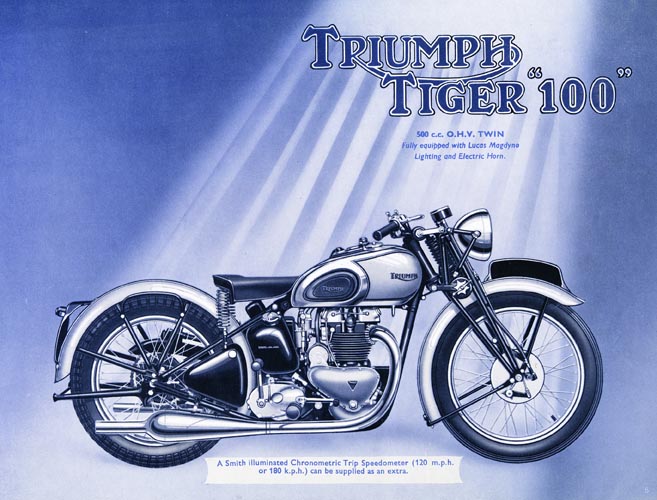

1939 Triumph T100 ‘custom’

When I acquired an original paint 1939 Triumph Tiger T100 frame and gearbox the fun began, as I wanted to put together a race-style bike like someone would have built or modified either pre-war or immediately post-war.

Making it a rolling chassis was my first priority, and a Norton pre-war girder fork was fitted to the frame, followed by a Norton 16H hub and brake. The rear wheel hub is late model Triumph, the kind with the sealed bearings rather than taper style rollers. The larger diameter axle had to have flats machined in it so it would slip into the dropouts. The modern brake plate was trimmed of its dust ring, and the brake shoe pivot was sweated out and a new one machined up and TIG-welded to the plate by Derek Pauletto at Trillion Industries. This new piece slides into the channel on the frame and acts as a brake plate retaining device. The rims — 21″ front and 19″ rear — came from Central Wheel Components in the U.K., and Buchanan’s in the U.S. laced everything together with stainless steel spokes. Front tire is ribbed 3.00-21″ Avon, and rear is 3.50-19″ Avon Speedmaster.

A mangled Triumph 3T rear fender was fixed using the removable rear portion. A section of the main fender had to be cut out, with a section of the rear welded in place by Derek Pauletto. I never intended to run a front fender, but more on this later.

