Dermot Walshe — Motorcycle Illustrator

Here’s a column that first appeared on the pages of Cycle Canada about four years ago — still one of my favourites. It’s a reminder that motorcycles, and the passion for them, transcends the metal. Dermot Walshe continues to draw, mostly kids cartoons, but he has plans for a motorcycle feature in the future. Enjoy!

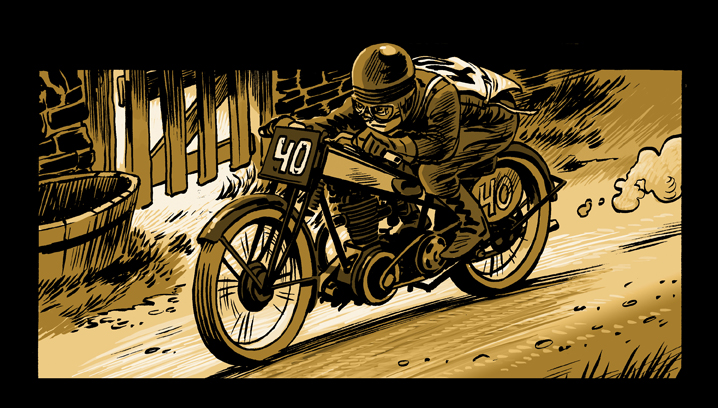

Image courtesy of Dermot Walshe.

With a stroke of his pen Dermot Walshe dramatically moves a motorcycle from the road or the racetrack to the printed page.

Walshe, of Oakville, Ontario is a man of talent. Armed with a pencil, pen and ink, and a computer he creates amazing images. Just have a look at the accompanying panel drawn by Walshe of Stanley Woods on a Cotton motorcycle circa 1922 racing in his first Isle of Man TT. It’s perfect.

Born in 1962 in Toronto, Walshe vividly remembers the first time he ever saw a motorcycle. He grew up on the outskirts of the city, and from a small stand at the side of the highway he would sell rhubarb to passing motorists. One afternoon, Walshe heard thunder. He looked up to the sky, and there wasn’t a cloud. Then, a big Harley-Davidson roared by, and another, followed by a B.S.A., and more – likely all big American v-twins and British iron. To young Walshe, the procession seemed to last half an hour. In all likelihood, it was less than a minute or two. But the sight of that passing gang was seared in his memory.

Not long after Walshe determined he would get some money together and buy a bike. But that didn’t happen until his first year of university, when he dropped out of landscape architecture and bought a used Yamaha SR185. Walshe said he bummed around Toronto on this single-cylinder machine with push-button starting, and he crashed it quite a few times before he needed a replacement.

From that point, Walshe’s motorcycling career has been nothing short of interesting. Between 1989 and 1995 he raced vintage machines including a Yamaha SRX600 and a Honda CB350, and said some fast laps at Mosport and drafting at Daytona were among the highlights. He’s traveled by scooter around Indonesia, and by his count has bought, sold, ridden – or destroyed – more than 50 motorcycles such as a Norton 850 Commando, a Ducati 860 GT and a 1950 B.S.A. Gold Star. Aesthetically, pre-War motorcycles with a rigid frame and a girder fork are his favourites, although he just bought himself a 1977 Yamaha XS650.

As for art, Walshe was always handy with a pencil and paper. He’d sketch and doodle and draw comic strips, and planned to do something creative with his life. Landscape architecture wasn’t it. While in that program, however, he met another student who commented on his drawing talent, and told him he should be in animation. Animation? He got a big shock when he learned what that was.

“That’s when I had my first inkling that animated cartoons were actually manufactured,” Walshe said. “I never really thought that you didn’t take a camera to cartoon land. I was kind of naive that way.” He attended an animation program at Sheridan College but never finished. Eventually, Walshe put his not insignificant talents to commercial use as a storyboard artist –someone who must quickly and accurately draw out the scenes of a movie, television show or commercial. He’s worked for the likes of Disney on films such as Mulan, Return to Neverland and Little Mermaid 2. For most of the last decade he’s worked on a freelance basis (click here to see samples).

During periods of downtime Walshe likes to dabble with projects that are of interest to him. Such a project is the tale of 17-year old Irishman Stanley Woods, who struggled in 1922 against factory teams and experienced riders to finish in fifth place aboard a Cotton motorcycle during his first Isle of Man TT race.

“Stanley Woods inspires me,” Walshe said. “He had a lot of audacity and he refused to give up. He was a gentleman racer who played fair but took advantage of everything he could.” Woods, in fact, had raced his father’s Harley-Davidson before deciding he could take on the TT. He wrote to most major British motorcycle manufacturers, requesting a ride, and it was Cotton who took on the youngster. His creative requests helped him land the Cotton, but nothing was going to come easily. During his 1922 outing on the 350cc Cotton, just about everything that could go wrong, did. He botched the start, having to stop to retrieve some fallen spark plugs. The machine caught fire in the pits. Not long after putting out the flames and back on the circuit, Woods had to stop and wrestle with the valves thanks to a broken push rod.

Recently, Walshe drew up eight pages of Woods’ story, keeping his eye on the clock to determine how long it might take him to produce a 100-plus page graphic novel, or even an animated film. For now, it’s simply an idea that’s percolating. Walshe ideally needs someone to write a cheque before he could spend a year on such a project, but it’s one that’s dear to him.

“Most motorcycle content (currently being drawn) is about booze and babes,” Walshe said. “But I think there’s more to the story of motorcycling than that.”