A story written about the now legendary Death Valley vintage motorcycle run. I attended in Oct., 2001, and this article ran in Walneck’s Classic Cycle Trader.

MAX BUBECK’S DEATH VALLEY XV RUN

Max Bubeck — legendary Indian motorcycle rider — has hosted his California Death Valley Run for 15 years. He started this now infamous antique and vintage motorcycle tour in 1986 and except for 1987, Bubeck and his unique run have visited the Valley every year.

And at the invitation of Gary Breylinger, now of Montana and one of the riders at Death Valley II in 1988, I welcomed the opportunity to be a part of the Death Valley Run XV held in early October, 2001.

There were 78 registered participants at D.V. XV, with out-of-state plates from Colorado, Florida, Iowa, Nevada, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Texas and Washington.

The D.V. Run now boasts international recognition and motorcyclists from Canada, England and Germany enjoyed Bubeck’s hospitality, the desert, and ideal riding conditions.

At 84, Bubeck’s reputation precedes him. His adventures and misadventures could fill a tome, and he is currently compiling his most memorable experiences in book format. Highlights of Bubeck’s illustrious past will give a sense of his deserved nickname–‘Fearless Leader’.

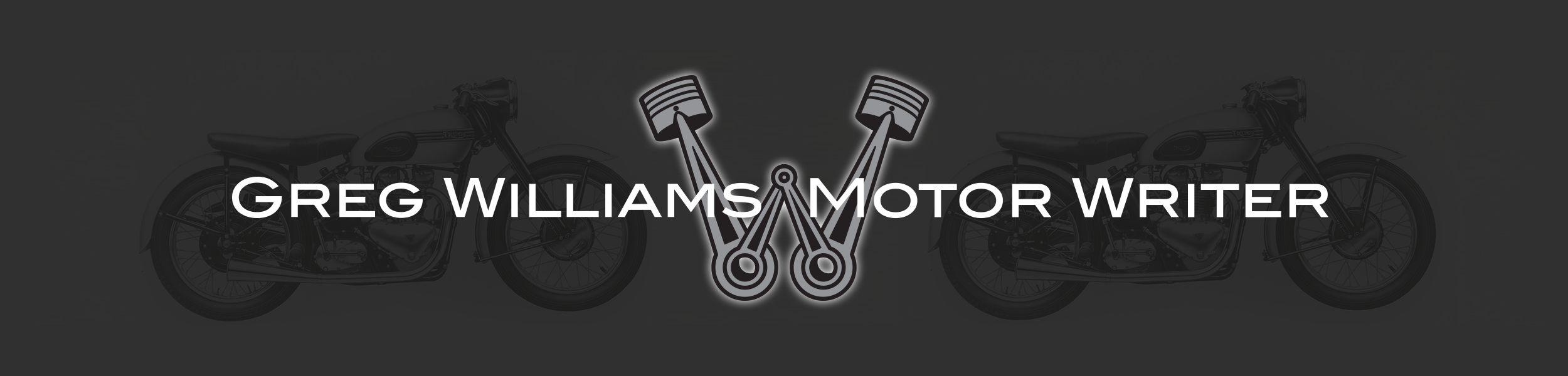

Bubeck’s first motorcycle in 1933 was an Indian 101 Scout, which he then swapped for a 1930 Indian Four. In 1936, he purchased a new ‘upside down’ Indian Four. In 1939 he bought a new Indian Four from Floyd Clymer which he modified to suit his tastes. Bubeck still rides this motorcycle.

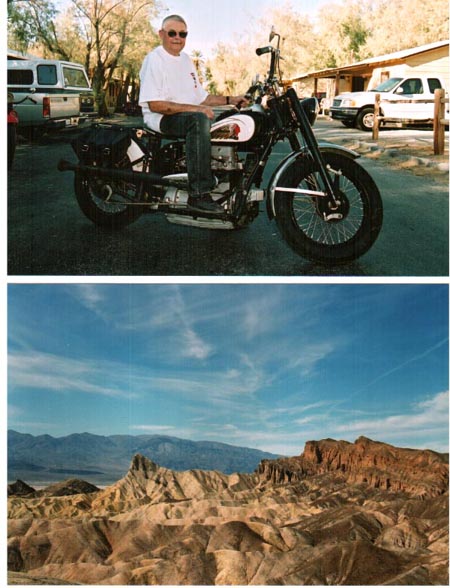

Max Bubeck and his 1939 Indian Four, and the

view from Dante’s Peak at the south end of

Death Valley

Between 1937 and 1979 Bubeck rode in 32 Greenhorn Enduros, and declared, “I finished 24 of them.” He rode his 1939 Indian Four in the 1947 Greenhorn, and was the overall winner. In 1962, he again won the Greenhorn, this time riding a 1949 Indian Warrior vertical twin.

