Ariel Square Four in retrospect

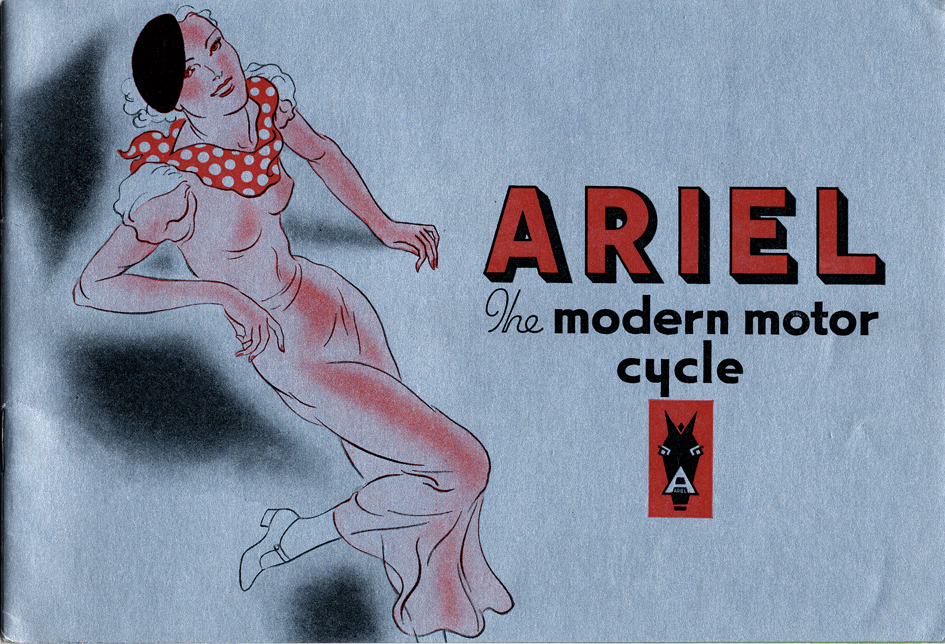

This column first appeared in The Antique Motorcycle magazine, the newsletter of the Antique Motorcycle Club of America. What follows is a discussion of the Ariel Square Four motorcycle with information gleaned from a collection of period brochures. Let’s begin at the beginning.

Ariel got its start in 1869 when James Starley, an engineer with the Coventry Sewing Machine Company of Birmingham, England, thought two-wheeled transportation held some promise. In 1870 together with his partner William Hillman the pair built their first Ariel high-wheel bicycle, and selected the name of their company based on a flying spirit from Shakespeare’s play The Tempest.

Those two founders could not have imagined the Ariel name would, some 60 years later, become associated with a four-cylinder motorcycle that defied conventions of the day. In the earlier column I introduced the Ariel Square Four, however this time I’d like to investigate the model more fully, focusing narrowly on its 1931 to 1959 production run.

Ariel wasn’t the first to market with a four-cylinder motorcycle. Early North American makers of fours include Ace, Cleveland, Gerhart, Henderson, Indian, Militaire and Pierce. Each of these ran an inline-four cylinder powerplant, meaning the engine was placed longitudinally in the frame. There were also several other makers of fours, and European creators were FN (I-four) and Nimbus, also an inline four.

Aside from Ariel in Britain there was Brough-Superior (flat-four), Matchless (V-four), Vauxhall (I-four), Wilkinson (I-four) and Wooler (flat-four). Of all the British concerns, only Ariel’s Square Four met with any real success. The Brough-Superior four was a prototype machine that never entered production, and Matchless built its expensive V-four, the Silver Hawk, in limited numbers only between 1931 and 1935.

Indian quit four-cylinder production in 1942, and apart from Ariel’s Square Four no other maker built a four in full-scale production until Honda rewrote the books in 1969 with the CB750 multi.

Forty years earlier, in 1929 Ariel’s Charles Sangster employed Edward Turner, who was hired expressly for his ideas about four-cylinder engine construction. Previously, Turner managed a motorcycle shop in Peckham, England, and had built a single-cylinder motorcycle engine while working there. However, he’d drawn plans for an engine that held four pistons in a square layout, with fore and aft crankshafts geared together.

