The Osborn Engineering Company, or O.E.C.

With many thanks to Martin Shelley, marque expert, and Bill Wood, editor of the Antique Motorcycle Magazine. First published as a two-part Pulp Non-Fiction column in the Antique Motorcycle Magazine (Nov./Dec. 2017 and Jan./Feb. 2018), this is intended to be as comprehensive a history of O.E.C. as possible, and, according to Shelley, helps dispel a number of inaccuracies in other online O.E.C. stories. Click any image in this story to enlarge.

There are many fascinating threads to the story of the Osborn Engineering Company, or O.E.C. First, we’ll tackle the company’s early era, which led to a number of world land-speed records. Then, we’ll pick up with the innovative and sometimes strange machines that followed.

My own interest in O.E.C. began as a result of two pieces of the company’s literature in my collection, both from the mid-1930s. My research into those items led me to Martin Shelley of the Vintage Motor Cycle Club in the United Kingdom, who is a marque specialist in O.E.C. and Blackburne machines. He provided many notes and details about the O.E.C. company that I would not have learned otherwise.

The interesting tale of O.E.C. starts with the company’s namesake, Frederick J. Osborn, who lived in Hampshire County, along the southern coast of England adjacent to the Isle of Wight.

According to author Ralph Venables, writing in a March 1973 article in the Gosport Records, a publication in one of Hampshire’s port cities, F.J. Osborn was a successful high-wheel or “penny farthing” racing bicyclist. But at the dawn of the 20th century, he began producing what Venables refers to as “motorized Bath-chairs.” A Bath chair, so named because they were purportedly invented in the British city of Bath, was a three- or four-wheel device used to carry the disabled. These appear to have been rudimentary motorized wheelchairs featuring an internal-combustion power source, although there is little evidence about their exact nature.

What is clear is that in 1901, Osborn constructed a one-off motorcycle for track racing with a 4-horsepower (approximately 500cc) Auto-Moto engine clipped to the front downtube of a lightweight cycle frame.

Apparently, this did not lead to further motorcycle production. In fact, there is nothing to indicate Osborn was engaged in anything else to do with vehicles between 1901 and the end of World War I.

(One source maintains that Osborn’s O.E.C. company produced four-speed engine crankshaft pulleys, but that, according to Shelley, was a different man, named Osborne with an “e.” The similar names have led to confusion by researchers, and Frederick’s last name is often misspelled with an “e” on the end.)

Venables wrote that it was around 1919 when Osborn joined forces with engineer Frederick Wood, and they acquired the use of a defunct factory for military aircraft in Lees Lane, Gosport, where they intended to manufacture motorcycles.

The factory was soon taking on motorcycle repair work, fabricating frames and tanks, and also building complete motorcycles for Burney & Blackburne, a separate motorcycle company that plays an important part in the O.E.C. story.

According to Shelley, brothers Alick and Cecil Burney were apprenticed to a prominent engineering enterprise called Willans & Robinson. In 1919, this company became known as English Electric.

While employed at Willans & Robinson, the Burneys worked with a number of other apprentice engineers who would become famous in their own right, including Geoffrey de Havilland, founder of De Havilland Aircraft, along with Archie Frazer Nash and Ron Godfrey, who made the GN cyclecar, plus the Frazer Nash and HRG automobiles.

When de Havilland left to pursue his interest in aviation, the Burneys persuaded him to sell them the rights to manufacture copies of a motorcycle engine he had designed. They acquired de Havilland’s castings and drawings for the sum of 5 pounds.

The Burneys initially built two machines for their own use and competed successfully in many early motorcycle events up to 1910. In 1912, Shelley notes, de Havilland’s friend and fellow aviator, Captain Harold Blackburn, agreed to put up 200 pounds in capital to start a motorcycle company that would be known as Burney & Blackburn Ltd.

Soon after, Burney & Blackburne (which somehow gained an “e” at the end) was making a name for itself building high-quality motorcycles that won praise when tested by The Motor Cycle magazine in 1913. But when Britain went to war with Germany in August 1914, the War Office realized the army needed competent motorcyclists to act as despatch riders, so they hastily recruited suitable candidates, including the Burney brothers and their fellow Burney & Blackburne directors, brothers Cecil and Allan Roberts.

