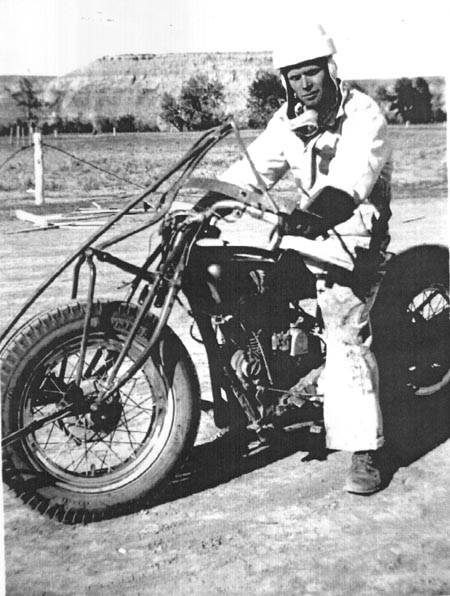

photo courtesy John Dean: Walt Healy at speed aboard Cannonball, his flat tracking Indian. Photo taken at O’Keefe Ranch, Vernon, B.C., circa 1996.

Walt Healy was a character. There’s no other way of describing this Calgary motorcycle retailer. I had the opportunity to chat with Walt on several occasions, and we sat down for a lengthy interview late in 1996. The article that appears below was published in the now-defunct Indian Motorcycle Illustrated magazine from TAM Communications.

Walt died in January, 2002, after attending a Canadian Vintage Motorcycle Group dinner. After regaling us all with motorcycling tales and sharing plenty of laughter he left the building and got into the passenger seat of his car. His companion, Shirley Alex, went around to the driver’s seat. By the time she had opened her door, Walt had stopped breathing. He died with his boots on, and had essentially taken part in his own send-off party. If we could all have such a wonderful departure!

photo from the author’s collection: Walt Healy (right) at the gates of Banff National Park, with an Indian Chief and sidecar.

INDIAN LEGENDS

Just as the famous Indian Motocycle Chief became a legend in its own time, so has Calgary, Alberta’s Walt Healy. Founder of the still flourishing Walt Healy Motorcycles in 1931, he has been a Canadian institution in the motorcycle industry for 65 years.

Walt, an affable, bearded gentleman 83 years young, recently recounted some of his Canadian Indian Motocycle legends.

LEGEND OF THE DELIVERY BOY

Walt was a young boy when his ‘love affair’ with the motorcycle began.

“I used to walk past Morris Greenhouses on my way to Hillhurst school,” Walt says. “There was an old Indian Power Plus leaning against a fence at the greenhouse, and every time I walked by I’d say ‘One of these days I’m going to get a motorcycle.'”

He was 13 years old when he started pedaling a bicycle to deliver parts for Calgary’s Diamond Motors, a job which earned him enough money to buy a much yearned for 1914 Douglas motorcycle.

Purchased for $15, the Douglas helped him deliver faster and increased his income. He increased his income further by giving neighborhood kids instructions on how to ride a cycle. For five cents he’d let them take it down the street. “But if they went around the block, out of my sight, it was ten cents!”

In the winter of 1929 a tip from a friend led him to get a job delivering groceries for the Piggly-Wiggly. So, for $16.50 a week, Walt went to work delivering sacks of potatoes and 100 lb bags of flour. This job was short lived, as the Piggly-Wiggly was amalgamated with a larger grocery chain.

“So I just started on my own. I’d pick up and deliver for Marshall Wells, Alberta Paint, anybody. I’d get anywhere from 10 cents to 25 cents a load,” Walt recalls. Thus, Walt’s Service was created, a forerunner of the modern courier.

Walt was running a 1918 Harley Davidson paired up with a National sidecar. When found, the Harley’s crank was gone and the rods were worn, but Walt fixed it himself by machining new bushings for the rods.

But it was the Indian 101 Scout with a sidecar that became the basis for the legend of Walt Healy.

Walt thought nothing of moving an upright piano up 10th Street hill with the 101 and a sidecar. Or, delivering 4 by 8 foot panes of glass, perched between the cycle and the chair. With his right hand holding the glass upright, and his left on the throttle, Walt would be off. This feat was made easier due to the left hand throttle unique to Indian motorcycles.

Long-time resident Dave Wilson can remember the image of Walt racing along Calgary’s unpaved streets.

“I recall seeing Walt careening in a cloud of dust up 10th Street hill, or along a downtown street. Walt and that Indian were an institution!” Dave says.