According to Roy Bacon in his book, Ariel: The Postwar Years, the square four layout “…offered the same good balance as the in-line (four-cylinder engine) plus very compact dimensions, while the four small even power pulses of the cylinders was far less destructive than the one thump of a single.”“As originally schemed by Turner,” Bacon wrote, “the Square 4 engine was undoubtedly light and compact, being made more so by the use of a three-speed gearbox built in unit with the engine. He coupled the two crankshafts together by cutting gear teeth on the central flywheel each had, and the rear one drove the gearbox. So small and light was the assembly that it could, and did, fit into the 250 frame (Ariel’s 250cc Colt that was fitted with a forward-canted cylinder and head, which fit between widely splayed front frame downtubes) giving a very light motorcycle.”

However, what finally entered production wasn’t Turner’s initial vision. Inadequate cylinder head finning resulted in cooling problems, and the unit-construction layout, Bacon notes, would have been too costly for full-scale production. Ariel instead built a 498cc four-cylinder engine with chain-driven overhead camshaft and separate gearbox. The four’s crankcase fit neatly between the splayed downtubes of the firm’s 500cc sloper rigid frame, which meant something of a weight penalty. Ancillary components, including fuel tank, girder fork, wheels and brakes were shared between the two models. Shown on the stand late in 1930 at the Olympia Motorcycle show in London was the brand new Square Four for the 1931 model year.

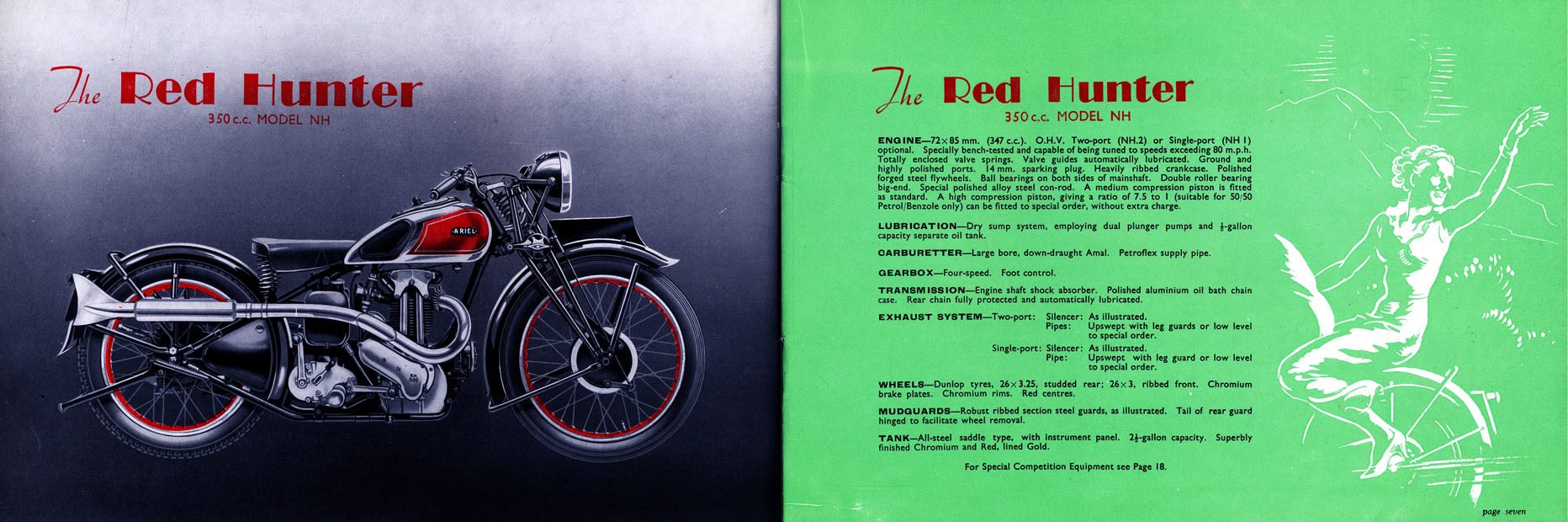

The Square Four met with some early success, including placing first in the London to Land’s End Trial, but to give better sidecar-hauling capability in 1932 capacity was increased to 601cc. Ariel sold both the 500 and 600 Square Fours until 1933, when only the 600 was available for purchase. The earliest Ariel brochure I have in my collection is an incomplete 1935 edition, which is missing the specification page for the Square Four.

