The Strange Death of the British Motorcycle Industry: in review

As the title suggests, Steve Koerner’s book shines more light on the plight of the English makers.

When Argentina shut its doors to British motor imports, the bell tolled louder for the English motorcycle industry.

In 1948 the South American country imposed strict import quotas and significantly higher tariffs. Losing this single important market helped cause Vincent, the English manufacturer of sporting v-twins, to misfire, and ultimately end in 1955 with the final motorcycle to roll from the Stevenage factory.

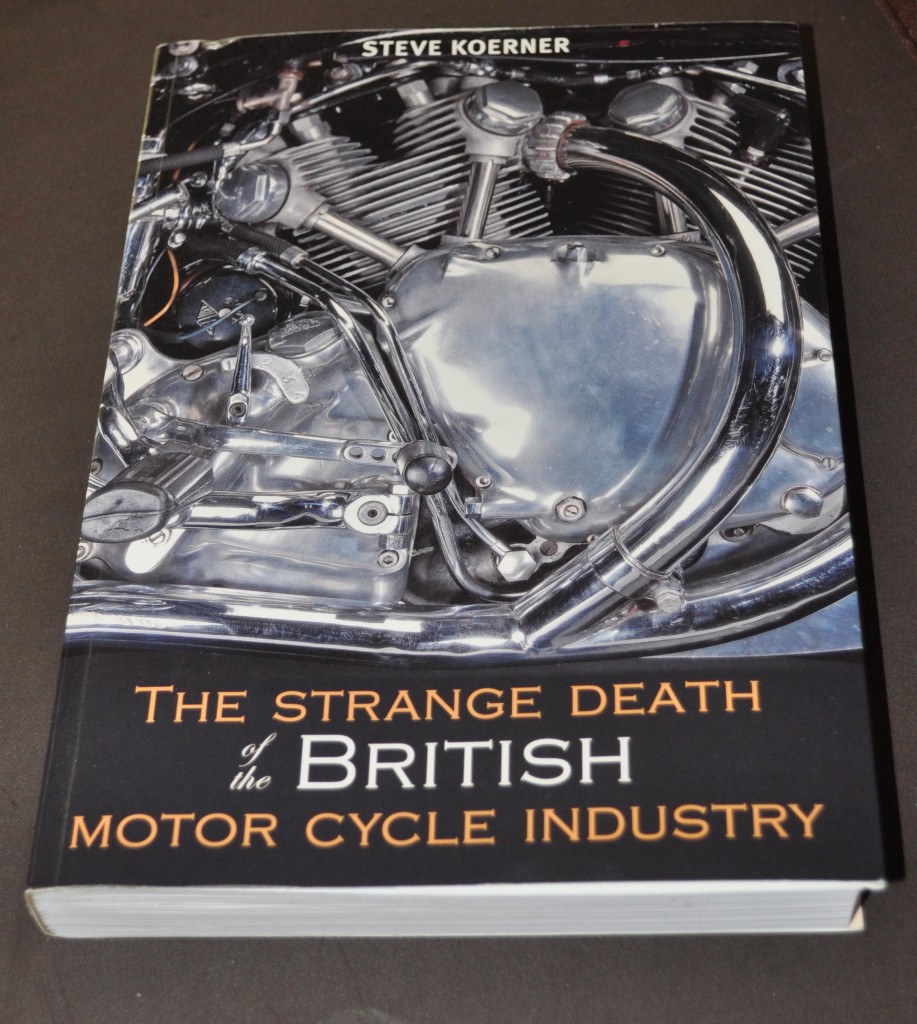

Such facts are discovered in a new book written by Vancouver Island historian Steve Koerner. The Strange Death of the British Motor Cycle Industry, published by Crucible Books, documents the downfall of the Brit-bike industry.

Why another book about English cycle makers? Several already investigate the topic, including Bert Hopwood’s Whatever Happened to the British Motorcycle Industry? and Hughie Hancox’s Tales of Triumph Motorcycles and the Meriden Factory. Most recently, Abe Aamidor tried tackling the subject in Shooting Star: The Rise & Fall of the British Motorcycle Industry.

Koerner attended University of Warwick in England, graduating with a PhD in Social History. Enthusiastic about things British, Koerner’s thesis investigated the history of the nation’s motorcycle industry. Rewritten for a broader audience, his thesis became the book, which is comprehensible and not an academic treatise.

