History on a Post Card

This column was penned for my Pulp Non-Fiction column that appears in the Antique Motorcycle Club of America’s magazine, The Antique Motorcycle.

Motorcycling history surrounds us, even when attending a simple jumble sale. Read on.

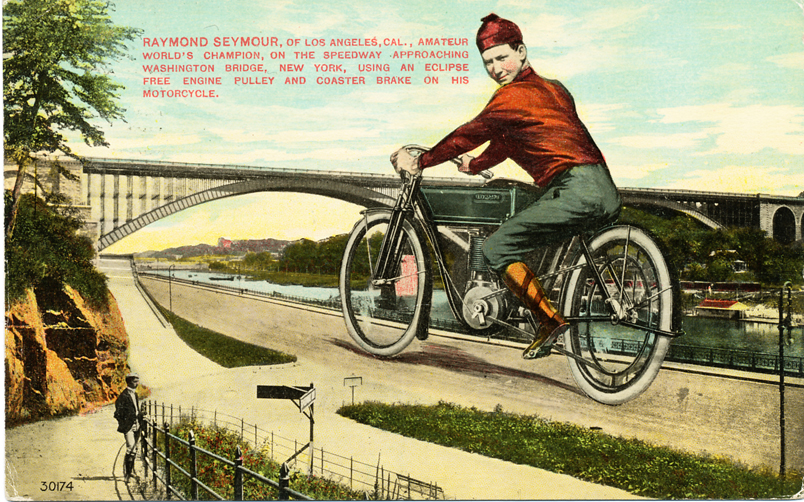

Self-promotion: On News Years Eve in 1910, the Eclipse Machine Co. sent out this post card (and presumably many others like it) to promote its line of motorcycle clutches among American riders. In the process, the company also shone a spotlight on a talented young racer of the era, Raymond Seymour.

Welcome again, fellow antique motorcycle enthusiasts, to Pulp Non-Fiction. Last issue’s column focused on Douglas motorcycles, produced in Bristol, England. For exactly half a century—from 1907 to 1957—Douglas built one of the most distinctive motorcycle lines in the world, based almost exclusively on the flat-twin engine design.

This issue, I’d like to change gears and highlight how a single post card led to some interesting discoveries about a company on this side of the Atlantic.

At a recent flea market, I stopped to visit a seller specializing in the post card trade. The cards were neatly categorized, and I thumbed through the Transportation file, discovering a gem—a little 5½” x 3¼” card that brings to light two different chapters of early American motorcycling.

The card features an image of a motorcyclist riding next to a river, with a caption reading: “Raymond Seymour, of Los Angeles, Cal., amateur world’s champion, on the speedway approaching Washington Bridge, New York, using an Eclipse Free Engine Pulley and Coaster Brake on his Motorcycle.”

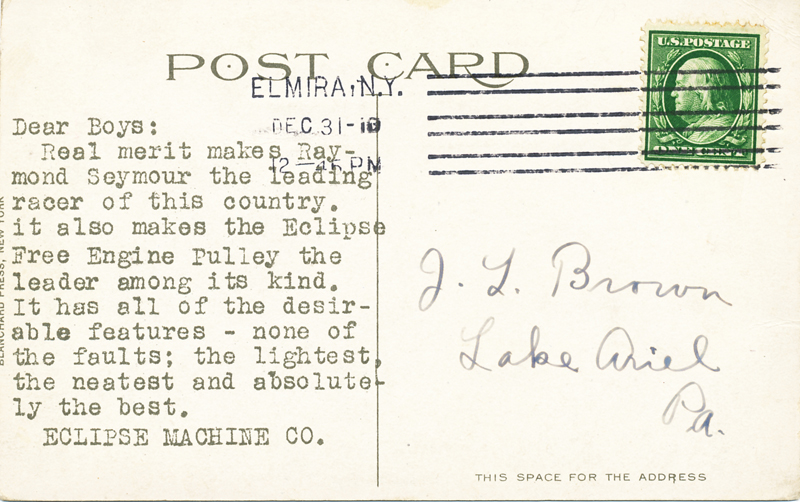

On the back of the card is the printed message:

“Dear Boys: Real merit makes Raymond Seymour the leading racer of this country. It also makes the Eclipse Free Engine Pulley the leader among its kind. It has all of the desirable features—none of the faults; the lightest, the neatest and absolutely the best.

