Cross-Canada adventure in a freshly restored 1951 Ford

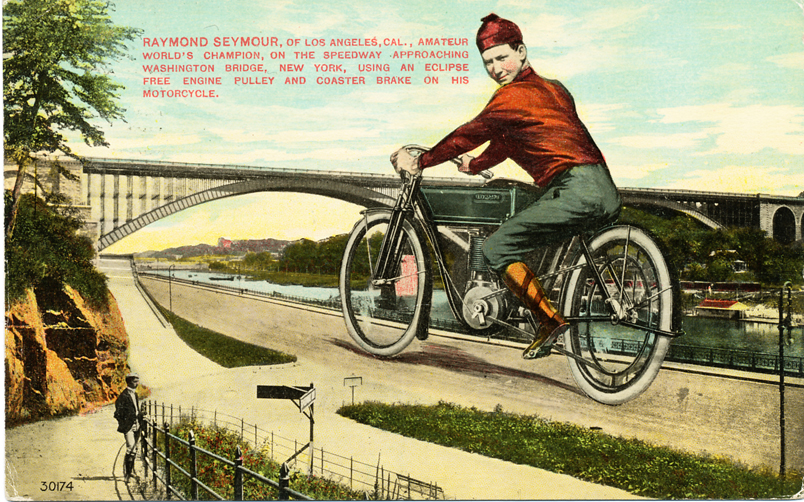

Bill Paul’s 1951 Ford at the first border sign, crossing from Alberta into Saskatchewan.

Story first published in the Calgary Herald Driving section. All photos courtesy Bill Paul. I took a particular interest in this story because Paul didn’t build his car to be a show-only specimen; he actually used the car as it was meant to be driven. No trailer queen this one.

Realizing a dream can take time.

Case in point: Calgarian Bill Paul and his 1951 Ford Two Door Custom – it took him more than 20 years to restore the car.

Completing the restoration was just the first part of the dream. In 2012 the semi-retired carpenter and his wife Vivian drove the Ford across Canada to their hometown of Brookfield, Nova Scotia. There, the Ford carried them in a parade that was part of the Coming Home to Brookfield festivities. Check that one off the bucket list.

In 1988 Paul bought the rusted-out car from a farmer near Langdon. At the time, he was renting a house in Calgary and had use of the garage.

“I’d become involved with the Nifty Fifty’s Ford Club in 1986 (that was the year the club got started), and I didn’t have an old Ford,” Paul recounts. “So, I went on the hunt and found this one.”

After taking the car to pieces, he spent a year or two working on various parts until the landlord sold the house. The next place he rented didn’t have a garage, so the project went to a property owned by a Nifty Fifty’s club member, where it was stored for the next few years.

As the couple moved from house to house the Ford sometimes went along, other times staying in storage. In 1993 when the Pauls bought a home in Riverbend and put up a garage the Ford came home for good.

“I began to putter with it a little more than I had before,” he says, and adds, “but it wasn’t until 2006 or 2007 that I really started to put my heart and soul into it.

“The guys in the club kept asking me if I was ever going to get the car together, and I thought, OK, enough fooling around.”

He had the body media blasted, and discovered more rust than expected, especially in the floor. Rusted metal was cut away, and new panels welded in – including floor, quarter and rocker panels.

Paul used a drill-mounted wire brush to clean up frame rails and applied a rust neutralizer before having the chassis painted black.

To lessen the pain on his pocketbook Paul would take two or three items a year, over the years, to be chrome plated.

“I did it piece by piece, a little at a time,” Paul says, “so I didn’t wind up with one big, expensive chrome plating bill.”

New nuts and bolts were used to put the car back together. Also new were many mechanical components, including brake drums, shoes and lines, shocks and front end parts.

