Back in early 2011 I was assigned to write a story about a Sportster for American Iron Magazine. I got a name and a phone number.

The builder’s name was Joe Cooper of Cooper Smithing Co., and we had a great conversation about bike-building and metal-shaping. Joe’s attitude was refreshing, and he was clearly a talented craftsman. Along with many other pieces he created for the Sportster, he hand formed the rear fender and the gas tank — it’s clear he was honing his skills.

Today, Joe is turning out some very high-quality hand-crafted Made in America fenders, and I wouldn’t be surprised to see them on many new custom builds.

Thought I’d take this opportunity to post up the AIM story. Take a look at Joe’s newly-launched website, and watch the video. An artisan at work.

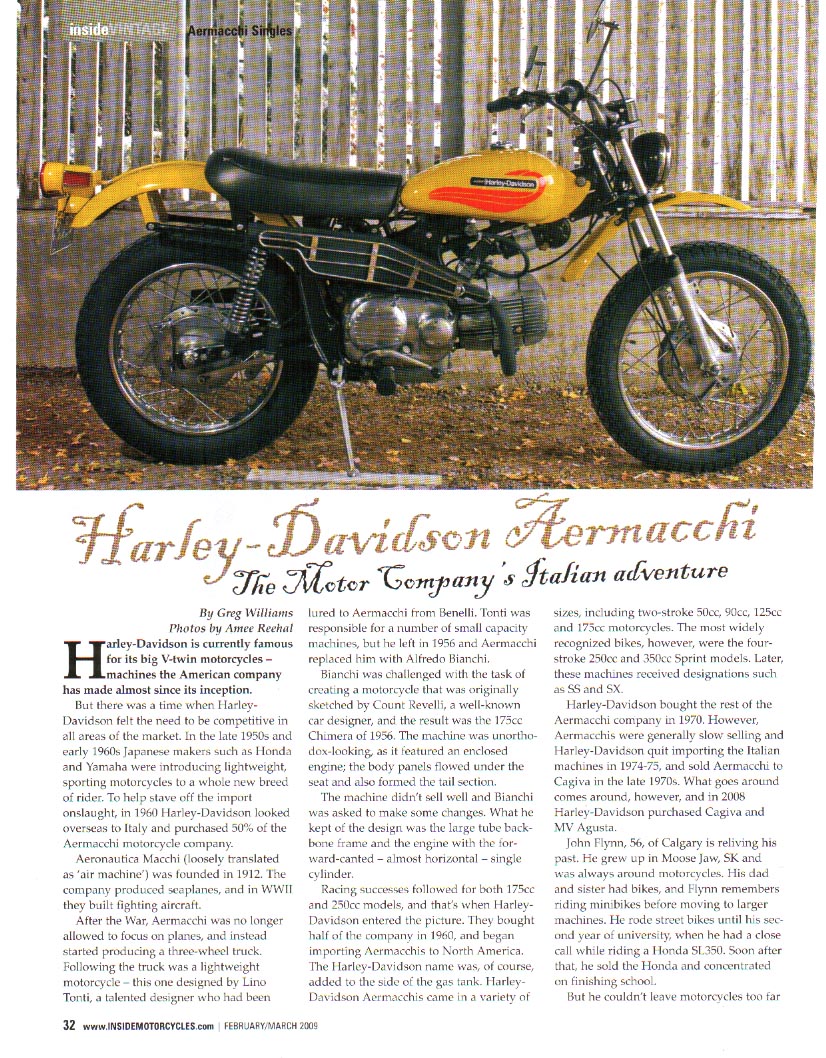

Joe Cooper’s custom 1999 Sportster belongs to Scott Weinmann, photo courtesy Joe Cooper.

The most important tools at Joe Cooper’s disposal are his hands.

With them, he has built other tools, ones necessary to fabricate exquisitely detailed motorcycles. But even those other tools are simple. Take the hollowed out stump he uses as a sheet metal form.