On an introductory page, though, Ariel’s text states: “The Power Unit of the SQUARE FOUR. Tested and found well-nigh perfect by thousands of satisfied owners, the most successful multi-cylinder Motor Cycle of all time remains, except for detail improvements, unchanged for 1935. On the Square Four you can tour in silence or you can indulge in road speed in excess of 80 m.p.h., with complete absence of vibration or noise at all engine speeds.”

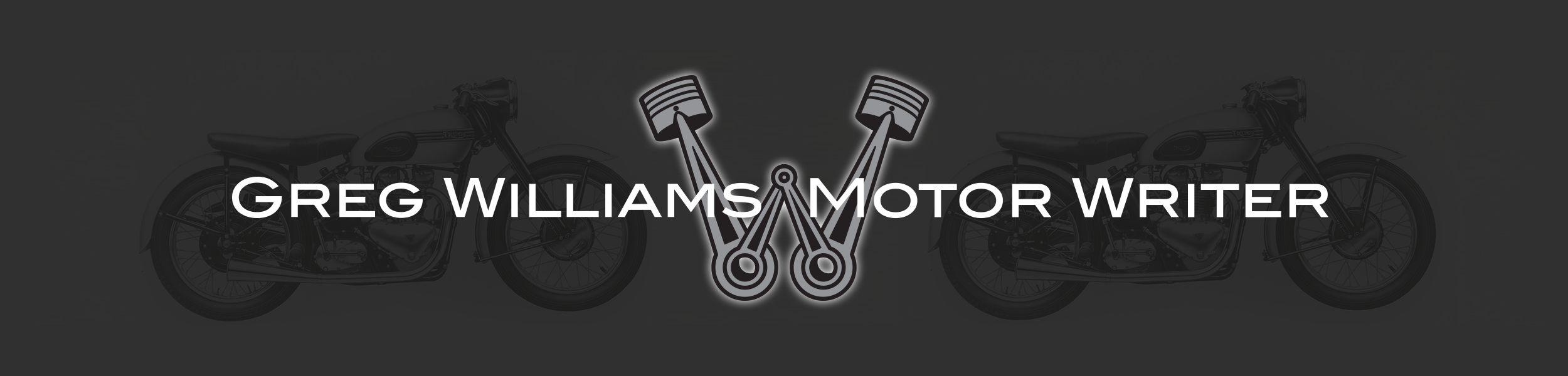

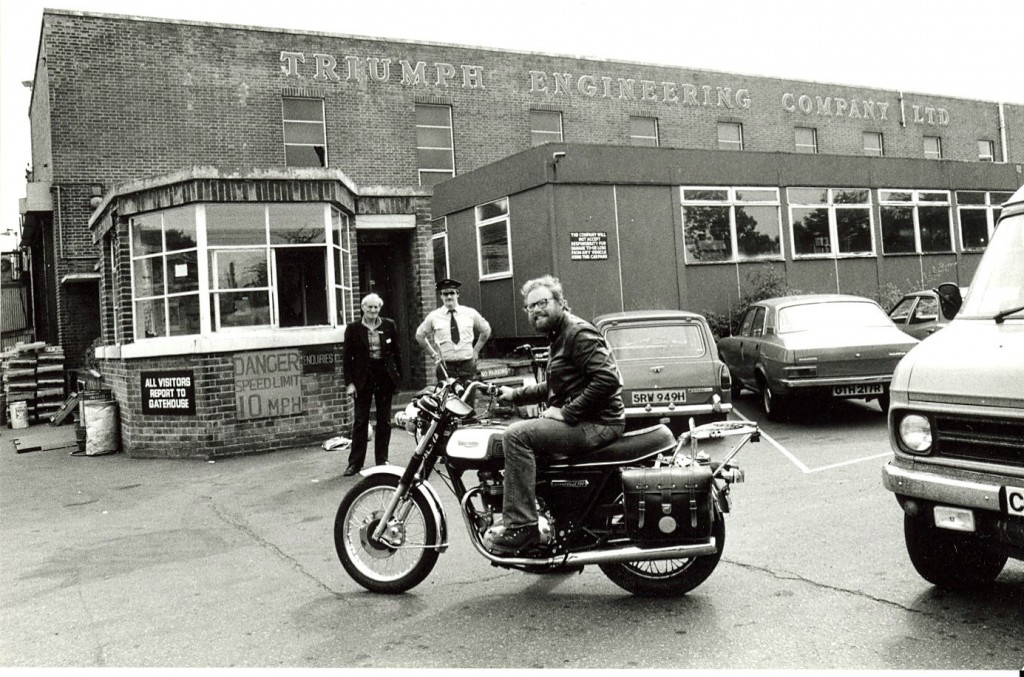

Scan of the 1936 Ariel brochure shows the OHC Square Four.

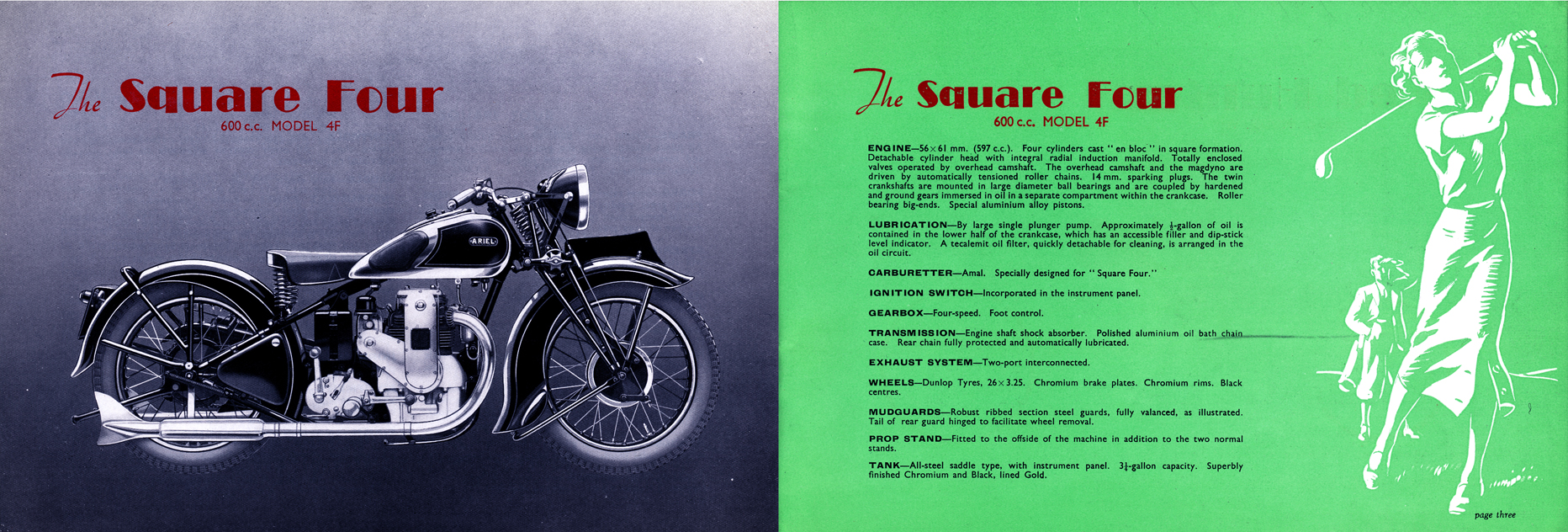

Next, in the 1936 Ariel full-range brochure in the collection, nothing has changed on the Square Four Model 4F. Ad copy states: “ENGINE – 56 x 61 mm (597 c.c.). Four cylinders cast “en bloc” in square formation. Detachable cylinder head with integral radial induction manifold. Totally enclosed valves operated by overhead camshaft. The overhead camshaft and the magdyno are driven by automatically tensioned roller chains. 14 mm. sparking plugs. The twin crankshafts are mounted in large diameter ball bearings and are coupled by hardened and ground gears immersed in oil in a separate compartment within the crankcase. Roller bearing big-ends. Special aluminium alloy pistons.”