Most of O.E.C.’s earliest machines, such as this 1925 350cc model, were powered by engines from Burney & Blackburne. Eventually, the company would source powerplants from a variety of manufacturers. Photo courtesy Martin Shelley.

All these young men went to France with their prototype Blackburne machines, leaving the Roberts brothers’ father to run their company.

Burney & Blackburne continued to produce a small number of motorcycles, along with other war-related equipment. But by 1919, it was clear that the company was more interested in building engines, rather than complete motorcycles. To do this, they engaged the services of F.J. Osborn’s son, John Osborn, who was a friend of the Burney & Blackburne’s managing director, Stanton Wilding Cole. His Osborn Engineering Company took over responsibility for assembling the Blackburne motorcycle, while Blackburne just supplied the engines.

“Thereafter,” Shelley writes in his recently published book, “Two Wheels to War,” “Blackburne concentrated on the manufacture of air-cooled sporting engines for motorcycles and other applications. Blackburne engines were fitted to many vehicles, including boats, light cars, aeroplanes, and even lawnmowers.”

So the birth of O.E.C. as a motorcycle manufacturer in its own right happened almost unannounced, when a line of Blackburne machines was exhibited at a motorcycle show in November 1922 on a stand bearing the name “O.E.C.-Blackburne.”

Those machines were powered by Blackburne 2¾- and 4½-horsepower single-cylinder overhead-valve and side-valve engines. There was also an 8-horsepower side-valve V-twin machine, and all were available in Tourist and Sports versions.

A circa-1923 trade leaflet claimed, “The Famous Blackburne Motor Cycles which we manufactured for four years are now known as O.E.C.-Blackburne, ‘The Machine that runs like a car.’ ”

Before that, however, O.E.C. was already pioneering unusual variants on the motorcycle theme that would result in suggestions by some that its initials actually stood for Odd Engineering Contraptions.

The first of these, introduced in 1921, was called the Sidecar Taxi. This consisted of an enclosed sidecar attached to a 10-horsepower side-valve V-twin Blackburne motorcycle. But instead of handlebars, the machine had a novel worm-drive steering wheel. This was the first machine openly described as an O.E.C.-Blackburne.

O.E.C. continued to use Blackburne engines, including the company’s increasingly popular overhead-valve, exposed-flywheel designs that had seen much racing success in the Isle of Man TT and at the Brooklands racetrack in England. However, the company also began to offer motorcycles powered by a variety of other engines—what “Grace’s Guide to British Industrial History” refers to as “combination models.” These included O.E.C.-Atlanta and O.E.C.-Anzani bikes. Mostly, these were simply labeled as O.E.C. machines, even though some were still offered with Blackburne engines.

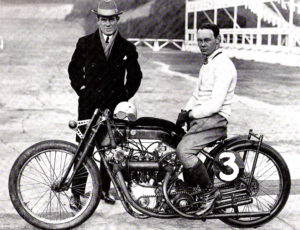

A record breaker: Claude Temple aboard the O.E.C. machine, powered by an Anzani overhead-cam engine, that set a land-speed record of 108.48 mph at the British Brooklands racetrack in 1923. With him is Hubert Hagens, designer of the engine for the British branch of Anzani.

The next impressive figure who crops up in the O.E.C. story is Claude Temple, a British speed enthusiast well known for campaigning machines designed to set land-speed records. Temple’s first connection with O.E.C. came as a result of his association with Hubert Hagens, the engineer behind a 1,000cc overhead-cam V-twin built by the British branch of the French Anzani Moteurs d’Aviation.

O.E.C. took this engine and installed it in a duplex loop motorcycle frame, making a bike known as the O.E.C.-Temple-Anzani. This machine set a world speed record of 108.48 mph at Brooklands in 1923.

The bike was constructed from steel tubes, soft-soldered together using lugs. The frame components were copper plated to facilitate the soldering process, and having survived its competition career, this historic machine was unfortunately incinerated in the disastrous 2003 fire at the British National Motorcycle Museum. The unique land-speed racer was reduced to a pile of twisted tubes and molten aluminum on the museum floor.

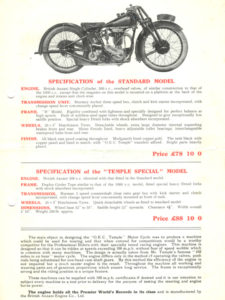

Shelley says the company continued to pursue speed records through the 1920s, setting five records in September 1925 at the newly opened Autodrome de Montlhéry, south of Paris. Of those, the company was proudest of the fact that an O.E.C.-Temple machine completed 102 miles in a full hour of running.