“ECLIPSE MACHINE CO.”

The card I have was postmarked on December 31, 1910, in Elmira, New York, a town near the Pennsylvania state line in central New York State. But the bridge shown (not to be confused with the more famous George Washington Bridge) connects Manhattan and the Bronx in New York City. Nowhere is the brand of machine identified, although it bears some resemblance to a Reading Standard.

Here, though, is where the discovery of a single paper item can open up a whole chapter of history, thanks to the availability of information on the Internet.

As mentioned, there are two distinct areas of interest on this card. First is the Eclipse Machine Co., and second, racer Raymond Seymour.

A little bit of online research turned up the fact that the Eclipse Machine Co. started life in 1895 as the Eclipse Bicycle Company, based in Elmira. For the next four years, until 1899, the company produced bicycles. It then began specializing in the making of coaster-brake rear hubs offered to the public as the Bell Hub Bicycle Brake and, later, the Morrow Coaster Brake. In December 1902, the firm changed its name to the Eclipse Machine Company.

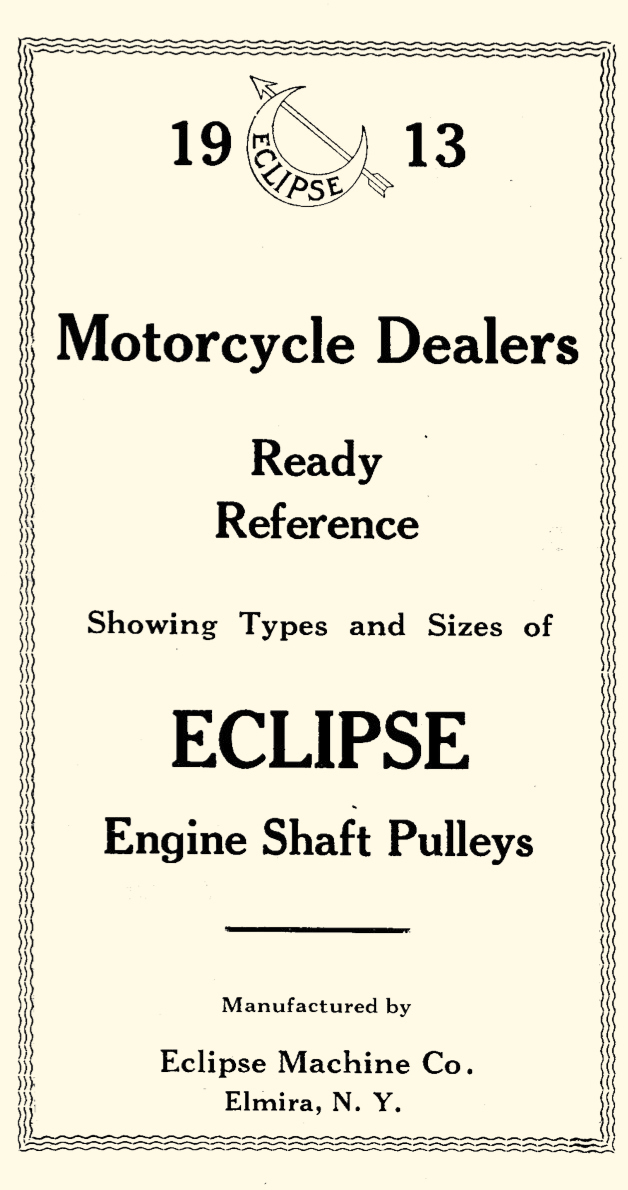

But one of the best resources for learning more information about the Eclipse Machine Co. turned out to be the AMCA’s very own virtual library, available through the Club website at www.antiquemotorcycle.org (you’ll find it by going to “Features” in the menu across the top of the page, then down to “Virtual Library”). This is a wonderful resource, consisting of hundreds of scanned historical documents such as parts manuals, original sales brochures, service guides and dealership papers. Best of all, AMCA members can download any of those documents free of charge.