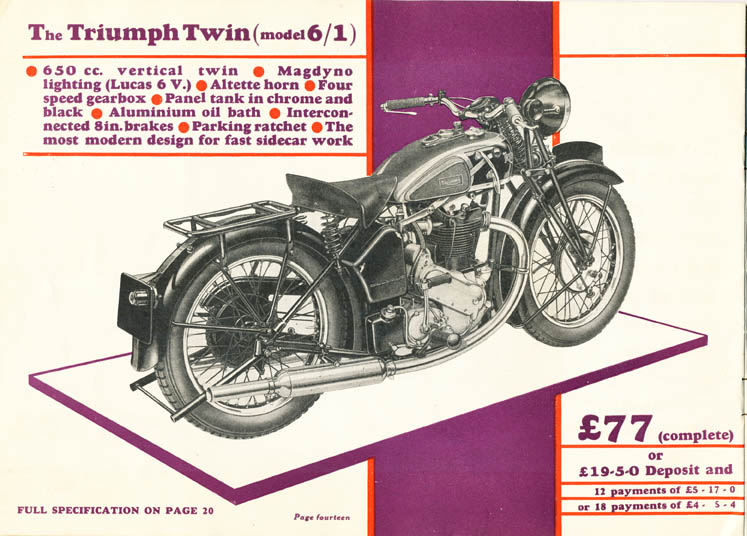

Paul restored the car to original specifications with the 6-volt electrical system. He kept drum brakes all around, the three-on-the-tree manual shift transmission and manual steering. He added some custom touches, including the Continental spare tire kit, sunvisor and dual exhaust.

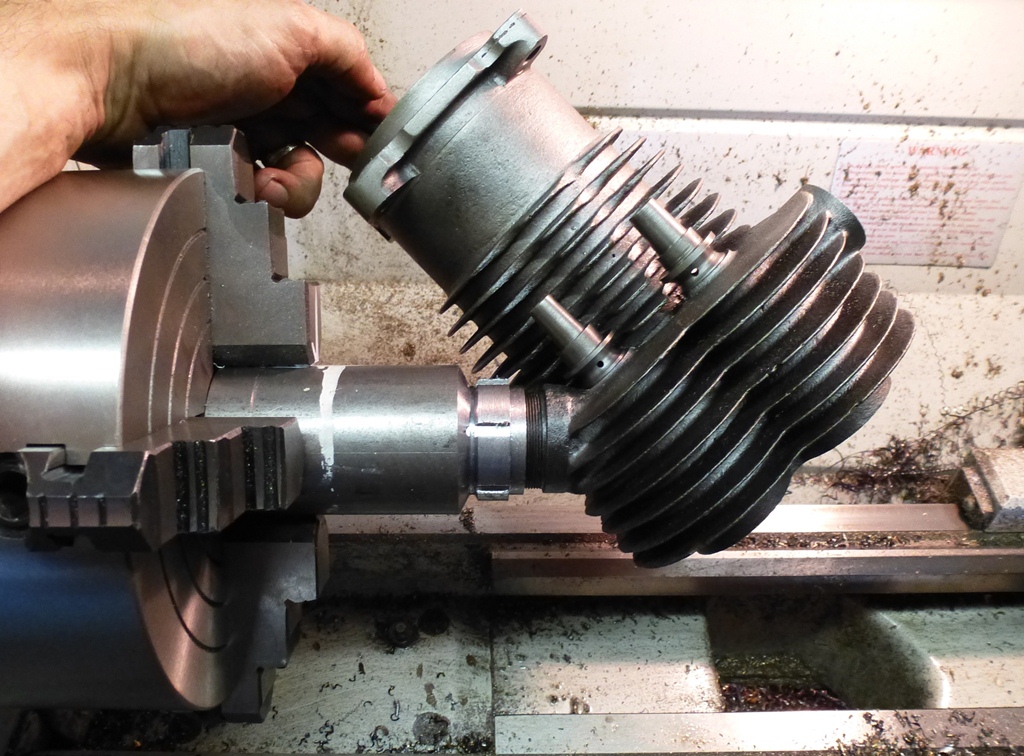

The engine in his car had a hole in the block, something he couldn’t see when he first bought the Ford. So Paul purchased a running 239 c.i. flathead Ford V-8 from a club member, and installed this engine in his finished car.

“It ran, but I thought it sounded noisy,” Paul says. “It had always been my intention to finish the car and drive it back home, and when I learned about the Brookfield homecoming, I bought a freshly rebuilt flathead and put it in the car.”