“This is the first time in the history of motor-cycling that a motor cycle has been officially timed to cover 100 miles in the hour,” the company proudly stated.

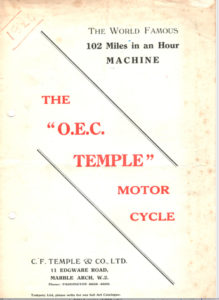

That claim came in a circa-1926 brochure promoting a line of high-performance motorcycles representing a collaboration between Temple and O.E.C.

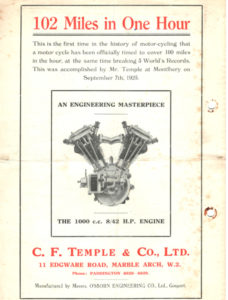

The collaboration between O.E.C. and Claude Temple sparked the development of a separate brand of production motorcycles, known as O.E.C.-Temple. A brochure for 1926 introduces the company’s high-performance 1,000cc V-twin and 500cc single-cylinder machines, derived from the bike that set a one-hour record of 102 mph the previous September on a racetrack in Montlhéry, France. Brochure courtesy of Martin Shelley.

“The main object in designing the ‘O.E.C. Temple’ Motor Cycle,” the brochure states, “was to produce a machine which could be used for touring and that when entered for competitions would be a worthy competitor for the Professional Riders with their specially tuned racing engines.

“This machine is designed so that it can be ridden at speeds exceeding 100 m.p.h. without fear of speed wobble which is common with many machines. The design is actually taken from Mr. Temples’ famous ‘102 miles an hour’ motor cycle. The engine differs only in the method of operating the valves, push rods being substituted for overhead cam shaft gears.”

Production versions of the Anzani-powered ‘O.E.C.-Temple’ machines were offered in 1,000cc V-twin and 500cc single-cylinder configurations. But they did not prove very popular with buyers, and the brand lasted only a couple of years.

A year later, Temple and O.E.C. were back in France, this time running their bike on a closed stretch of public road just south of Montlhéry in Arpajon. The result was a land-speed record of 121.44 mph, eclipsing a mark of 118.99 mph set by Bert LaVack on a Brough Superior machine on the same road in 1924.

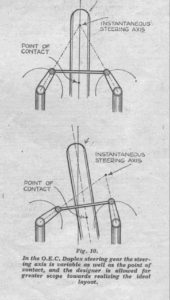

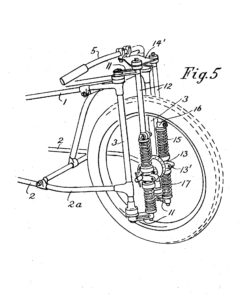

A patent drawing (right) shows the unique Duplex Steering system devised by O.E.C. engineer Frederick Wood. A separate technical drawing (left) reveals the complex geometry behind the design. Theoretically, the system offered outstanding high-speed stability and adjustability. In practice, it was better suited for use on a speed-record machine going in a straight line than on a road motorcycle. Items courtesy of Martin Shelley.

Meanwhile, O.E.C. continued experimenting with alternative front-end designs for its motorcycles. In 1927, the company was granted a patent for its unique Duplex Steering system, devised by Frederick Wood. It is unlikely you’ve ever seen anything like this system, which is described this way on the Sinlesscycles.com website: “[T]he ‘Duplex’ steering system (not really ‘forks’), [was] a visually complicated assembly of parallel tubes. The extended front tubes make for an extremely stiff frame, and very stable steering…almost too stable in fact, as the Duplex system could never be credited with being nimble. At speed, the Duplex prefers to self-straighten, meaning it’s incredibly stable, if not particularly agile for corner-carving.”

The bike involved in O.E.C.’s final land-speed record was powered by a supercharged 1,000cc engine from J.A. Prestwich Industries. The frame incorporated O.E.C.’s Duplex Steering design. On November 6, 1930, rider Joe Wright set a record of 150.74-mph record in Cork, Ireland, using this bike for his first run, and a Zenith frame with a similar engine for the return run.