In my 1937 brochure, Ariel claims to be one of the most highly advanced motorcycle engineering firms. “This enviable position has only been attained by years of painstaking efforts on the part of our Technicians and Craftsmen,” the copy states, “to produce not merely a good motor cycle but a machine which for outstanding design and excellence of material cannot be surpassed. Substantiation of this statement is to be found in the introduction, five years ago, of the first Square Four power unit, acclaimed by Automobile Engineers and practical Motor Cyclists throughout the world as the greatest advance in the evolution of the Motor Cycle.

Ariel copywriters continued: “During the intervening period, experience and research have enabled us to carry out considerable improvements to this unit, so that the 1937 editions of the 600 c.c. and 1000 c.c. Square Fours are undoubtedly the most outstanding Motor Cycles of all time.”

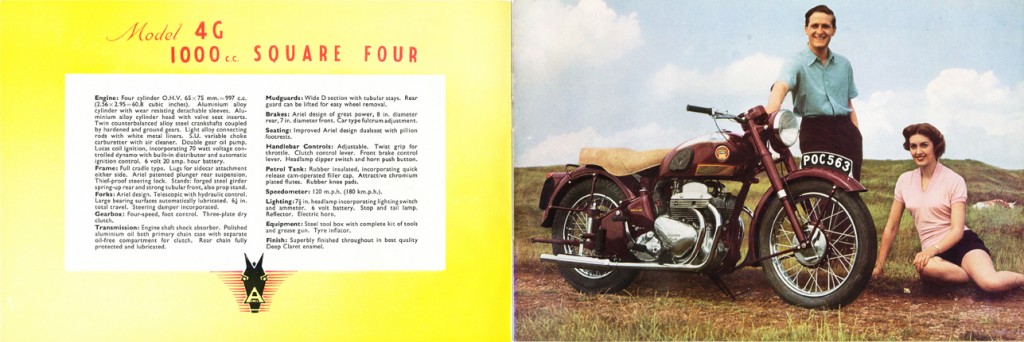

Quite a mantle Ariel has bestowed on their big multi, and it was indeed the top of their range. But Ariel’s big change for 1937 was the redesign of the powerplant, enlarged to 1,000cc on the Model 4G, and remaining at 600cc on the Model 4F. The units disposed of the overhead camshafts, and the valves were now operated by short pushrods acting on a centrally located cam in the center of the crankcase, while the forward-facing carburetor moved to the back of the engine.

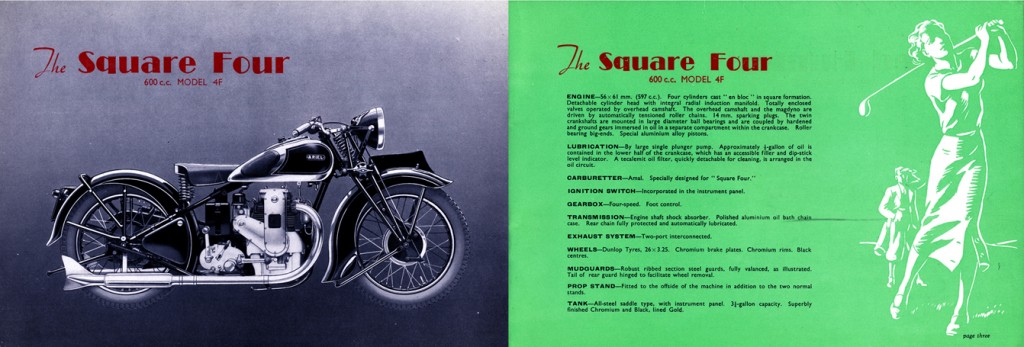

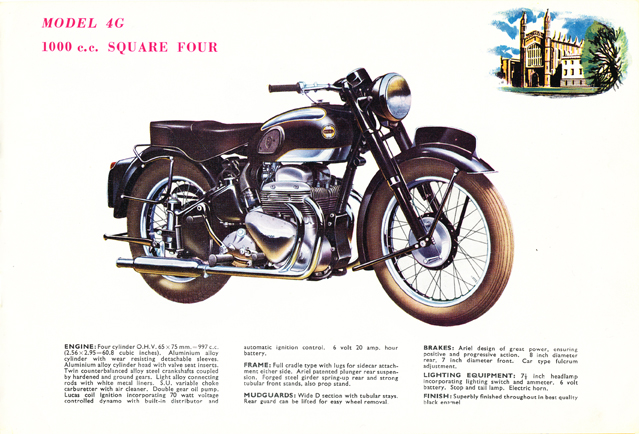

Scan from the 1938 Ariel full-line brochure shows the Model 4G 1000cc Square Four.

