Pete Young of Occhio Lungo: Revealed

I penned my most recent Cycle Canada New Old Stock column about Pete Young, proprietor of the Occhio Lungo blog. His site is dedicated to everything old motorcycle, leaning heavily towards the veteran era (but not always!). Plenty of interesting posts on Occhio Lungo.

In preparation for the column I drafted a list of questions, and Pete more than generously answered each one of them, in detail. I could use only a very small portion of our exchange in my 750-word column, but his answers are simply too good to waste. Here is the full dissertation.

All images are courtesy Pete Young and Occhio Lungo.

1. How did you first get interested in motorcycles, and what was your first machine?

I grew up in the desert of Eastern Washington, and my dad bought me a Honda ATC 110 for my tenth Christmas. I’ve been riding bikes ever since. I’m 42 now, so that is 32 years on bikes. The first bike that I bought with my own money was a 1972 CL 350. My friends and I wanted to make café racer bikes, but Tritons and BSA’s were too expensive. I know that resonates with a lot of guys today, but this was in the 1980s! Then, as now, 70’s Japanese bikes were an affordable way to play around.

2. Where did you learn to be so self-sufficient with tools? Did you have a mentor, or are you self-taught?

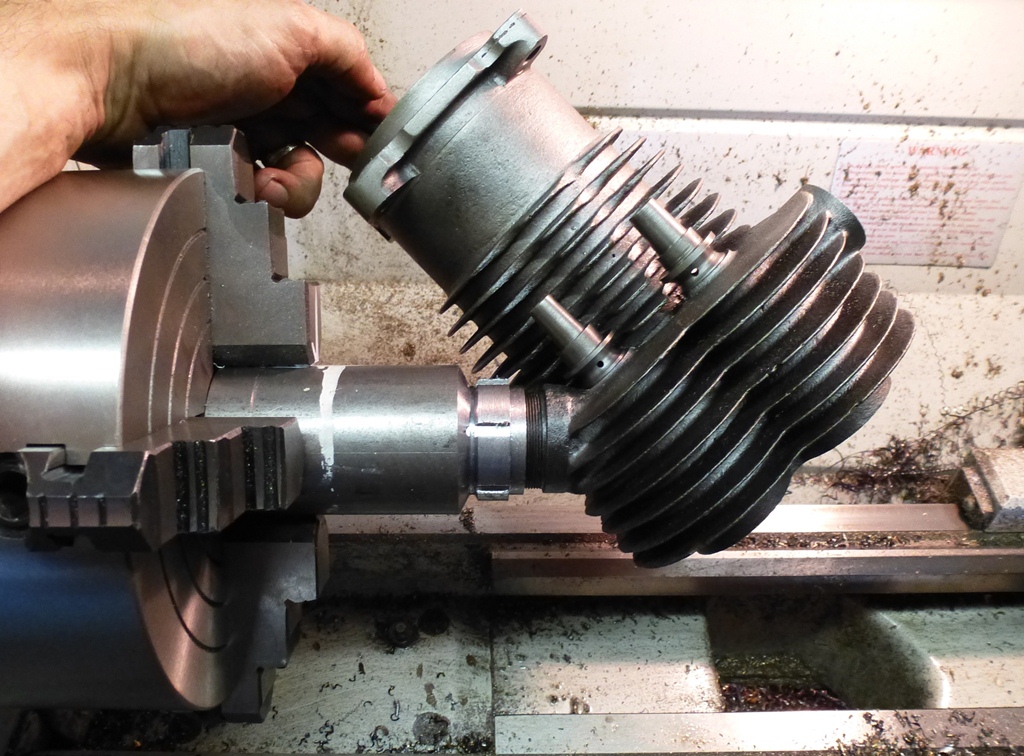

In the old days (ha!) kids like me took metalshop class in ninth grade. I loved that class, and learned the basics of running a Bridgeport mill, a lathe, stick welding, etc. My dad had taught me how to spin wrenches already, as we restored a 67 Camaro as a father and son thing. He was very self-sufficient, and taught me about plumbing, wiring, how to swing a framing hammer, how to lay sod, and many other things like that. When I went to college to learn engineering, I took a part time job as a machinist helper / engineering technician at a supplier to Boeing. I was responsible for some very basic design tasks, and to fabricate some parts from my drawings or from those of the staff engineers. The shop foreman was a kind and patient man, and he let me burn a lot of hours doing setups and scrapping a few parts before I got one that passed inspection.