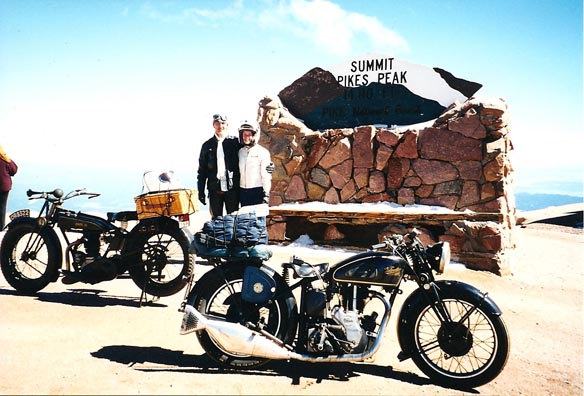

Ensuring the Ford was topped up with fluids, the Pauls left Calgary at 8 a.m. on July 14, 2012, and headed east on the Trans Canada.

“I probably had about 300 or 400 miles on it by then,” Paul says.

Crossing from Saskatchewan into Manitoba. The rebuilt flathead was running hot.

And that’s when the adventures began. In Saskatchewan Paul says he noticed the engine was starting to overheat, but it wasn’t until he was just outside Winnipeg that he really got concerned.

They made it to his brother in law’s house, and Paul spent some time locating a new radiator cap, which he replaced. But as they were leaving Winnipeg the driveshaft fell out of the car.

The rear yoke had a hairline fracture, and it had finally given up. At the Winnipeg garage there was nothing the mechanic could do without a replacement, so Paul phoned one of his Nifty Fifty’s friends.

“I have a bunch of parts stored there, and he got a yoke out and sent it overnight to Winnipeg,” Paul says.

Driveshaft back in the car, and now well into Ontario, the Ford began overheating again. Paul would periodically stop by the side of Lake Superior, fill a jug with lake water, and add it to the radiator.

From Manitoba into Ontario, driveshaft fixed, cooling problem getting worse.

In Sault St. Marie Paul located a new thermostat at NAPA, had it installed at the Firestone garage, and continued on.

“The car wasn’t boiling the water out, but we were just losing water,” he says. He continued to stop, topping off the radiator, for the rest of the journey.

Stopped by the marker denoting entry into Quebec.

The Pauls arrived in Nova Scotia on July 20 at 8:45 p.m., the night before the day of the parade, with a car that was overheating. Insult to injury, the generator had also quit.

Paul figured they’d come too far to miss the parade.

He phoned a few of his Nova Scotia car friends that evening, and at 8 a.m. Saturday morning a replacement generator had been found and borrowed. Paul got it in the car and narrowly made the 10:30 parade lineup, with five minutes to spare.

The Ford made it through the parade, and Paul then spent several days pulling off the heads to track down the overheating issue. One head was bowed, and after it was planed Paul noticed it was also cracked.

A replacement head was located in Truro, and it was planed and installed. The generator and starter were rebuilt at Al Roland Auto Electric in Truro, and Barry Weatherby, also of Truro, tuned up the car and gave it a once over. He noticed the front-end alignment was out some 20mm.

Entering New Brunswick (above) before finally arriving in Nova Scotia (below) at 8:45 in the evening, car overheating and now not generating current.

“I didn’t think the car had been handling that well, but it had been professionally aligned before we left Calgary,” Paul explains.

They left Nova Scotia on Aug. 14 for the return trip, and made it into northern Ontario when a valve guide clip let go, leaving the valve useless. There was no cell phone service, so Paul decided to nurse the car into Winnipeg.

With the mangled clip removed and replaced with one sourced from a Winnipeg flathead enthusiast, the Pauls were back on their way to Calgary.

The rest of the trip was uneventful, but the car was still overheating after 10,621 kilometres.

Paul has since had replacement heads inspected for cracks and planed flat. With new gaskets, he hopes the overheating issue will be a thing of the past.

Here’s hoping the completion of his next dream, the restoration of a 1956 Ford convertible, will be finished soon.