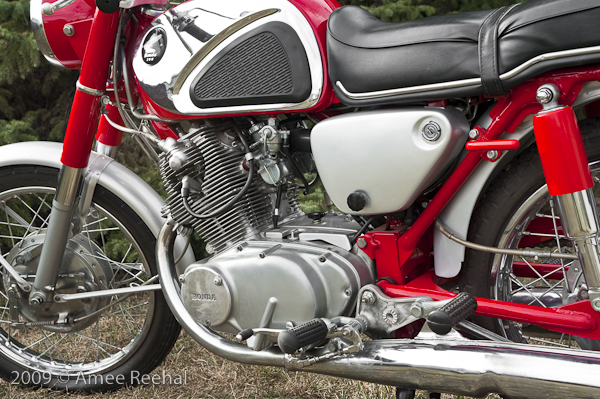

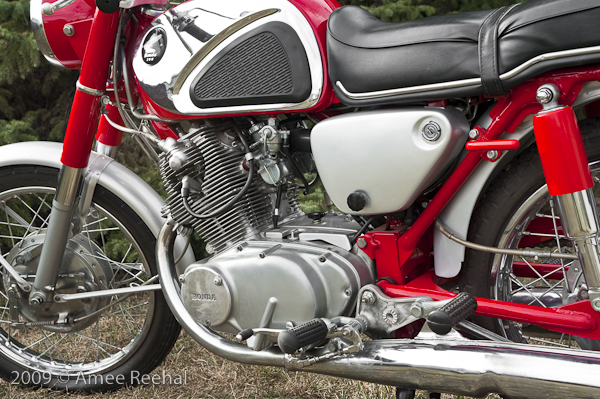

Wade Youngman’s 1966 Honda Super Hawk. All photos courtesy Amee Reehal.

Wade Youngman’s 1966 Honda Super Hawk. All photos courtesy Amee Reehal.

Story first published in Inside Motorcycles, Issue 13/01.

In 1959 Honda changed the way many people thought of motorcycles – and motorcycling — when they introduced their clean and quiet machines to North America.

And it was in 1961 with the CB72 Honda Hawk, a 250cc motorcycle, and its larger brother the CB77 Super Hawk at 305cc, that some rather unique features became available in mass-produced machines. An inclined vertical twin engine that could be revved to 9,200 r.p.m powered both models. The bikes included 12-volt alternator electrics, electric start, chain-drive overhead cams and wet sump lubrication. The Super Hawk proved most popular of the two bikes, and thousands of first-time riders cut their teeth aboard the model.

Calgary’s Wade Youngman (we featured his 1973 Kawasaki Z1 900 in issue 1208) was aware of the significance of the Honda Super Hawk. So when he got a call from a friend who told him he’d heard of an old Honda for sale, Youngman got the number and called the owner.

“The story was this had been his son’s bike, who had bought it brand new and rode it for a while,” Youngman says. “But he was on a trip down in Montana when he fell over on it, and it came home and into the back of the garage where it sat for years. That wasn’t a big deal until he retired and wanted his garage space back – he was working on a big Chrysler Imperial.”

When Youngman came along in 1997 he didn’t know the bike he was going to look at was a Super Hawk. He arrived at the garage where the bike was stored – buried behind some sheets of plywood – and the owner uncovered the Honda. “I knew right away exactly what it was,” Youngman says. “(The owner) said the motor was seized, and that he’d tried to kick it over. But he didn’t know that the Super Hawk kicks forward.”

When Youngman came along in 1997 he didn’t know the bike he was going to look at was a Super Hawk. He arrived at the garage where the bike was stored – buried behind some sheets of plywood – and the owner uncovered the Honda. “I knew right away exactly what it was,” Youngman says. “(The owner) said the motor was seized, and that he’d tried to kick it over. But he didn’t know that the Super Hawk kicks forward.”

The Super Hawk does feature an electric starter, but also employed the forward rotating kicker as a backup to fire the all-alloy engine. With its 305cc’s, the twin-cylinder engine produces 28 horsepower at 9,000 r.p.m. Lubrication is via wet sump, and the oil used in the engine also looks after the unit-construction four-speed gearbox, clutch and primary chain. A single overhead camshaft is chain-driven, with the drive sprocket placed directly in the middle of the crankshaft. Twin 26 mm Keihin carburetors feed fuel to the forward-canted engine.