That high-speed stability may not have made this a great steering design for a road motorcycle, but it was ideally suited for a land-speed machine. And in 1929, Temple commissioned O.E.C. to construct a Duplex Steering chassis fitted with a 996cc overhead valve, V-twin engine from J.A. Prestwich Industries. With Joe Wright at the controls, that bike ran 137.23 mph at Arpajon in August 1930, briefly retaking the world speed record from Ernst Henne, who had set a mark of 134.67 mph the previous year aboard a supercharged BMW.

Less than a month later, Henne and BMW retook the title with a speed of 137.74 mph. But Wright easily surpassed Henne’s run with a speed of 150.74 mph in Cork, Ireland, on November 6, aboard a supercharged bike.

That flurry of runs saw the land-speed record broken three times in less than 10 weeks! But Wright’s 150-mph run became the subject of controversy when it was later determined that he ran the O.E.C.-framed machine only in one direction. When he made the required return run, he instead rode a Zenith motorcycle with a similar engine and transmission—effectively, O.E.C.’s spare bike. Still, the run was certified, and the record would stand until Henne reclaimed it in 1932, and kept raising it until his run of 173.68 mph in 1937.

After that run, the company would never again have a claim to the world motorcycle land-speed record. But that didn’t bring an end to O.E.C.’s tradition of innovative, unusual and just plain odd design. If anything, the company was only getting started in that area.

Indeed, author Ralph Venables made note of the company’s tendency to pursue its own engineering vision in a March 1973 article in the Gosport Records, a publication in the area around Portsmouth, England, where the company had been based decades earlier.

“Both [founder F.J.] Osborn and [engineer Fredrick] Wood were men of exceptional ingenuity blessed with inventive brains from which emerged many brilliant ideas,” Venables wrote. “These two-wheelers (and occasionally three-wheelers) took their place in history as among the most unorthodox machines to have come from any British factory.”

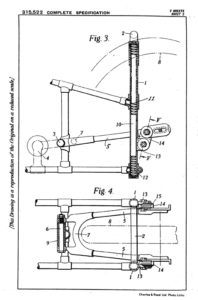

This patent drawing shows the functioning of the O.E.C. Rear Springing system. The ends of the rear frame pieces ride on springs in vertical tubes, while the rear wheel is attached to a pivoting swingarm. Courtesy of Martin Shelley.

O.E.C.’s 1933 product line included this 250cc overhead-valve model OHV, powered by a single-cylinder J.A.P. engine. Although it appears conventional in most respects, the bike is notable for the company’s proprietary Rear Springing system, combining elements of plunger and swingarm suspension. Brochure courtesy of Martin Shelley.

Some of O.E.C.’s engineering concepts truly were ahead of their time. In 1929, the company developed an experimental machine powered by a novel water-cooled “engine in a box” that was entered in the 1929 Isle of Man TT. The bike failed to qualify, and O.E.C. employee George Williams explained the problem in the Venables story: “It was just too ambitious. Too unorthodox to find real favour with a conservative public. Fred Wood’s ideas were far ahead of their time, and we lacked sufficient funds to do them justice.”

Martin Shelley points to another example of the company’s ahead-of-its-time innovation. In 1933, he notes, O.E.C. pioneered the use of all-welded tubular-steel frames.

At the time, nearly all motorcycle frames consisted of cylindrical steel tubes brazed together using cast lugs at the junction points—the steering head, the bottom end, etc. O.E.C.’s decision to begin welding its frame tubes directly to each other may not have seemed noteworthy back then, Shelley says. But, helped by advances in metallurgy and manufacturing techniques after World War II, direct welding would eventually become the norm throughout the industry.

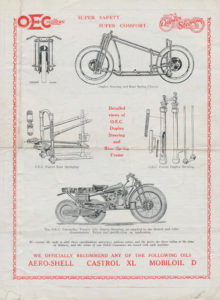

Shelley adds that O.E.C. was also unusual among smaller motorcycle manufacturers in producing well-illustrated sales leaflets and catalogs, as the company clearly believed in the value of marketing. And this brings me to the two pieces of O.E.C. literature in my own collection. These items, from 1933 and 1934, serve to illustrate some of the company’s other unique technology.