In this humble piece of wood, a remnant of a tree felled on his Pacific Northwest property, Joe hammered out both the fuel tank and the rear fender seen on this featured 1999 Harley-Davidson XL.

“I had a half-hollowed out stump, a piece of sheet metal, and a hammer to smack it with,” Joe says of his process. All of the forming occurred in that stump, and Joe simply smoothed up the metal pieces later with a planishing hammer and an English wheel – tools he again built for himself.

Joe was born and raised in one of the smallest towns in Oregon, with just one paved road leading out of it. When he was young the thought of hitting that one road out of Crane, Oregon aboard a motorcycle appealed to his rebellious nature. Plus, motorcycles are machines that, as he puts it, only take a twist of the throttle to make the world behind you disappear.

And that’s what he did. His motorcycle took him to Seattle, where he learned to TIG weld while making airplane components. Still in Seattle Joe found himself working in a custom motorcycle shop, where he lent his hand to over a dozen builds. More interested in t-shirts than motorcycles, though, the business was in jeopardy.

It was then that he took control of his future, and set out on his own to open Cooper Smithing Co., a home based shop in Buckley, Washington dedicated to nothing but metal fabrication. While working on several smaller projects Joe began his first full bike build under Cooper Smithing Co. when a blacksmith friend donated a wrecked 1999 Harley-Davidson Sportster. “He said, ‘Here, why don’t you try to make something out of this bike’,” Joe recalls.

Starting with the damaged and bent frame, Joe cut away all of the Harley-Davidson tubes, leaving just the engine in the factory cradle. Next, Joe found a use for the 16” Harley rims he had been given in part trade for some of his metal work. These rims were laced up to the original Sportster hubs, and Coker reproduction Firestone tires fitted.

Joe placed the wheels and the engine on his frame-building table, a stout piece of equipment he bought as surplus from a Boeing airplane factory. With its 4’ by 8’ almost perfectly flat steel top and holes drilled every 6”, the table turned out to be the ideal platform for his frame jig.

Using his lathe Joe machined up a neck, and proceeded to bend and weld tubes around the engine and wheels. “I connected the dots,” he says. The rigid rear features 3/8” axle dropouts that Joe machined and fit into notches in the chainstays, the tubes of which are also internally gusseted. “They’re not just a plate welded to the tubes,” Joe says, and adds that it was important to him to make the chassis as strong as he possibly could.

Joe next turned his attention to the fork, an item he created using beefy, gusseted tubes and forgings built by his blacksmith friend who had donated the Harley. Atop the springer fork is a handlebar Joe created, and a Korean War-era signal lamp was repurposed to function as a headlight. Hand forged by Joe, the single headlight mount was bent to match the line of the handlebar, an item that is adorned with Sportster hand controls.

In fact, several other pieces of the donor Sportster were implemented. While he could have built one-off parts such as foot controls, Joe says the bike didn’t seem to want them. The slightly worn rubber footpeg rubbers suited the organic feel of the custom. Joe also used the Sportster’s brakes, mounting the front caliper to a custom made bracket.

Joe fashioned a metal seat pan, over which he slipped and stitched an old leather cover from another saddle he had in the shop. While Joe crafted the fuel tank and rear fender using the tree stump, the oil tank is an old helicopter engine cylinder. With its cast fins, the cylinder based oil tank was mounted in front of the engine where it would hit the majority of cooling air.

When it came time to rebuild the engine Joe tore down the powerplant and checked the Harley-Davidson manual to insure all of the tolerances were within spec. There weren’t many miles on the mill, as all that was required was a light hone to the cylinders. But all bearings, seals, gaskets and rings were replaced before the unit came back together, topped off with heads that only needed the valves lapped and the carbon deposits removed.

The stock carb was left in place and the air filter cover is the sump cover from a Yamaha XS850. A two-into-one header ends with another remnant of a Boeing surplus auction, this a hollowed out cable spool for an airplane wing flap.