I found a single document for the Eclipse Machine Co., in the form of a 1913 manual. Its full title is the “Eclipse Motorcycle Dealers Ready Reference Showing Types and Sizes of Eclipse Engine Shaft Pulleys.” It is a slim piece outlining the wide range of machines the Eclipse Engine Shaft Pulleys—what we would refer to as a clutch these days—would fit, including bikes from American, Armac, Curtiss, Detroit, Emblem, Excelsior, Flanders, Greyhound, Harley-Davidson, Haverford, Indian, Marvel, M&M, Merkel, Minneapolis, Pierce, Pope, Reading Standard, Sears, Spacke, Thor, Wagner and Yale.

In 1912, the Eclipse Free Engine Pulleys were fitted as standard equipment to Emblem, Merkel and Yale machines. The units were optional on Detroit, Haverford, Marvel, M&M, Pierce, Pope and Wagner motorcycles. And with numerous flat or V-shaped pulleys in a range of diameters, the clutch could be made to work on many other machines. Just a year or two later, the Eclipse clutch found its way onto machines fitted with two- and three-speed gearboxes, allowing a rider to shift gears.

Prior to the Eclipse clutch, belt-drive motorcycles used a tensioner pulley to connect or disconnect engine power to the rear wheel. But those systems required frequent adjustment and could not be used with the more reliable drive chains that were becoming common in the motorcycle world.

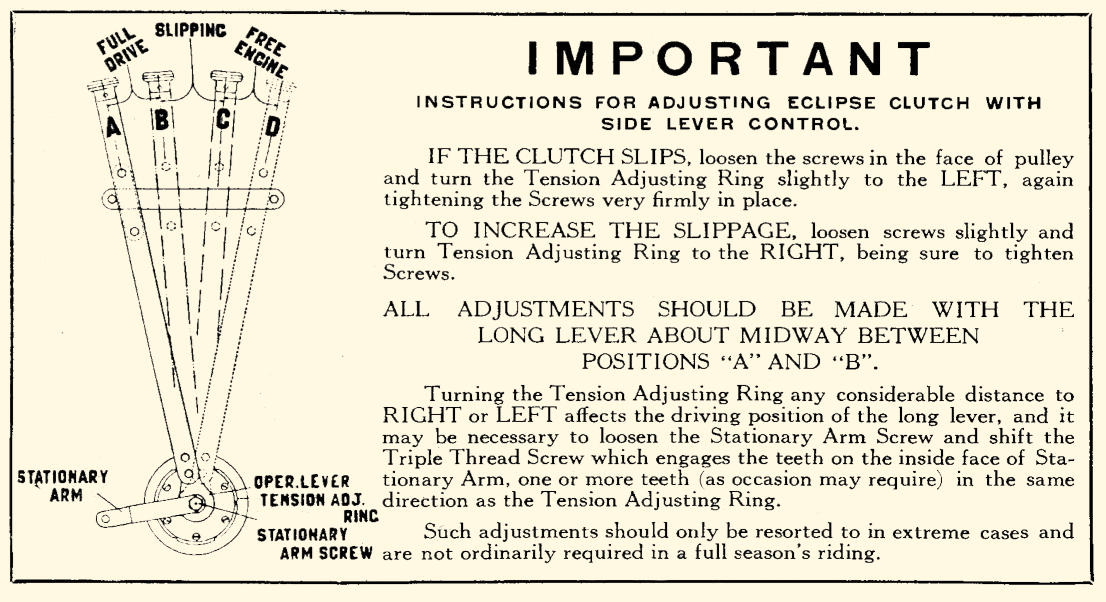

Courtesy AMCA Virtual Library.