3. How does your engineering background inform your motorcycle hobby?

I’m lucky in that I get paid to do something that I would do just for fun. Bearings, linkages, and castings occupy my thoughts all day, whether I’m on the clock for a client or thinking about a motorbike or car. My background in engineering design has shown me a lot about manufacturing processes. Not just the typical machine shop stuff, but also waterjet or laser cutting, rapid prototyping, sheetmetal tooling and other fun stuff. And I’ve worked with some great shops and vendors across America and a few in Asia too. All of that has helped me to understand that restoring a bike, or building a bike from scratch is not as hard as it appears to be. Men did this work 100 years ago with tools that are primitive compared to what we have today. They did it without carbide tools, or TIG welding or alloy steels and often without a high school education. Surely we can try to emulate, or maybe equal, their efforts?

4. When did you get your first Velocette, and what drew you to that particular make?

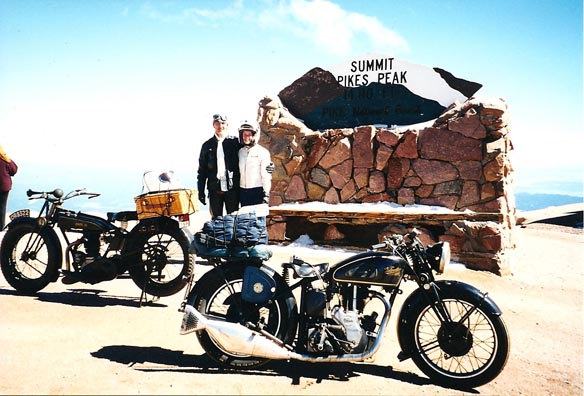

During the 1990s I began to look further back into the past, beyond the 1970s bikes that had excited me until then. The pre WWII Velocettes were striking, painted black with gold trim and bright chrome fishtail mufflers. The girder forks and rigid frames looked very purposeful, and the racing pedigree of the KTT and Thruxton bikes was impressive. But since I began studying the Veloce company and their bikes, I’ve grown to like them more for their engineering and inventions. They created so many things that we use on bikes today: positive stop foot shifters, the dual seat, adjustable rear suspension, etc. They are good riding bikes, and their owners tend to use them. In 15+ years, we’ve ridden our MSS for thousands of miles, and my wife Kim has also ridden her 1930 KSS (350cc OHC) all over the western USA and Canada. Older and older bikes grab my eye each year and now I’m finishing up the restoration of a 1913 Veloce now, which has been a big two year project.

5. What machines grace your garage?

We have just over a half-dozen machines in total, mostly Brit single cylinder bikes from the 19teens, 20’s and 30’s. I also play around with one American bike, a 1916 Excelsior twin. The 1938 MSS has remained our most “modern” bike for the last 20 years or so.

6. You’re not a collector who hoards your machines – together with your wife and children, you ride them. Those experiences set you and your family apart – does it also bring your family closer together?

Machines are for riding, it is as simple as that, just as ovens are for baking, and boots are made for walking. Static machines in a museum are nice to see, but they really come alive when filled with fluids and fired up to make noises and cut a good line on a curvy road.

Kim and I rode together for years before we had children, and decided that we didn’t want to stop once they arrived. So I found a Dusting sidecar for the Velo MSS when she was still pregnant, and fitted it to my Velo and waited for the baby to arrive. (Kim made me wait until each kid was about 8-9 months old before they could ride in the chair…). What was the question? Oh yeah, family. We love riding together, seeing the backroads, stopping for ice cream, pointing at the deer or hawks that we spot from the bike. It can be a great educational experience too, stopping to see and explore caves, or learning about the Gold Rush and the mines, the geology of places like Glacier Natl. Park or Mt. Lassen. The kids are still relatively small, aged 8 and 10, so they tire of riding on the back of rigid bikes after several hours. Frequent stops and some pep talks help us to keep going on the 5 day rallies.

7. Do you encourage your kids to help out in the shop?

I do, but at their age it is still hard for them. Welding and grinding doesn’t excite them as much as dolls and video games. But I try not to force it, and ask them to do some fun things like painting or assembling the newly plated parts. They have been more excited lately as I’ve gotten their help to set up pillion seats footpegs on some of the bikes for them to enjoy.