In 1955, he laid out a cross-country enduro route that included the south end of Death Valley–he called it the Jackass Enduro. Of the name, Bubeck explained, “I came across a bleached burro skull, and I strapped it onto my Indian vertical twin. That skull became the trophy for the Jackass Enduro.”

In the late ’60s and early ’70s, Bubeck rode Hodaka trail machines in Southern California and District 37 enduro events. He was No. 1 in points from 1969 to 1972, and as he proudly pointed out, “I was 52 through to 55 years old, and I was no kid then.”

He continued, “I still have the urge to surge, and when I get so that I can’t go fast anymore–well, then I’ll slow down.”

In the summer of 2001 Bubeck rode his 1939 Indian Four from Palm Springs, CA to Springfield, MA, for Indian’s 100th birthday bash. Accompanied by two friends, Bubeck covered 450 miles a day, at 60 to 65 mph. And Bubeck was the only one to ride the total 3,554 miles aboard his motorcycle. Both Butch Baer and Tim Bresnahan completed the trip in an air-conditioned pickup, with their motorcycles relegated to a trailer.

And it was on this 1939 Indian Four–a machine which has accumulated more than 180,000 miles–that Bubeck toured his guests for Death Valley XV.

Death Valley National Park is an extraordinary desert and mountain environment, covering 3.3 million acres of eastern California. Badwater, in the south part of the Valley, is the lowest point in the U.S. at 282 feet below sea level.

The first stop on day one of Bubeck’s tour was the now defunct Harmony Borax Works, just north of what was home-base for the run–the Furnace Creek Ranch. This modernized facility started life as the Greenland Ranch. Originally, the ranch had date palm groves, and supplied hay for mules working at the Harmony Borax Works.

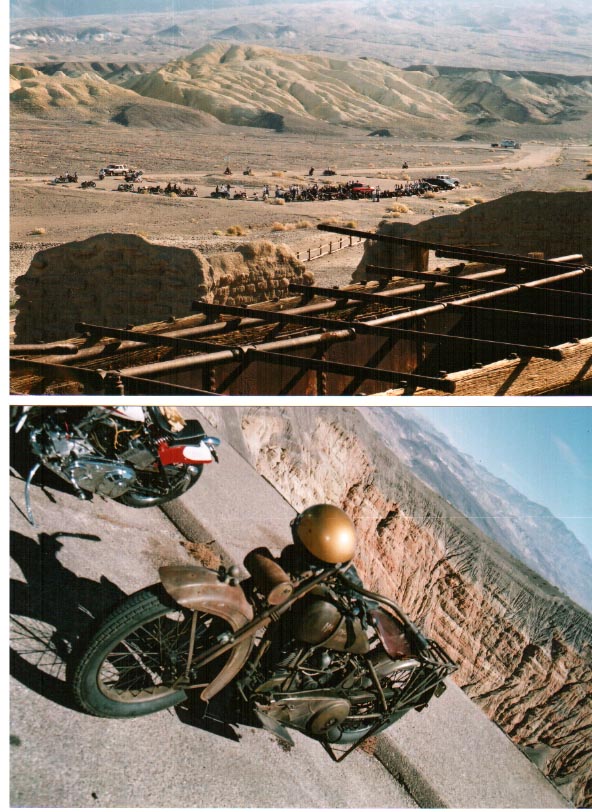

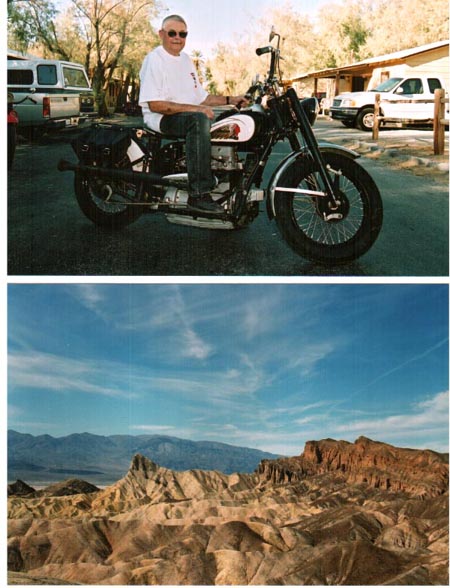

A view of Death Valley from the Harmony

Borax Works, and Ubehebe Crater with

Leonard Miller’s 1926 Harley-Davidson JD.