One is a single-sided page promoting the 1933 O.E.C. 250cc OHV, powered by a single-cylinder J.A.P. engine (with Rudge or Blackburne powerplants available as upgrades). In most respects, the machine looks like other British motorcycles of the era, but it incorporates a Rear Springing system patented by Frederick Wood that is a bit like a cross between plunger rear suspension and a swingarm. The plunger-style springs are carried in vertical tubes connecting the upper and lower rear frame rails. But the wheel is attached to a swingarm that pivots on an axis near the base of the seat tube.

“The Rear Springing system,” the brochure notes, “is the only type in which the whole motorcycle is fully sprung, thus insulating the rider and pillion passenger from all road shocks.”

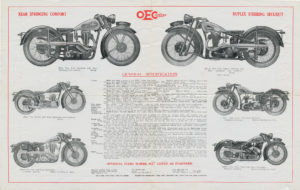

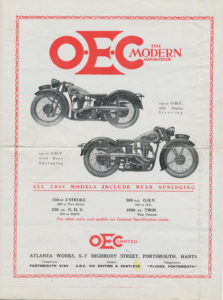

For 1934, O.E.C. offered models ranging from 150cc two-stroke singles up to 1,000cc four-stroke V-twins. All bikes came with the company’s Rear Springing system, and buyers could choose between standard girder forks or the O.E.C.’s innovative Duplex Steering front end. Brochure courtesy of Martin Shelley.

The 1934 brochure is a two-page piece that folds out to display the entire O.E.C. line. The machines offered ranged from 148cc and 250cc Villiers-powered two-strokes to 250cc, 350cc and 500cc four-stroke singles using the company’s own engines. There’s also a 1,000cc O.E.C. side-valve V-twin.

All of the bikes use the company’s Rear Springing system, and a couple also incorporate the pioneering Duplex Steering system used on the final generation of O.E.C.’s speed-record bikes (see the November/December issue for a description of this highly stable, but not-so-maneuverable, alternative to girder or telescopic front forks).

“No expense has been spared,” the brochure proclaims, “in the design and production of the frame and springing, which are unrivalled as regards quality in design and performance.

“The world famous O.E.C. Duplex Steering frame or chassis, designed with the well-known exclusive features of extraordinary stability and comfort, is now supplied as an optional item…The long duplex steering heads and enclosed springing movement, together with the inherent stability of the design layout, provide a machine giving extreme comfort and safety which can be ridden with confidence under all conditions, and due to the self-centreing action of the duplex steering in combination with the rear springing, is far less tiring on long journeys for both rider and passenger.”

In a bid to demonstrate the superiority of Duplex Steering over conventional girder forks, O.E.C. entered four racing machines in the 1934 Isle of Man TT. The factory team included one 250cc machine with a girder fork and one with its Duplex Steering system for the Lightweight TT, and a similar pair of 500s for the Senior TT. Unfortunately, the demonstration failed when none of the bikes completed their races.

Besides more-traditional motorcycles, O.E.C.’s 1934 offerings included the Caterpillar Tractor, an unusual three-wheeled machine developed from this bike, built for testing by the British Army. Note the tank-style track strapped to the luggage rack, which could be affixed around the rear wheels for greater traction on soft surfaces. Courtesy of Martin Shelley.

The back of the ’34 brochure, meanwhile, highlights a machine that takes motorcycle design in another direction entirely—the O.E.C. “Caterpillar Tractor.”

Developed in 1929 to meet a new military specification for off-road use, this is a three-wheeled motorcycle. But instead of having its dual rear wheels arranged side by side, like a tricycle, they are placed one in front of the other, mounted on a pivoting trunnion, rather like the “truck” that carries the wheels on a railroad car.

Ground clearance was an impressive 12 inches, and the company said that a tank-style track could be fitted to the rear wheels for use on soft ground. Unfortunately, like so many of O.E.C.’s innovations, the Caterpillar Tractor was not a conspicuous success. The British Army’s trial report indicated that it was almost unrideable on anything other than loose surfaces, with a propensity to go straight ahead even when the bars were turned. There is no evidence of mass production beyond three prototypes, and the only remnants that survive consist of parts of one, powered by a 350cc side-valve Blackburne engine, in Shelley’s collection.