By 1938 Ariel has dropped the 600cc Model 4F, and only the 1,000cc Model 4G remains, which is unchanged with rigid frame and girder fork. Somewhat surprisingly, in 1939, Ariel lists the Square Four De Luxe 1000cc Model 4G together with a Square Four Standard 1000cc Model 4H and, once again, the smaller 600cc 4F. Differences between the De Luxe and Standard models seem limited to valanced fenders for the previous and regular open fenders for the latter. The De Luxe was also equipped with a prop, or side stand. New for 1939 was Ariel’s spring frame, essentially a plunger-style rear suspension that could be ordered, at extra cost, to fit any of the Square Four models.

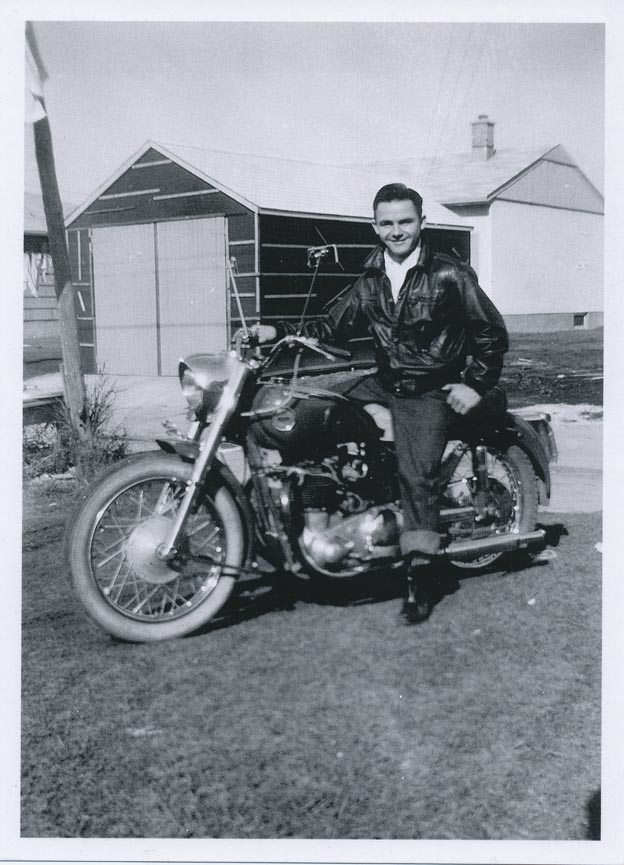

Ariel quit civilian production during the war years, focusing on building stout singles for military use. They were quick to return to motorcycle manufacturing, however mostly for overseas markets, in 1945. According to Bacon’s book, the Square Four appeared again but only in the 1,000cc size looking much as it had in 1939, with rigid frame and fully valanced fenders. Telescopic forks and standard rear suspension appeared on the Square Four in 1946.

Attempting to shed some weight Ariel updated the Four’s powerplant in 1949, replacing the cast iron cylinder block and head with all-alloy components in what became known as the Mark I Square Four. The Lucas magdyno unit was ditched in favor of coil ignition and 70-watt dynamo with a car-type distributor driven by skew gear. Timing cover inscription changed from ‘1000’ to read ‘Square Four’. In 1950 the speedometer was relocated from its traditional tank-top instrument panel to the top fork, and in 1951 the instrument panel was gone in its entirety. Speedo was now housed in an alloy casting that doubled us the upper fork crown.

