Mark Gardiner ‘Riding Man’ and One Man’s Island, by Greg Williams, Calgary

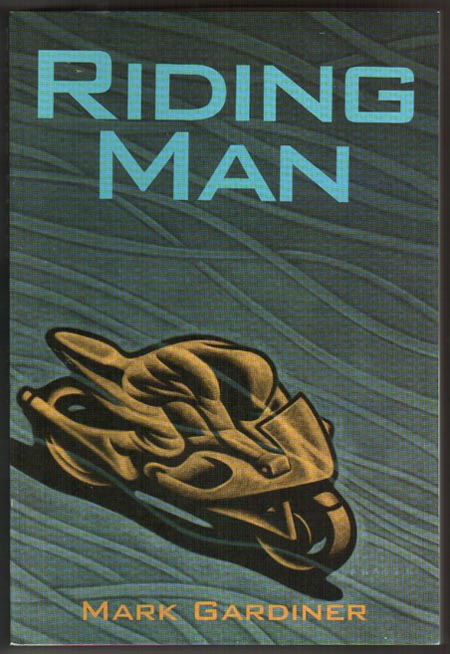

It’s finally here. Mark Gardiner’s book, Riding Man, is available. Riding Man details Gardiner’s personal odyssey as he dreams of — and ultimately races in — the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy. The book is available at Gardiner’s website, www.bikewriter.com, and the film, One Man’s Island, is available at www.onemansisland.com.

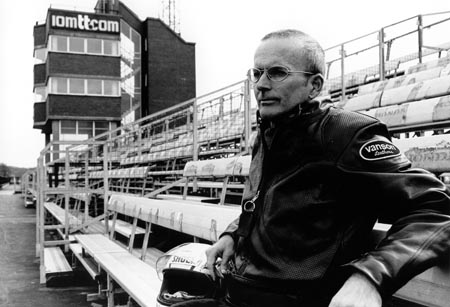

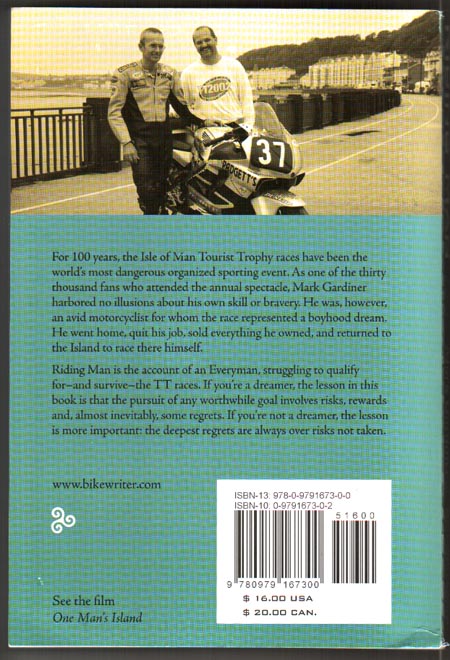

This is a piece I wrote for the Calgary Herald Driving section, and was originally published Sept. 26, 2003. Black and white photos courtesy Peter Riddihough.

The Isle of Man Tourist Trophy is the most historic and the most dangerous motorcycle race in the world. One Man’s Island is a documentary feature film about one man’s dream–to race in this prestigious event.

But One Man’s Island is not just about one man’s dream to ride a motorcycle in a race. As the film succinctly points out, everyone has a

‘TT race’ of their own.

Canadian and ex-Calgarian Mark Gardiner sold everything he had in late 2001. He moved in January of 2002 to the Isle of Man and began training for the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy Races–held annually in June.

But he wasn’t alone. In the late 1990s Gardiner was the creative director of an advertising agency. He met Peter Riddihough, who was just starting out producing television commercials in Toronto. During a lull in filming a TV commercial together, Riddihough listened as Gardiner told him about the TT race.

“I told him about motorcycle racing, and talked about wanting to ride in the Isle of Man TT,” Gardiner recalls during a phone interview from his home in Paris, France. “I told him what I planned to do–I was thinking of selling everything and moving over to the Isle of Man and pursuing this goal.”

On the very day Gardiner decided he would quit his job, sell, give away or abandon his belongings and move to the Isle of Man, Riddihough sent him an email.

“He wanted a real story to tell,” Gardiner says.

In 1907 the first Tourist Trophy was held on the Isle of Man, a tiny island in the middle of the Irish Sea. Racing on mainland Britain was not allowed, as public roads could not be closed and there was a blanket speed limit. The Isle of Man perhaps saw a tourist opportunity, and invited motorcycle manufacturers and racers to run an event on their public roads, closed specifically for such races.

Referred to as the ‘mountain course’, the track consists of 38 miles of twisting and undulating road that runs through villages and countryside and then into the mountains of Man. Rather than truly racing against an opponent, the TT is run against the clock–riders are sent out 10 seconds apart.

Gardiner was born in Vancouver, lived in Switzerland, and arrived in Calgary at the age of 16 for his high school years. He bought a small Kawasaki KZ100 motorcycle while attending Queen Elizabeth High School. In an effort to emulate the exploits of American dirt track oval racers–photos of which he had seen in copies of Cycle Magazine–Gardiner set out to practice on a track near the current Blackfoot Motorsport Park.

“It was a disaster, I crashed that Kawasaki until my body was one giant bruise,” Gardiner recalls. “I didn’t have what it takes.”

He stopped riding, but several years later Gardiner realized he had never actually learned how to race his motorcycle.