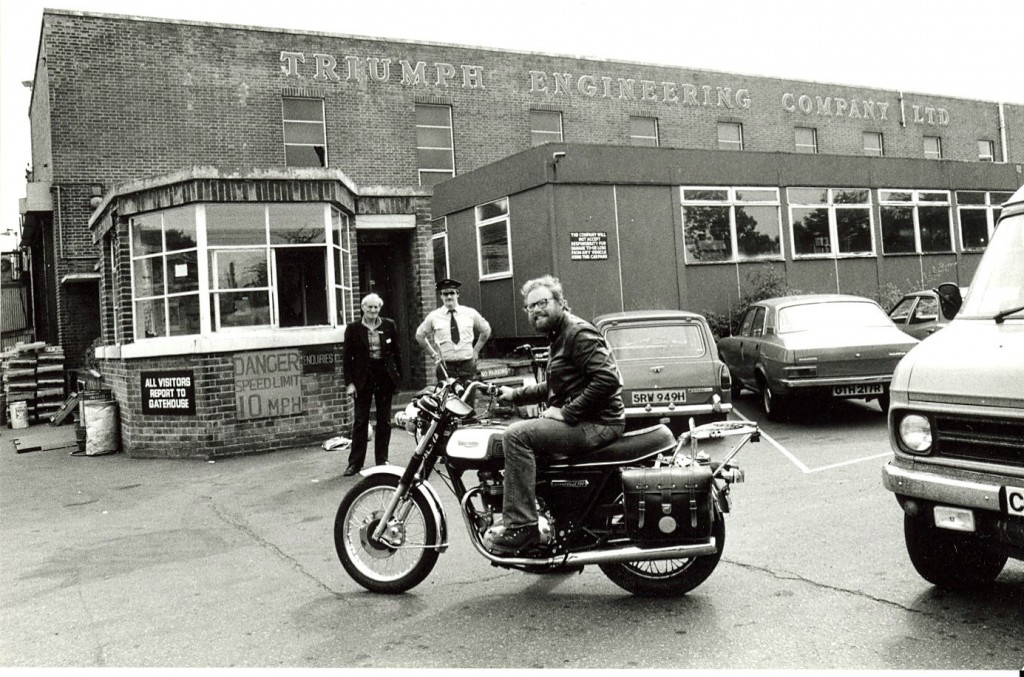

Photo copyright Steve Koerner. This photo was taken in June 1979 when Koerner was invited to tour the Meriden factory by its Workers’ Coop owners.

What Koerner accessed that nobody else seems to have are the annals of the Motor Cycle Industry Association in the Modern Records Centre at the University of Warwick library. “This is an amazing archive of information,” Koerner says of his original research, conducted in the 1990s. “It took me two years to get through it all. It contains materials about the industry and trade federation representing most of the manufacturing companies.”

Based in Coventry, the association was founded in the late 1800s, and archived information includes minutes, attendance books, guard-books, copies of telegrams, membership lists, periodicals, press cuttings, show catalogues and photographs.

Koerner mined more than just the association archive, also consulting surviving company papers of B.S.A. and Triumph, trade journals including the Cycle and Motor Cycle Trader magazine and a raft of documents kept at the British National Archives. “I don’t think any other historian of the British motorcycle industry is aware of these sources, never mind used them in a book on the subject,” Koerner says. Indeed, 67 pages of the total 350 in The Strange Death of the British Motor Cycle Industry include detailed notes and references.

“I haven’t spent a day of my life working in a factory or motorcycle retail environment,” Koerner says. “But I think I bring a different perspective to the (British motorcycle industry). It’s a business history when you get right down to it.”

Photo copyright Steve Koerner. In the B.C. Kootenays with his 1977 Triumph Bonneville sometime in 1978.

In Koerner’s ideal transportation world everyone would drive an Austin Cambridge or ride a Matchless G80, and he remains a devout fan of British motor products. That’s because Vancouver Island in the 1950s and 1960s was a different place. Ties to old Britannia were evident, and the corridor between Victoria and Cowichan Valley teemed with British motor products.

Born into this Canadian microcosm of British culture, Koerner became immersed in English vehicles. Apart from a couple of Chevrolets, his parents drove mainly British cars, including a Hillman Minx, a Humber Super Snipe and a Jaguar XJ6. “British vehicles have always been a part of the family, and remain so to this day,” he says.

An avid motorcyclist, Koerner rode a 1970 B.S.A. Thunderbolt around Vancouver from 1976 to 1978. “It was a vile beast,” he recalls, but that experience didn’t prevent him from owning a string of Brit-bikes, including a new 1977 Triumph Bonneville. He shipped the Triumph to England, riding to the TT races and visiting the Meriden Triumph factory in 1979.