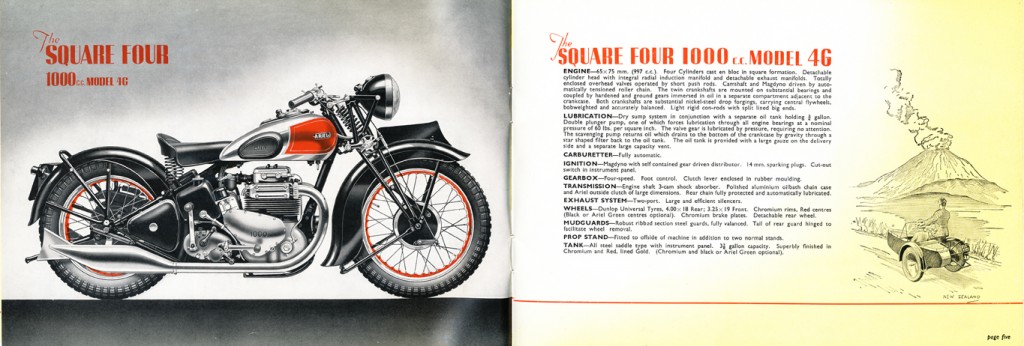

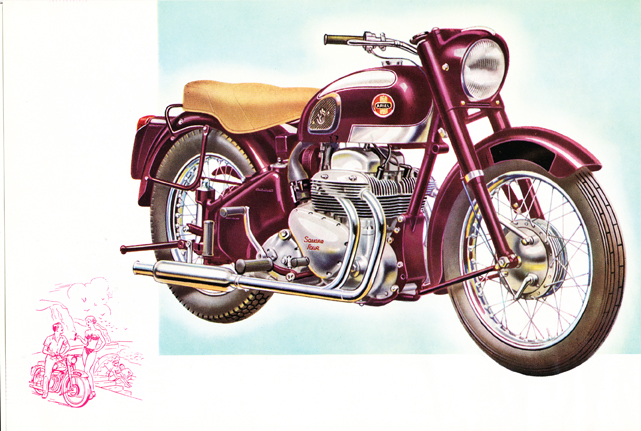

From 1952, an artist’s rendering of the Model 4G 1000cc Square Four with new fork and alloy block and cylinder head.

My next Ariel brochure is dated 1952 and the Four is shown with its new fork top and tidy looking close-pitch finned all alloy cylinder block and head. Changes occurred again in 1953, though, and this ushered in the Mark II Square Four and its engine, instantly recognizable by four separate exhaust headers.

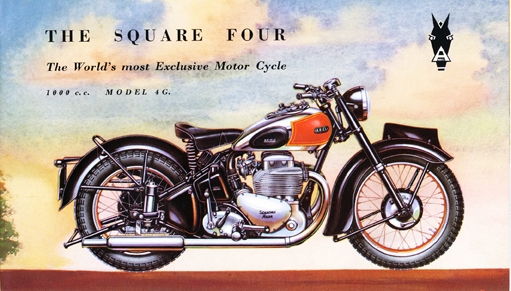

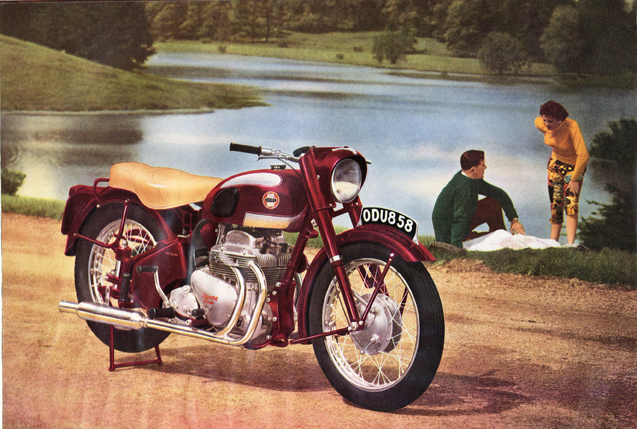

From 1954, the Mark II Square Four with easily recognizable four-pipe exhaust.

Both the Mark I and Mark II models sold side by side in 1953, but by the time of my 1954 brochure only the Mark II was left. Gone was the sprung solo saddle, replaced by a long bench-type seat. Remaining was Ariel’s plunger rear suspension, and the motorcycle with its taller seat took on an ungainly stature.