A tubular steel frame with a large diameter backbone sees the engine employed as a stressed member, and features swingarm rear suspension and hydraulic forks up front.

The Super Hawk had a six-year model run, from 1961 to 1967. Production stopped in ’67, but Super Hawks were still available through to 1969. Super Hawks were replaced in 1968 by the CB350. In the U.S., 3,479 250cc Hawks were sold between 1961 and 1966. And between 1961 and 1969, 72,396 305cc Super Hawks were sold. In 1964, $665 would buy the CB77 brand new.

Youngman got his project Super Hawk for $125. Sounds like a steal these days. “The bike was in pretty good shape, but there had been a few modifications to it. There was a rack on it at one point, and somebody had welded an extension on to the shift lever to make it a heel-toe shifter.” There were dings and some road rash from when it went down, notably on the forks, front fender and the chrome gas tank panels. The handlebar control levers were broken and most of the rubber pieces were gone.

Youngman got his project Super Hawk for $125. Sounds like a steal these days. “The bike was in pretty good shape, but there had been a few modifications to it. There was a rack on it at one point, and somebody had welded an extension on to the shift lever to make it a heel-toe shifter.” There were dings and some road rash from when it went down, notably on the forks, front fender and the chrome gas tank panels. The handlebar control levers were broken and most of the rubber pieces were gone.

Armed with an old parts book and a Honda parts microfiche Youngman went over the bike and made a list of items required to bring it back. The Internet was just starting to blossom when he began the project, and there weren’t as many ways to find parts for old motorcycles. Using sources discovered in Walneck’s Classic Cycle Trader he phoned and sent faxes to many different suppliers, mainly in the U.S.

Remarkably, the mufflers on his Super Hawk were in fine shape. Original Super Hawk mufflers in decent nick are rare, and reproductions today cost upwards of $700. Youngman cleaned and detailed one piece after another. It soon became apparent that the whole bike needed to come apart – something he’d never done before was a complete restoration. Undaunted, he brought the frame to bare metal using paint stripper, wire wheels and sandpaper. He beat the dents out of the front fender, something else he had never done before, and says he was encouraged by the results.

Remarkably, the mufflers on his Super Hawk were in fine shape. Original Super Hawk mufflers in decent nick are rare, and reproductions today cost upwards of $700. Youngman cleaned and detailed one piece after another. It soon became apparent that the whole bike needed to come apart – something he’d never done before was a complete restoration. Undaunted, he brought the frame to bare metal using paint stripper, wire wheels and sandpaper. He beat the dents out of the front fender, something else he had never done before, and says he was encouraged by the results.

The chrome gas tank panels, though, were left to the experts at Alberta Plating. They removed the dents and applied the requisite finish to the panel, as well as the rear brake pedal, kickstarter and repaired shift lever. Nothing much else on the Honda required plating, but Youngman spent hours and even burnt out the motor on his grinder – equipped with buffing wheels — polishing all of the alloy components. Honda used a protective coating on its alloy brake plates and hubs, and it’s difficult stuff to remove. Youngman says he felt a bit like a chemist as he mixed and experimented with various stripping agents in an attempt to get to bare alloy in preparation for polishing.

A local motorcycle mechanic took the engine all the way down for inspection, and found nothing serious to fix. Youngman bead blasted the cases, cylinder and head, cleaned up the valve seats, and had the 305cc engine put back together with new piston rings, gaskets, o-rings and seals.

Super Hawks were finished from the factory in red, black, blue or white, and the frame matched the colour of the tank and forks. Fenders, side covers and the engine side covers were all painted the same silver colour. Youngman hired out the painting, and had reassembled the motorcycle in a little less than a year.

Super Hawks were finished from the factory in red, black, blue or white, and the frame matched the colour of the tank and forks. Fenders, side covers and the engine side covers were all painted the same silver colour. Youngman hired out the painting, and had reassembled the motorcycle in a little less than a year.

This is the point in the story where you’d expect to hear Youngman added fluids and a battery and pressed the starter button. It’s a bit of a standing joke now, but Youngman has never attempted to start the Super Hawk. It has oil. He has the battery.

“I just haven’t gotten around to it,” he says, and adds, “I know, it’s a lame excuse.” Regardless, he has a great example of one of the first motorcycles that really helped put Honda on the map.