A quick tour of the decaying remains of the Works, and it was back on the motorcycles to ride 75 miles north to Scotty’s Castle.

Death Valley is a rider’s paradise for several reasons. The first advantage I noted as I rode Breylinger’s 1967 Harley Davidson Sportster was the absence of large trucks–they aren’t allowed within the park. Second, it is so warm in early October that a T-shirt and jeans, together with a helmet–California is a helmet-law state–were adequate apparel for this D.V. rookie. Temperatures can reach 105 degrees in October, but during D.V. XV, participants were blessed with 90 to 95 degree days.

From the Harmony Works, the road north to Scotty’s Castle gently rises from the valley floor to an elevation of 3,000 feet. A guided tour of the Castle is a must, and as our hostess explained, Scotty’s Castle wasn’t really prospector Walter Scott’s home, but a desert retreat for Chicago insurance executive Albert Johnson and his wife Bessie.

Scott and Johnson had formed a partnership in 1904 and together the pair searched for gold in Death Valley. Although Johnson never found gold, he did find the desert climate agreeable. He and Scott would camp in Grapevine Canyon at the north end of Death Valley and he began to realize that this Canyon was an ideal site for a retreat.

Construction began on the Spanish-style villa in 1922, but it didn’t take shape until 1925. And while the Johnson’s called their villa Death Valley Ranch, newspapers and visitors came to call it Scotty’s Castle. Even though the estate was built with Johnson’s money, he allowed Scott the limelight, and defended Scott’s claims that the villa was his ‘shack.’

The Scotty’s Castle stop offered fuel and food, and the next rendezvous was six miles west at Ubehebe Crater, a 1/2 mile wide, 770 foot deep pock mark created more than 2,000 years ago by volcanic activity.

While at the Crater, I caught up with Leonard Miller of Sacramento, CA. Miller rides an original and unrestored 1926 Harley-Davidson JD, which is rich with patina.

“I bought it looking exactly the way it looks today,” Miller said. “I was at a swap meet, and this machine, with a sidecar, came in on the back of a trailer. I offered $5,500 for the rig 14 years ago, and apart from removing the sidecar I have not touched it, and I have never washed it.”

Miller’s JD made the trek back from Ubehebe Crater to Furnace Creek Ranch without incident. Roy Burke of Oregon also made it back, but encountered two small problems–his motorcycle was wet sumping, and a tire developed a slow leak.

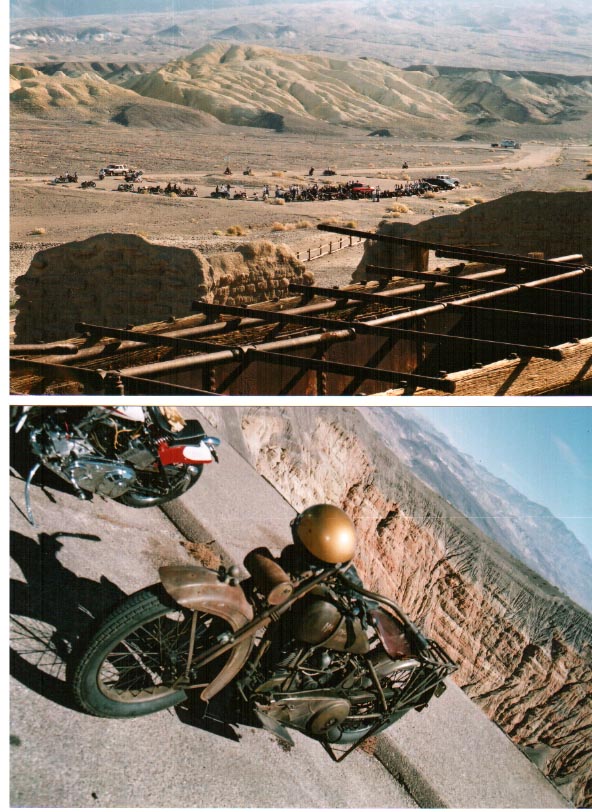

I had caught sight of Burke and his impressive single-cylinder 1914 ‘Roy Burke Special’ Indian prior to leaving in the morning. Burke’s special is based on a 1914 single-cylinder Indian engine, but just about everything else is hand-made, including his own overhead valve conversion. Moving the valves over the piston dramatically increases the horsepower from a meager 3 1/2 or 4 to an astonishing 15 or 20.