LEGEND OF THE HARLEY CHALLENGE

A snub from the local 1920’s Harley-Davidson dealer was instrumental in prompting Walt to become the traditional competition as the owner of an Indian Motocycle dealership. Let’s step back a few years, to a scene which occurred in that Harley-Davidson shop.

Walt was running his delivery service using the Harley and the Indian 101 Scout, both sidecar outfits. When the time came to purchase new rigs, he went to Clyde Paul, the Harley dealer.

“I put a $20 deposit on the next police outfit to come in. But we had a little problem with trust,” Walt says.

It seemed Clyde had a different idea about how to run a business. When Walt came in to pay the balance and pick up the police rig, he was simply told that it had been sold elsewhere.

Walt, a trusting youth, gave Clyde another chance. Again, he was promised the next outfit to come into the shop.

When Walt went in to pick up the rig, Clyde told him he wasn’t going to sell, he was turning it into a hill climber for himself.

Thoroughly disgusted, Walt told him the Indian 101 Scout motor on the work bench would suffice for his $20 investment in futility. This may have seemed small consolation, but Walt knew where the motor belonged. He picked up the rest of the Indian from a friend for another $10.

Having revenge as his motive, Walt turned that $30 Indian 101 into a Harley eating hill climbing monster.

“I built it so I could go out and kick his ass! I built that bike for no other reason,” Walt enthuses. Every climb that Clyde entered, Walt entered. And Walt whipped him.

And as Walt remembers that long-ago scene in Clyde’s shop, it is evident he took its lesson to heart. “If you put a deposit on something, that’s yours. Even today, that’s my philosophy, you simply don’t break that trust,” Walt says, hitting the table top for emphasis.

LEGEND OF THE TAKEOVER

Displeased with the service provided (or not provided) by Clyde Paul, in August, 1931, Walt went to the local Indian dealer and explained he needed two motorcycles. The Indian dealer at the time said, “Come up with $100, and I’ll sell you all my stock. There’s enough here to build two Indians, and we’ll write to Springfield and tell them you’re the new Calgary Indian Motocycle dealer.”

Walt, who was 18 years old, had a friend who worked for the Canadian Pacific Railroad co-sign a $100 note for him. He bought the dealer’s stock, and set up shop. He used a neighborhood garage to fix motorcycles, and kept his stash of parts behind a chesterfield in his living room.

“I couldn’t have survived on just the Indian dealership, though,” Walt recalls. “The delivery business supported the early days of the shop.”

Walt moved his Indian Motorcycles Sales and Service from the garage to 142 10th Street, into the old Union Building. For $20 a month, he rented the 18 foot by 30 foot shop, and built a kitchen and a bedroom in the basement.

Word of mouth helps build a business, and the word around town was that Walt and his father Robert, whom he hired as a mechanic, knew their Indian’s. Service work kept Walt busy, and even a stint in the Army from 1942-1945 couldn’t keep him away from the business. He’d sneak off the base at night, fix Indians at his shop, and return to the base in the early hours of the morning. An unexpected backfire from his motorcycle while returning to the base one morning gave Walt away, and got him in no end of trouble. But that didn’t daunt Walt; he just carried on.

photo from the author’s collection: Walt Healy Indian Motorcycle Sales and Service, his shop at 142 10th St. in Kensington, Calgary.

After 15 years at 142 10th Street, construction began in January of 1946 on Walt’s new shop across 10th Street. Walt’s cousin owned a saw mill in Caroline, Alberta, and for $600 delivered the lumber to put up the new building. With a few additions, Walt Healy Motorcycles stayed at 227 10th Street until 1993, and then moved to a northeast Calgary industrial area at 4520 12 Street N.E.

As a boy, Ken Harris, an Indian restorer and avid motorcyclist, can remember making trips down to Walt’s shop on 10th Street and staring in the window. “Walt’s shop was, and still is, magic to me!”

LEGEND OF THE MAN

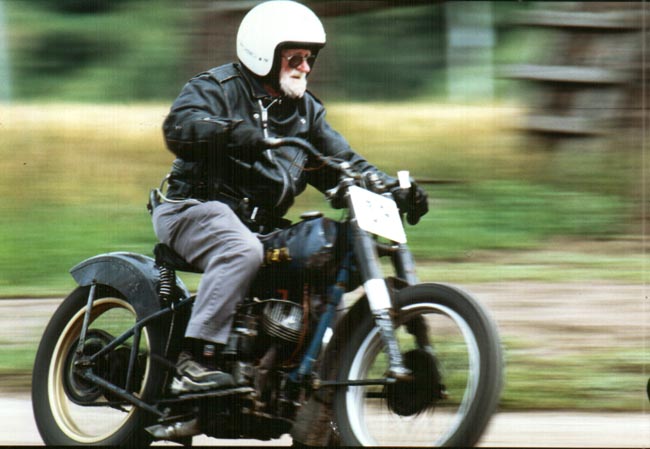

The business is not the only pleasure Walt gets from motorcycling. Walt doesn’t keep track of his miles, but he figures more than a million miles have rolled beneath him. The amazing thing is, that’s just over the past 10 years. Having been mounted on two wheels since the late 1920’s, Walt has been riding for eight decades.

