is actually very quiet, and isn’t obnoxious at all when running. In homage to Honda racers of the 1960s, Derek’s friend Donny Klukas painted the machine red and striped it in yellow and silver.

“This is my interpretation of a modern café racer,” Derek says, and of his CB650 he adds: “I didn’t buy the project bike from Elvis. It was mainly because people made fun of my baby — people get attached to things, even ugly duckling motorcycles. I guess it became more of an exercise about what could be done to an unloved 30-year old motorcycle, and it just got carried away. It doesn’t make much more power than it did, and it wasn’t ever about the power, but more about the looks and how things can be transformed.”

Essentials:

Engine: 627cc SOHC, four stroke air-cooled inline 4 cylinder, 59.8 x 55.8 mm bore/stroke, est. about 55 hp @9000 RPM

Top Speed: yet to be determined

Carburetion: 4 Keihin piston valve 26 mm

Transmission: 5 speed constant mesh, chain drive

Electrics: CDI, 12V 9ah battery

Frame/Wheelbase: modified steel tube duplex frame, 56″ wheelbase

Suspension: ‘03 Kawasaki inverted front forks, lengthened swingarm (2.75”) and widened (6”), twin ‘04 Showa reservoir rear suspension shocks

Brakes: Dual 320mm radial disc front and 200mm single disc rear

Wheels/tires: original Comstars widened 3.50×19 front-120/70/19 Avon Cobra, 8.5”x18 rear- 250/40/18 Avon Cobra

Weight: 415 lbs. (189 kg) wet

Seat height: 34.0”

Fuel capacity: 4.0 gal. (15.1L)