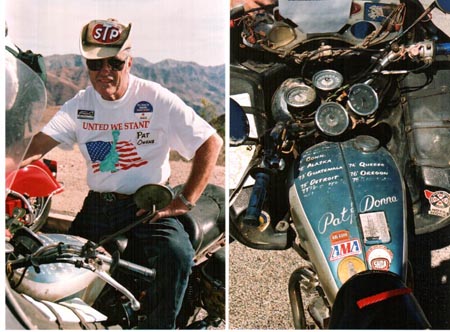

Roy Burke and his 1914 Roy Burke Special

“These old single-cylinder Indians used to go 30 or 40 mph–now this one goes 75 or 80,” Burke remarked early in the morning. He created his own frame, and appropriated a set of Japanese forks to suspend the front.

“We’ve been playing with these singles for about 20 years, and we’ve broken everything that can be broken–rods, crankcases, crankpins–but this engine has all Indian Chief parts inside it now.”

Sadly, Burke’s Indian was retired to the trailer, and wasn’t running for day two of Death Valley.

Bubeck rallied the riders on day two and led his guests to Devil’s Golf Course, Badwater and Artist’s Drive. My ride had been Breylinger’s ride the first day, a 1947 Royal Enfield J2.

Light and shadow create a variety of hues on the mountains and the flats that make up Death Valley. No where is this more apparent than on Artist’s Drive, a short paved circuit off the main road that loops through wind and water worn rock. While riding along the one-way road, the landscape changes from shades of purple to brilliant white.

A brief lunch stop back at Furnace Creek Ranch, and the vintage iron was again prodded to life for the last leg of Bubeck’s Death Valley tour. Zabriskie Point, 20 Mule Team Canyon, and then the final stop–Dante’s View.

I had been told that the road to Dante’s View was unlike any other. Much like the highway north to Scotty’s Castle, the pavement to Dante’s View slowly rises from the south end of Death Valley. And the road has everything, twists, straights, hairpins, and finally a 14 per cent grade for the last 1/4 mile.

Riders who reached the top first parked their machines, and watched the other motorcyclists make their way up the grade, through the hairpin, and grind up the final stretch in low gear.

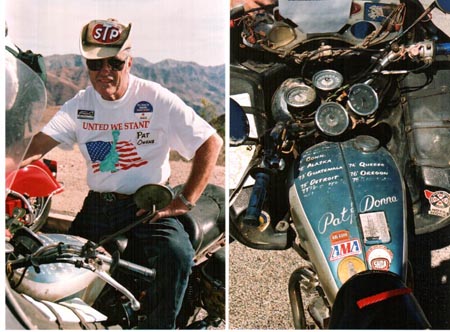

At the top, I met Pat Owens of Temple City, California. Owens was riding a 1970 Triumph T120RT Bonneville.

Pat Owens with his 1970 Triumph T120RT Bonneville

Owens and his wife Donna have more than 450,000 documented miles aboard the blue and silver Triumph, having ridden it twice to Alaska, and as far as Guatemala and Quebec.

“I’ve had this bike since 1970, and I am the one and only owner,” Owens said. “This bike has its original crankcase and crankshaft, and all of the gears except one in the transmission are original. I use half STP oil and half 140 weight gear oil, and I call the bike the ‘STP special’.”

The hill down from Dante’s View affords an opportunity to mount a coasting race. Halfway down the hill, motorcycle engines are cut, transmissions are placed in neutral, and they’re off–rolling down the grade to see who will glide the farthest. Dee Cameron of California picked up the long-distance coasting award aboard his Velocette.

At the banquet that evening, Bubeck presented an award to everyone who rode, each one specific to the recipient in some way. And the next three days were spent driving the return 1,500 miles to home–plenty of time to mull over the sights and sounds of Death Valley Run XV.

click on the thumbnail for larger image

click on the thumbnail for larger image