Now in 1955, the Model 4G Square Four — unsure the models would entice anyone to buy.

Little changed in 1955 but the addition of a fork lock. Ariel updated the 1956 Square Four with a hooded headlight and fork cover featuring a top panel with speedo, ammeter and light switch. At the lower end of the fork was a new full-width light alloy hub. Rear suspension was still provided by the plunger frame, and that remained until the end of the line in the 1959 model. By that time Ariel had built a prototype Square Four with swingarm rear suspension, but the firm was phasing out all four-stroke production, focusing instead on two-strokes.

Ariel’s Square Four in 1956 shows the new headlight shroud, but little else in the way of updates, and again below in 1957.

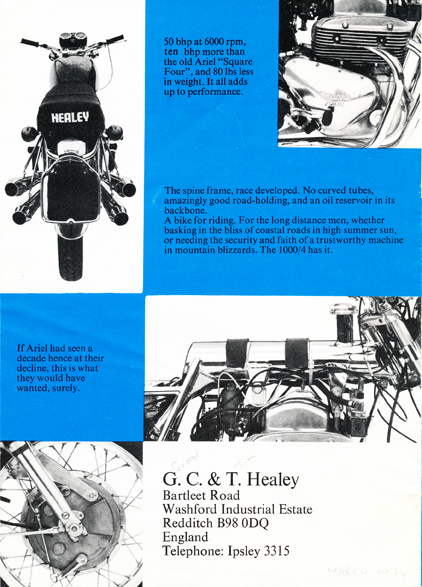

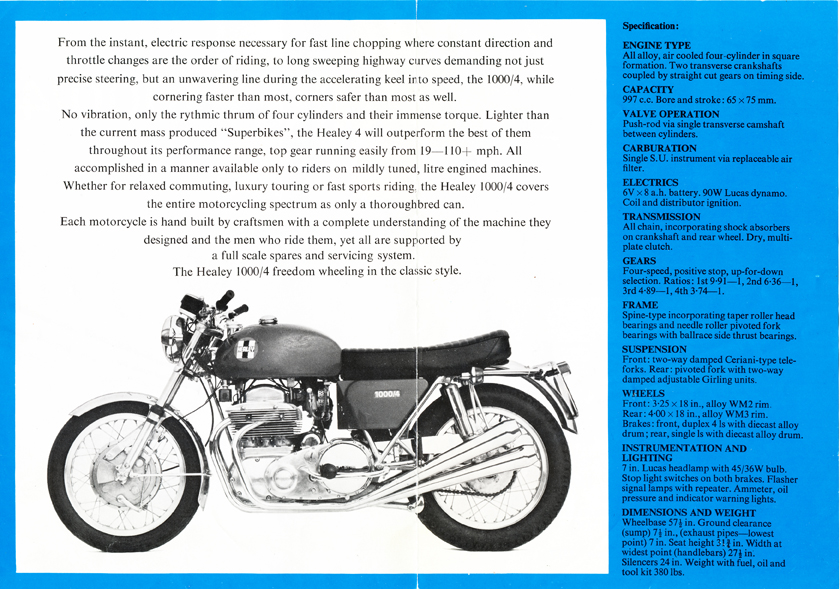

Redditch-based brothers George and Tim Healey became Square Four specialists in the mid 1960s, and by the early 1970s were building complete Healey 1000/4 motorcycles with the Square Four Mark II engine hanging from an Egli-style spine frame, in something of a café racer pose. “50 bhp at 6000 rpm,” claims the Healey brochure, “ten more than the old Ariel “Square Four”, and 80 lbs less in weight. It all adds up to performance.”

It continues: “The spine frame, race developed. No curved tubes, amazingly good road-holding, and an oil reservoir in its backbone. A bike for riding. For the long distance men, whether basking in the bliss of coastal roads in high summer sun, or needing the security and faith of a trustworthy machine in mountain blizzards. The 1000/4 has it.”

The first 1000/4 was built in 1971, and the Healey’s ceased production in 1976. By that time, as Bacon notes, “In its final form it (the Healey 1000/4) was not too far removed from Turner’s original concept – light, lively and exhilarating to ride.”

Not a Honda CB750-beater, the Healey 1000/4.