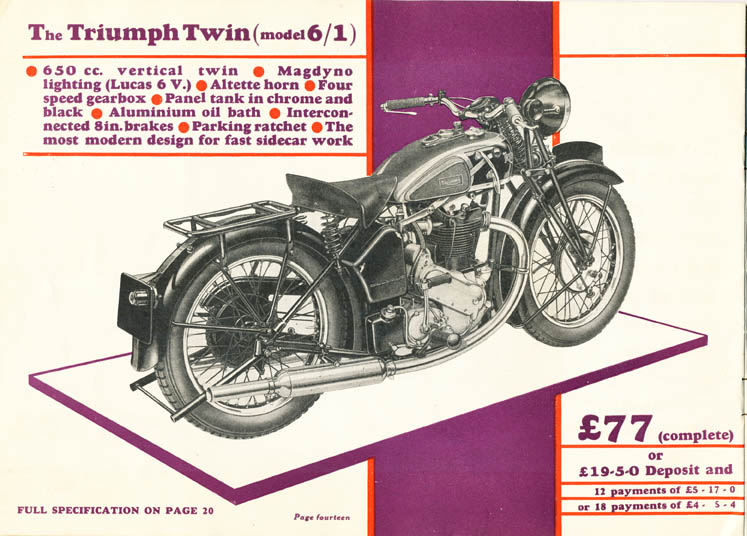

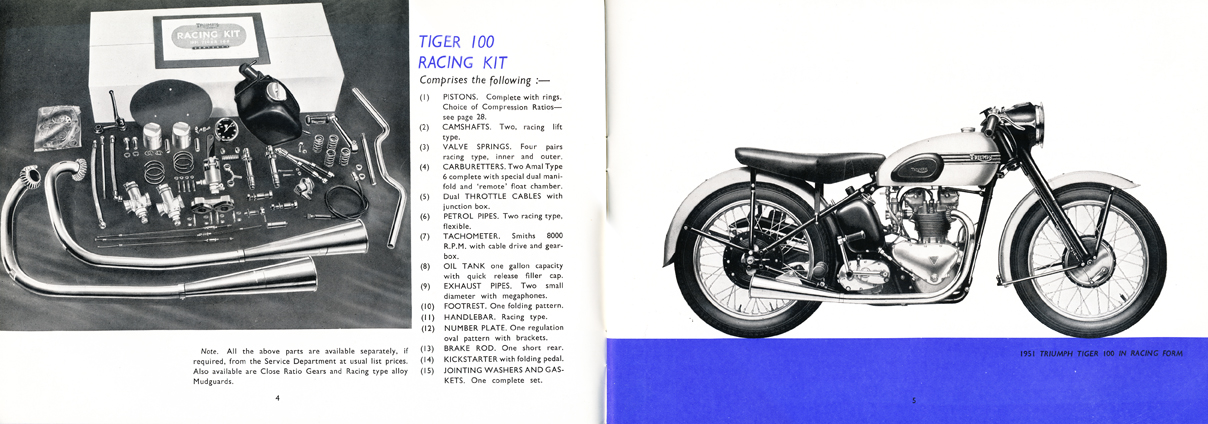

Meanwhile, the hunt was on for a set of pre-war engine cases. I missed a set that was for sale locally at a swap meet. The purchaser immediately put them up on eBay and quadrupled his money. Thanks to Les Binnell of Ontario, he sold me a set of his surplus cases for a reasonable price, and a 650cc Triumph crank was found. SRM provided proper shell bearing connection rods. The barrels came out of England, as did the head. Motoparts in Edmonton machined the crank and fit the rods and new +.060 pistons to the bored cylinders. A timeworn set of primary cases turned up on eBay, and by now, it became evident that the parts I was gathering all had a certain amount of ‘age’ to them.

I liked this worn look, so instead of going for a restoration, the pieces were cleaned, and cracks or broken threads repaired, and then put to use. The ‘stroker’ engine was carefully assembled by Neil Gordon, and placed in the frame by Neil and Bob Klassen. As a paraplegic, I don’t ride but still enjoy getting my hands dirty playing with these things and I rely on a network of friends for many of the heavier jobs. I rebuilt the gearbox, which was really in nice shape, and used an early four-plate Triumph clutch.

Plans were to run a Lucas headlight with ammeter and switch panel and a plain gas tank. But when John Whitby turned up with the swap meet find 5T tank that has thick red paint — likely applied decades ago by some biker with good intentions — it was too good not to use. I had some pieces of a dash panel, and those went to use on this project.

Because I was now running a tank top instrument panel, however, I couldn’t run the headlamp with the gauge and switch. A source in the U.S. told me he had a nice old Lucas with original chrome, and that he’d be happy to send it to me. I couldn’t believe it when it arrived, because it’s the correct 8″ lamp for a Triumph T100, and has the original fluted flat glass and reflector — and after it got here, he said he didn’t want anything for it, that he was happy it had a home. I packaged up one of our Modern Motorcycle Mechanics, Second Edition Reprints and a copy of Prairie Dust, Motorcycles and a Typewriter and mailed it off as a thank you. However, with that big headlight up front it looked unbalanced, and that’s why a Wassell ribbed fender, salvaged years ago from a Velocette restoration project, was cleaned up and put into service. Rear taillight is a reproduction Crocker, and it’s a great piece with a real glass lens.

A reproduction Lycett saddle frame was sectioned 5″ to narrow up the back end and new seat spring mounts made to suit. Up front, a 1″ diameter handlebar of universal pattern was flipped over for the crouched look, and I drilled holes for cables and mounted bar end levers. AMAL provided a new 1″ throttle as well the reproduction carburetor that has the float bowl mounted on the right, with idle and air screws on the left.

I had bits and pieces of a Lucas twin magdyno, but was missing an armature for the magneto. Gregg Kricorissian of Ontario modified a later armature, and completely rebuilt the instrument. A friend donated a well-used set of header pipes, and the megaphones were sitting on my shelf, These are actually the megaphones that came off of J.B. Nicholson (of Nicholson Bros. Motorcycles) personal 1939 Speed Twin. They were used when he was hillclimbing, and have plenty of scars to prove it. Just right, in other words. I made lightweight internal baffles using aluminum for the end caps, and Derek Pauletto TIG welded those together.

Neil Gordon and Bob Klassen were the first to fire the bike, and after switching the plug leads around on the head it lit right up. There were some oil leaks to remedy, but it now has just over 94 miles on the Smiths speedometer, rebuilt by Andy Henderson of Vintage British Cables. The bike’s ‘debut’ was at Ill-Fated Kustoms‘ 2016 Kickstart show at the Springbank Airport. There are many others who have fingerprints all over this motorcycle, including Dennis Firth, Mike Jones and Adam Franke. Thanks to all.