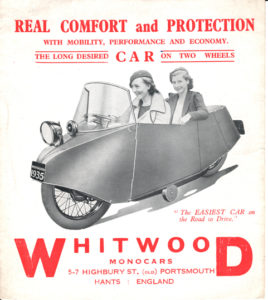

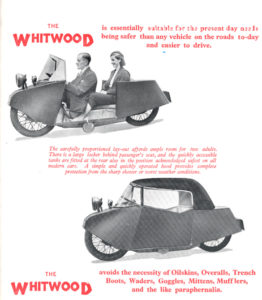

“The Long Desired Car on Two Wheels.” That’s how O.E.C. marketed the Whitwood, an enclosed motorcycle with the driver and passenger seated low between the wheels. Options included side windows and even a convertible roof. Brochure courtesy of Martin Shelley.

The Caterpillar Tractor looks downright normal in comparison to the Whitwood, another O.E.C. machine of the same era. Shelley graciously shared a 1935 brochure that describes the Whitwood as “The Long Desired Car On Two Wheels.” It is, in fact, basically a stretched motorcycle frame covered by a sidecar-like body, with the driver and passenger seated one behind the other between the wheels. The engine was mounted just behind the passenger seat, with the cylinder angled backwards, alongside the rear wheel.

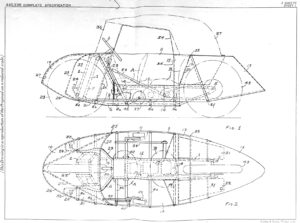

This patent drawing for the Whitwood shows the location of various components. The single-cylinder engine is sketched in with the crankcase behind the rear seat and the cylinder angled backward, next to the rear wheel.

This monocar was marketed as a low-cost alternative to a four-wheel automobile, with doors, a windshield and even side windows and a convertible roof on some models. Directional control was accomplished through a steering wheel instead of handlebars, and outrigger wheels stabilized the machine when stopped.

Models ranged from the 150cc two-stroke Dart and 250cc two-stroke Sterling to the 500cc side-valve Century and 1,000cc side-valve V-twin Regent. All models came with seating for two, but they could be extended to take another passenger as an extra-cost option.

The company’s copywriters promoted the Whitwood as a revolution in personal transportation, saying that this two-wheeled auto was “the EASIEST CAR on the Road to Drive.”

“The Whitwood conquers Stuffiness, Fumes, Spills, Skids, Kick and Push Starting, Footing, Traffic Crawls and Winter Lay-ups,” the brochure promised, adding that the engine options would bring “the Joy of Luxurious Private Road Travel to all classes in the wide range of Models offered.”

Perhaps to distance the machine from the motorcycle world, the O.E.C. name appeared nowhere on the promotional materials. Instead, the Whitwood brand was created by combining the names of the vehicle’s inventor, Fred Wood, and company director E.H. White.

Alas, the Whitwood Monocar did not live up to the advertising hype. No production models are known to exist, although there are rumors that a prototype has survived.

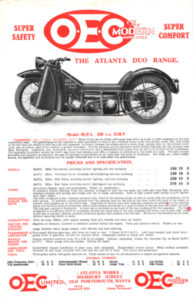

The 1936 O.E.C. Atlanta Duo was based on the same low-slung, feet-forward seating position of the Whitwood, minus the bodywork. Engines ranged from a 250cc two-stroke to a 750cc side-valve V-twin four-stroke. Brochure courtesy of Martin Shelley.

For 1936, O.E.C. took the Whitwood concept, removed the bodywork, and tried to sell a low-slung, “feet forward” motorcycle called the Atlanta Duo that is highlighted in a 1936 brochure, again courtesy of Shelley. The look is similar to the Ner-A-Car, developed by American Carl Neracher in the 1910s and eventually made in the U.S. and in Great Britain. The final Ner-A-Cars were made in the late ’20s, nearly a decade before O.E.C. introduced the Atlanta Duo, which it marketed as “The Modern Motorcycle.”

“The O.E.C. Atlanta Duo Motor Cycle can be ridden with equal ease either as a solo or with passenger on the long comfortable seat,” the brochure says. “The performance of the machine is quite equivalent to that of any orthodox motor cycle with similar power unit, and owing to the fact that the weight of both the rider and passenger is located between the wheels and in a much lower position than on the normal motor cycle, ease of control, apart from comfort, is greatly increased.”

Throughout the company’s history, O.E.C. production was subject to fluctuations related to its location in a major British port city.