Finishes are simple, too. The frame and the back legs of the fork are painted black, while many other objects, including the front fork legs, handlebar, headlight mount, oil tank and sprocket cover are copper plated. Wheel rims were the only parts treated to powder coating. The gas tank, rear fender, headlight and exhaust are nickel plated, and that led the bike to be nicknamed The Jefferson, as that’s the president on our American nickel.

Joe says he didn’t build The Jefferson as a show bike, but after completing the machine he did truck it out to the 2010 AMD World Championship in Sturgis. Here, he entered the motorcycle in the modified stock class, and returned home with a second place trophy. Since then, The Jefferson has been sold to Scott Weinmann of Ateliers Velocette, a New York based high-end motorcycle rental company, where machines can either be used for riding, or in a movie or fashion shoot.

If anyone rents The Jefferson to ride, Joe says: “They’ll have a hard time riding around on it without a smile on their face – it’s got an old-timey feel to it, and it sounds great.”

Here are the build details:

Owner: Scott Weinmann

Builder: Joe Cooper, Cooper Smithing Co., Buckley, WA

Year/model: 1999 Harley-Davidson XL

Time to build: 5 weeks

Chromer: American Plating, Centralia, WA

Polisher: American Plating

Powder coater: Kens Powder Coating – Spanaway, WA

Painter: None

Color: black and nickel

ENGINE/TRANSMISSION

Engine, year/model: 1999 XL

Builder: Harley-Davidson

Displacement: 74”

Horsepower: stock

Cases: stock

Flywheels (make & stroke): stock

Balancing: stock

Connecting rods: stock

Cylinders (make & bore): stock

Pistons (make & comp. ratio): stock

Heads: stock

Cam (make & lift): stock

Valves: stock

Rockers: stock

Lifters: stock

Pushrods: stock

Carb: stock

Air cleaner: Cooper Smithing Co.

Exhaust: Cooper Smithing Co.

Ignition: stock

Coils: stock

Wires: stock

Charging system: stock

Regulator: stock

Oil pump: stock

Cam cover: stock

Primary cover: stock

Transmission, year/model: 1999 XL

Case: stock

Gears: stock

Mods: stock

Clutch: stock

Primary drive (belt/chain): stock

Final drive (sprocket/pulley manufacturer): stock

CHASSIS

Frame (year, model): 2010 Cooper Smithing Co.

Rake: 34°

Stretch: stock

Front forks: Cooper Smithing Co.

Mods:

Swingarm: rigid

Front wheel (size and make): XL hub w/16-3” rim

Rear wheel (size and make): XL hub w/16-3” rim

Front brake (make/# piston caliper): stock

Rear brake (make/# piston caliper): stock

Front tire (size and make): Coker/Firestone 500-16”

Rear tire (size and make): Coker/Firestone 500-16”

Front fender: N/A

Rear fender: Cooper Smithing Co.

Fender struts: N/A

ACCESSORIES

Headlight: Korean War era signal light

Taillight: Cooper Smithing Co.

Fuel tank: Cooper Smithing Co.

Oil tank: Cooper Smithing Co.

Handlebars: Cooper Smithing Co.

Risers: Cooper Smithing Co.

Seat: Cooper Smithing Co.

Pegs: stock

Chain guard: Cooper Smithing Co.

Speedo: N/A

Dash: N/A

License bracket: Cooper Smithing Co.

Mirrors: N/A

Hand controls: stock

Foot controls: stock

Levers: stock

“The Cross Bones is an interesting looking motorcycle,” Crump says of his initial reaction to the ‘bobbed’ styling. “With the spring fork out front and the sprung solo seat, it looks like an old-school bike. From an uneducated point of view, you probably couldn’t tell if it was old or new.”

“The Cross Bones is an interesting looking motorcycle,” Crump says of his initial reaction to the ‘bobbed’ styling. “With the spring fork out front and the sprung solo seat, it looks like an old-school bike. From an uneducated point of view, you probably couldn’t tell if it was old or new.”