8. Your shop; is it a standard double car, or single, or? What kind of tools do you have in there?

Years ago we found a dilapidated old Victorian home that featured a three car garage and some space for a workshop. It was love at first sight. The shop has a lot of the typical tools for our hobby like a good lathe, welders, grinders, etc. A table top mill has been very helpful, and a lot of random things like a tubing bender, hydraulic press and an assortment of hammers.

9. You took part in the first Cannonball run – were you prepared for the challenge?

Ha! That’s a good question. It seemed that I was, but the C’ball is a tough event. I prepped for a year, and brought my 1913 Premier and also my Excelsior as a backup. (We didn’t realize how strict the rules were going to be until we arrived at the start, and the X wasn’t allowed). In addition to prepping two bikes, I took up jogging 4 days a week and tried to eat healthy. Anyway, I had ridden the Premier for several years before the C’ball, and it was in good shape. But the crankpin broke on the first day. It took a lot of effort to tear down the bike, find a shop at midnight, make new parts, install them and get back on the road. I missed a day and a half of the Cannonball due to that, and several other half days for breakages like the V belt pulley. 98 year old steel can and does fail due to fatigue, but I cannot complain. That’s just the nature of the old bike game. I was stubbornly determined to ride the bike across the USA and to the finish, and that is exactly what I did. On the last day, the motor seized after the oil sump drain let the oil escape. There was still about 100 miles left in the day, so I poured a quart of oil into the spark plug hole, rocked the bike back and forth and freed up the piston. Then I rode it carefully to the pier in Santa Monica and drank a very cold beer. It was the best beer I’d had in a very long time.

10. The Veloce that you’ve most recently finished, I believe, is intended to be ridden in the 2013 Pioneer Run in the U.K. What encouraged you to enter?

Knowing that the bike was to be 100 years old, Dave Masters invited me to join him on the Pioneer Run from London to Brighton. Dave is a Velo fellow and plans to ride his own 1912 i.o.e. Velo. So we made plans for me to finish the bike, and ship it to England. We’ll celebrate the bike’s 100th birthday with cake and ice cream at the finish in Brighton. It is terribly silly and expensive, but that is what credit cards were made for. Besides, I won’t be here for the bike’s 200th birthday. (Update: the cylinder base on the Veloce cracked while break-in miles were being added, scuppering the plans to attend the Pioneer Run. Ironically, the 2013 Pioneer Run was cancelled due to snow …)

11. Why did you decide to start blogging about vintage motorcycles and the technology (or technologies) that were first being tried? You’re shining a light on the fact that most of what we’re seeing on today’s machines has, at one time or another, already been tried.

Thanks, I’m glad that you like reading Occhio Lungo. It is exciting to see how engineers and designers solved the same set of problems 100+ years ago: How to carry a person on a motorized bicycle or car. Each designer tried their best, but of course there were many possible solutions and many of them didn’t work as well as others. But as you mentioned, there were great things done before WWI, such as disc brakes, water-cooled two strokes, electric, steam, gasoline power and also hybrids, mono shock rear suspensions, telescoping front forks, transverse four cylinder motors, shaft drive, OHC, etc. The marques that failed often had the most innovation. It all fascinates me, and I wanted to share my fun with readers from around the world. I never expected more than a dozen people to read it, but it has surprisingly found an audience of hundreds of people per day. The message is supposed to be about the fun of studying old technology, coupled with the joy of riding early machines, and the How To articles that show repairs and fabrication in the workshop.

12. How much has the computer and social media changed your perspective on vintage motorcycles and the hobby in general?

Over the past three years, I’ve become friends with people from places like Tasmania, the Czech Republic, Latvia, quiet corners of Ireland, Spain and France and so many other places. Email, Facebook and blogs/websites have opened up the communication to so many far flung locales. There are only a few people in San Francisco who don’t get bored talking about veteran and pioneer machines. But across the globe there are plenty of guys who want to chat, share tuning tips, trade parts, etc. And as a research tool, the internet is better than any library that I can find. When searching for documentation on a specific model of machine from 100 years ago, sometimes only one person or library has a manufacturer’s brochure. But scanning it and posting it to a web page, or emailing it around the world has become so very simple. After looking around for a year via the computer, I had contacted people in clubs and accessed private libraries, and had amassed more information about 1913 Veloce motorcycles than anybody had possessed since 1913. (That sounds like a lot, but it is really just some old adverts and a few period photos). Still, that information allowed me to know what the bike should look like when I restored it. That was impossible just 20 years ago. If we do it right, our restorations today can be much more correct than those done in previous generations.