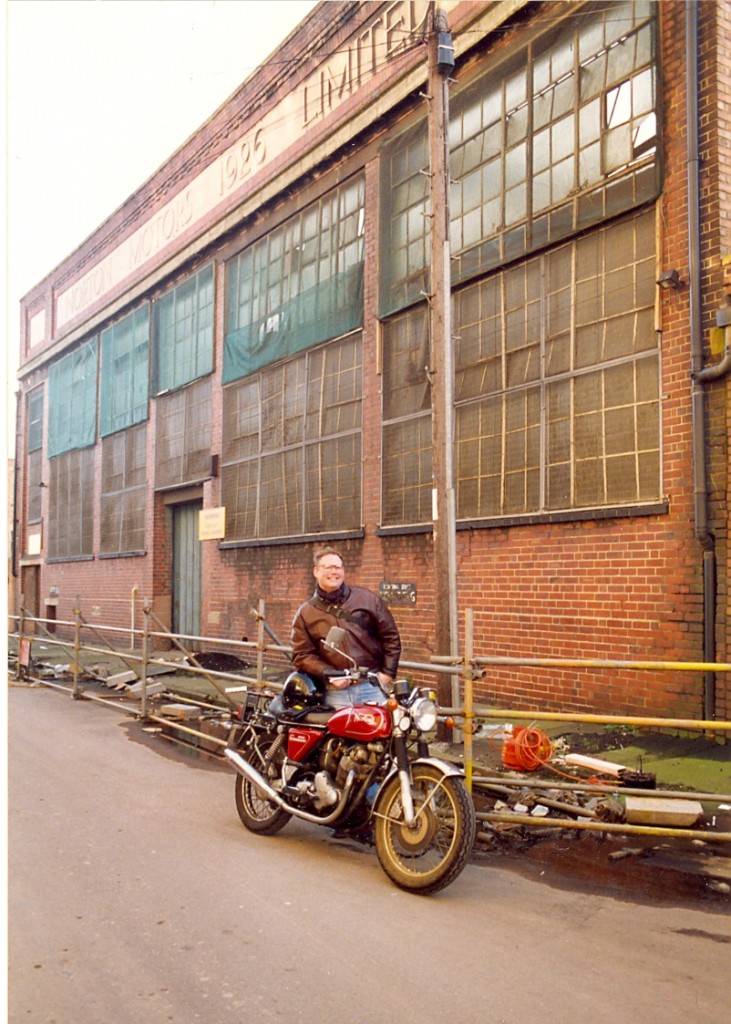

Photo by Jurgen Pokrandt. Of his ride, Koerner says: “My Norton originally came out of the factory as a 1974 Roadster model with a red-coloured tank. Several years ago I changed it over to an Interstate model with a used tank (metal and factory original) and seat (both of which I found via the Norton Owners’ Club in Britain) along with new side-panels which come from Fair-Spares in Burnt Bridge near Birmingham. The tank is painted traditional Norton silver-grey. No, I realise the paint scheme is not correct for 1974 but I think it looks pretty good, despite, no doubt, objections from the purists.”

He currently owns a 1974 Norton Commando Mk. IIA Roadster, which he’s converted to Interstate specification. There’s also a 1958 Matchless G80 in the shed. However, the bike he now rides most is a Harley-Davidson Road King.

Koerner is as much a British motorcycle enthusiast as he is an academic, but he doesn’t wax nostalgic about the industry. He is critical in hindsight, and although players in the trade aren’t identified as heroes or villains, it’s fairly obvious who they are.

Courtesy Steve Koerner. This is the same Norton seen in the previous photo, and was taken at the Bracebridge Street factory in the early 1990s.

Managing director of Ariel and Triumph and later chairman of BSA, Jack Sangster, is a hero. “He was competent and successful,” Koerner says of Sangster. “I think he came out of the womb on a motorcycle, and he was effectively a talent scout, hiring Edward Turner and Val Page.”

Bernard Docker, chairman and managing director of B.S.A. from the late 1940s to 1956, is a villain. Koerner describes him as ‘inept and scandal-prone’.

B.S.A. was a massive company, with several divisions including Daimler – a low-production luxury limousine maker. Docker wanted the firm to break into the far more competitive middle class car sector, which in the 1950s was largely dominated by Humber, Jaguar and Rover. Moving Daimler downscale was a high-risk strategy, poorly conceived and executed with millions of pounds wasted. The results almost destroyed both Daimler and its parent B.S.A.

“If only a small amount of money had gone into motorcycles instead of cars,” Koerner says. “B.S.A. never recovered from drowning in red ink, and when Sangster took over he had to sell off assets to keep the company liquid.”

Koerner investigates many facets of the British industry, which seems to have built itself into a corner after the Second World War as it supplied mainly sporting motorcycles to a young, male dominated crowd. But the industry had tried post-1918 to design and market an ‘Everyman’ motorcycle, one that would appeal to a broader audience, including women. The scooter was the answer.

Many of these new products were either designed or built by the aviation industry (after the First World War, airplane manufacturers were looking to expand their markets and utilize their manufacturing capabilities). Vehicles such as the Skootamota and the Reynolds Runabout, and even the Ner-A-Car, which was engineered by an American but first built in Britain, couldn’t find traction.

Of the machines produced, Koerner says, “(I think) these British scooters failed because, although often innovative in concept, they were undermined by poor design work and engineering. I suspect the companies which made them just didn’t have enough experience in making motorcycles/scooters to make a success of it.”

Photo copyright Steve Koerner. This assembly line image was taken in June 1979.

Crippled by the early 1970s there is no easy answer regarding the downfall of the British industry, but Koerner’s book is one of the better attempts at an in-depth exploration. “Life is complicated,” Koerner says. “And there aren’t simple explanations. It wasn’t all Bernard Docker’s fault, nor was it German or Japanese manufacturers, or the attitude of management. It’s simply not that simple to explain.”