“From the start,” says Shelley, “the company had a small core of permanent employees, but benefited from its proximity to the Royal Naval dockyard in Portsmouth, which famously had a large ‘floating’ workforce of casual labor who would be taken on when the fleet was in and laid off when they sailed.

“O.E.C. would seize the chance to take on these skilled, but laid-off workers to help them construct a batch of motorcycles, and this practice of making batches of machines when the cheap workforce was available characterized the entire life of the O.E.C. enterprise. It did, however, lead to a very high standard of paint finish as demanded by the Navy for their ships, which O.E.C. enjoyed on their motorcycles.”

While experimenting with alternatives to the traditional motorcycle, O.E.C. continued selling more-conventional machines, mainly using engines from Matchless. And that relationship to the Matchless brand was strengthened when legendary motorcycle rider and dealer Stanley Glanfield bought the company in 1937.

Shelley writes, “Glanfield had famously circumnavigated the globe with a friend in 1927 riding a pair of Rudge Whitworth sidecar outfits, and they co-founded vehicle dealership Glanfield Lawrence.”

Shelley notes that the relationship with O.E.C. was convenient, since the motorcycle factory was literally next door to the Glanfield Lawrence dealership in Portsmouth.

“Keeping an eye on things,” he says, “Stanley would make an occasional unannounced appearance at the O.E.C. works through a small door connecting his shop to the O.E.C. works, much to the consternation of the O.E.C. staff!”

But the new ownership was not widely promoted, since it might create conflicts with other shops selling the company’s bikes.

“Big dealerships like Pride & Clarke would not have been eager to continue selling O.E.C.s if they had known they were owned by a rival dealer,” Shelley says.

Under Glanfield’s direction, O.E.C. began to source even more of its components from AMC, which was formed in 1938 as the parent company of Matchless and AJS. Shelley notes that O.E.C.s from this era may incorporate the company’s own Duplex forks and an improved version of its Rear Springing system, “But the center of the bike is pure AMC.”

Shelley indicates this actually marked the heyday for the company’s production, with most surviving O.E.C.s being AMC-based machines built in the late 1930s. And, he says, those bikes have held up well over the decades.

In its final years before World War II, O.E.C. sourced many of its components from AMC, the parent company of Matchless and AJS. As a result, the company’s machines, like this 1938 500cc Commander, bear more than a passing resemblance to AMC bikes of the era, except that they incorporate O.E.C. touches, like the Duplex Steering front fork. Courtesy Martin Shelley.

Shelley has firsthand experience with the brand’s durability. When he was riding his 1938 O.E.C. Commander a few years ago, he rear-ended a Jeep Cherokee that stopped without warning in front of him. The Duplex forks popped rearwards and destroyed the headlight and front fender, but the forks were quickly realigned and he was able to ride the bike home.

1939 would be the final year of prewar production for O.E.C. With the outbreak of World War II, the company’s factory was converted to production of war equipment, most notably special parts for the British Navy’s infamous “Panjamdrum,” a rocket-powered beach assault weapon that was designed to create a tank-sized hole in German defenses. The device consisted of a pair of 10-foot wheels that would spin under rocket power, speeding up the beach to crash into enemy structures at speeds of up to 60 mph. At that point, a 4,000-pound load of high explosives would go off, clearing the way for the invading soldiers. After a series of unsuccessful tests, the project was abandoned.

Production of O.E.C. motorcycles resumed in 1949, with a line of lightweight utility machines powered by two-stroke Villiers engines. Notably, those bikes continued the company’s tradition of using welded frames without lugs. O.E.C. also offered a range of light sidecar bodies with welded-steel frames paneled in aluminum.

By 1954, motorcycle production had dwindled to a trickle, and O.E.C. diversified into, of all things, the furniture business. But, as Shelley notes, a portion of the company’s engineering heritage remained, as their chairs and tables were made from welded tubular steel, with laminated seats and tabletops.

It was, unfortunately, this furniture enterprise that contributed to the demise of O.E.C. Having landed a large contract to furnish the cafeteria at Ford’s massive car factory in the city of Dagenham, O.E.C. struggled to bring its labor-intensive fabrication in line with the scope of the job. In the end, the company was unable to fulfill the contract and went under in 1959.

And with that, a British motorcycle manufacturer with a history of thinking outside the box was lost.