For many of those decades, Walt used Indian motorcycles for both work and pleasure. He once toured the same 1935 Chief and sidecar outfit he used for deliveries to Las Vegas, and from there to Los Angeles in the early 1940s. While on that tour he met and formed a friendship with Floyd Clymer, the famous American author of motorcycle manuals and other cycling ventures.

The basement of Walt’s home is filled with hill climbing and racing trophies. Calgary motorcyclists once had a choice of four hills on which to race, but all that remains of the legendary sport are ruts carved into the face of Tom Campbell’s Hill and three other hills near the city. Walt’s list of races he’s taken part in with his old AMA registered number 38 on an Indian motorcycle includes Daytona Beach.

Walt remembers traveling to a 1937 hill climb in Spokane, Washington. One other hill climber, commenting on Walt’s $30 Indian Scout 101, told him to throw a blanket over the machine.

“I said ‘Never mind how ugly you think the bike is, that thing will climb hills!’ And I won their hill climb in the class I was in. They even put me in several other classes, and I came in second racing against the hot rod OHV fuel burners!” Walt enthuses.

Motorcycle stunts of all kinds were always up the sleeve of Walt’s motorcycle jacket. Whether it was steering his cycle with his feet while rolling a cigarette or performing his flaming board wall crash, Walt’s been crazy enough to try it all. He even performed his board wall stunt in 1995 at the O’Keefe Ranch Vintage Motorcycle Show using the old hill climbing Indian.

photo from the author’s collection: Walt Healy on his boardwall crash machine; bars on the front help break through the wall.

As a founding member of the Calgary Motorcycle Club in 1926, and the Ace-Hy Motorcycle Club in 1938, Walt has been instrumental and legendary in promoting the sport of motorcycling. For 18 years and four ministers of transport he sought to make motorcycle mechanics recognized as a licenced trade in Alberta. Walt was finally successful in 1986, when he finally received his own motorcycle mechanics licence. Walt created a ‘Learn to Ride’ program years ago which became the Calgary Safety Council, and that extended to what is now known as the Canada Safety Council.

Walt may have struggled to keep his business alive in the early years, but failing was never an option. He was told in 1931 by the local Harley-Davidson dealer he’d last only six months. “After 65 years, I guess I’ve shown him!” Walt laughs.

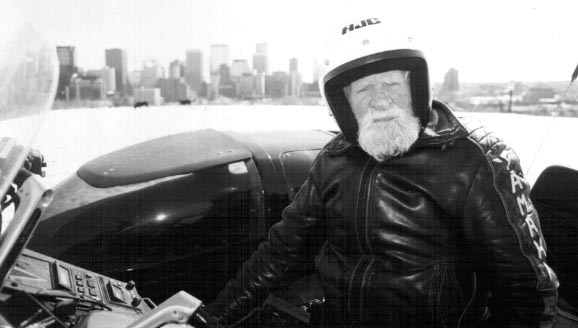

photo by the author: Overlooking Calgary, Walt Healy with his Yamaha Venture and sidecar.

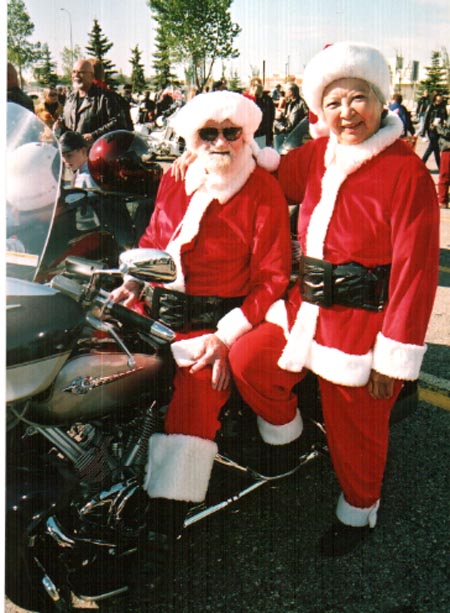

photo by the author: Walt Healy and Shirley Alex at the start of the Salvation Army Toy Run, Calgary, circa 1998.