“It started to come back to me when I was well into my 30s that I had always wanted to be a motorcycle racer,” he says.

With his career in advertising firmly established, Gardiner had a little time and a little money to invest in becoming a motorcycle racer. He attended beginner and intermediate race schools at Shannonville, Ontario and found out he was quite comfortable at speed on a road race course.

Going even further, he bought a 1988 Yamaha RZ350 which he campaigned at Calgary’s Race City Motorsport Park. By the time Gardiner was 40 years old, he and the bike were developed enough that they won the Veteran’s class, and finished third in the Lightweight Sportsman class.

“I was having a terrific time, but I kept thinking if I could just win a real race I’d stop,” Gardiner says. It was about this time that he started work for an ad agency in the Maritimes, where he joined the Loudon Road Racing Society.

He began regularly racing at Loudon events on an MZ Skorpion, a single cylinder motorcycle. Although he was listed as an amateur, it wasn’t long before he was bumped up to a junior ranking. This meant he raced with a pro competition licence. It also meant he could compete in Expert events in American AMA National races.

“Riding the Skorpion in the AMA Pro-Thunder races was a hopeless challenge, it was an utter dogfight and I was constantly riding to the absolute limit not to finish last,” Gardiner says.

But in the back of his mind, Gardiner knew he now had the licences required to compete at the Isle of Man TT–all he needed was FIM recognition–which he received.

Gardiner initially wanted to campaign his Skorpion single, but in 2002 the TT scrapped their single cylinder class and instead instituted a 600 c.c. production class. It was now or never for Gardiner–and Riddihough was ready to film the entire process including Gardiner’s preparations to race in the TT.

“I sold everything, and arrived on the Isle of Man with what I could carry–some clothing and a bicycle.

“My life on the Isle of Man was that of a monk,” Gardiner adds. “My meditation was the island, and I pedaled my bicycle around the course every day–I spent every day looking at it, smelling it and feeling it.”

Using his credit card, Gardiner leased a 2002 Honda CBR600FI from Padgett’s, an Isle of Man motorcycle retailer. He began slowly breaking the machine in by riding the entire TT course. He was racing the course in slow motion, and would imagine himself weighting the footpegs, or applying pressure with a knee on the fuel tank.

Riddihough was there for every step.

“When Mark first started talking to me about what he wanted to do, I told him I’d quit what I was doing and go with him,” Riddihough says. “I’m not a motorcyclist, I can’t even ride. But this story fundamentally had an appeal as a human interest story–giving up everything to pursue a dream. Beyond the context of the motorcycle race, the story is universal.”

The 36 year old Riddihough wasn’t interested in just the race, his desire was to capture the entire process–in essence he felt it would be more meaningful if the film took the audience on the entire journey. He filmed by himself using digital cameras, and built and installed a camera on Gardiner’s motorcycle for some dramatic on-board footage.

For the race Gardiner had help from a number of Calgarians willing to make the trek to the Isle of Man. Paul Smith is the service manager at GW Cycle, and he arrived to tune and take care of the Honda motorcycle. Alberta College of Art and Design instructor and motorcycle enthusiast Bill Rodgers helped work the pit stops, as did SAIT mechanical engineer and Mark’s nephew Kris Gardiner.

After it was all over, Riddihough came back to Toronto and edited over 140 hours of film. To his credit, One Man’s Island was an official selection at the World Film Festival in Montreal, and is an official selection at the Calgary International Film Festival 2003.

The film comes close to being a Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance for motorcycle racers, but the story is about so much more than just the TT race. It is a story of the universal human condition and the importance of never giving up on a dream. As for the 2002 TT and Gardiner’s results, take in the film. One Man’s Island screens at the Uptown 2 on Tuesday, Sept. 30 at 6:45 p.m.

–That was the last line in 2003. As stated at the beginning, buy your own copy of One Man’s Island, and Gardiner’s book, Riding Man.

Excerpt from Riding Man, by Mark Gardiner

Copyright 2006, Mark Gardiner

Once again, we stage on dry pavement, but by the time I launch, it’s streaming rain. My practice partner passes me on the brakes at Quarterbridge. This is getting old. I concentrate on hitting the apex, and get a reasonable drive off the corner, the rear spins up in the wet, but the Honda holds it’s line, and I have a good run to Braddan church.

At the church, I notice something: the wake of the bike ahead of me is still visible in the standing water on the road. He can’t be far ahead. Maybe I have an epiphany, aiming for a late apex, winding the throttle on, and letting the spinning rear tire slide around until I’m pointing down the road. Over the next few miles, riding the CBR as though it was a little dirt bike, I catch and pass several guys. No one passes me.

I close on my next victim at the top of Barregarrow. He’s in black leathers, and another Newcomer–I see by the orange vest. Even in this weather, the run down to the bottom of Barregarrow is top gear. There’s a hump where the road crosses a stream, and it kinks left around a building. It’s the hump, not the corner, that limits your speed. The apex marker is a cast-iron drainpipe. The first time I came through here, I found it damned intimidating–and that was on a bicycle.

I know that I’m going to carry a lot more speed through here than this guy. I plan to pass him on the bumpy straight just beyond. But as I adjust my speed and commit, Mr. Orange Vest panics and brakes extra hard. Leaned over, in the rain, with the bike unsettled by the bridge, there’s no way I’m stroking the brake. I literally squeeze through the gap, brushing the drainpipe with my left shoulder, ‘brushing’ him a little harder with the CBR’s muffler. When I look back, I’m relieved to see that he’s still on his wheels.

This Post Has 0 Comments