The Eclipse clutch was designed very much like the clutches still used on most motorcycles, with a stack of “driving” and “driven” plates that could be squeezed together to transmit engine power to the final-drive belt or chain. According to the Dealers Reference, the Eclipse clutch could be controlled by either a side lever or a hand lever. Instructions for adjustment were the same for both: “IF THE CLUTCH SLIPS, loosen the screws in the face of pulley and turn the Tension Adjusting Ring slightly to the LEFT, again tightening the Screws very firmly in place. TO INCREASE THE SLIPPAGE, loosen screws slightly and turn Tension Adjusting Ring to the RIGHT, being sure to tighten Screws.”

One difference between the Eclipse design and modern clutches is the system used to compress or expand the clutch pack (thus connecting or disconnecting the engine from the rear wheel). Most modern clutches use a pushrod to separate the plates, while the Eclipse design used a helical worm-gear design that the company referred to as a Triple Thread Screw.

By the mid-teens, many manufacturers were developing their own multi-speed transmissions and clutches, which meant that Eclipse’s motorcycle market was drying up. But beginning in 1913, the company found itself playing a key role in bringing another convenience to the motoring world: electric starting.

Most early automobiles featured a hand-crank starting system, which made starting the engine an onerous and potentially dangerous task. In 1910, inventor Vincent Bendix developed an electric starter that required a helical worm gear very much like the one Eclipse was using in its motorcycle clutch. And he contracted with Eclipse to produce what would become known as the “Bendix” drive that connected the starter motor to the automobile’s engine.

In 1914, the Chevrolet Baby Grand became the first car offered with Bendix-designed electric starting, and the company sold 5,500 of the electric-start vehicles that year. By 1919, more than 1.5 million Bendix starters were in service.

Eclipse continued making sundry other mechanical components, including braking systems for automobiles, airplanes and bicycles. It’s unclear exactly when Eclipse stopped producing their motorcycle clutches, but they were likely finished in that line of business by the end of the teens.

In 1928, the Bendix Corporation acquired control of the Eclipse Machine Company, bringing an end to the Eclipse name. But the company’s innovation, in the form of its helical Triple Thread Screw, remained a part of most automobile starter designs into the 1960s (and in many motorcycle electric starters, too).

Now for the other interesting angle of research, and another perfect example of how pulp and computer mix. I had heard of racing legend Raymond Seymour, but turned again to the computer for information. Googling Seymour’s name, I found fellow AMCA member Pete Young’s excellent blosgiste, www.occhiolungo.com, where he had written a post about Ray Seymour and his contributions to the world of motorcycle board-track racing.

In 1909, at the age of 17, Seymour set many speed records aboard a Reading Standard motorcycle. During that year, Seymour rode his V-twin Reading Standard to record speeds of 72 and 73 mph at the Los Angeles Coliseum, before setting a world record for the mile at 47 seconds (76.6 mph) on the same track. Seymour raced on many other board tracks across America, but in 1910, Reading Standard stopped supporting racers. Seymour then moved to Indian, where that company provided him with one of its factory eight-valve machines.

Seymour was mentored by Canadian-born speed sensation Jake DeRosier, who was one of the first factory-backed racers. DeRosier was a star of American board-track racing, and in 1911 was the first American to compete in the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy races.

Under DeRosier’s tutelage, Seymour raced Indian motorcycles in 1910, 1911 and 1912 before retiring. Although he was still highly competitive, Seymour likely left the sport as a result of a board-track tragedy on September 8, 1912, at the New Jersey Motordrome.

Seymour was leading the race that evening when his Indian teammate, Eddie Hasha, lost control of his machine and crashed into the crowd, killing himself and six spectators, along with fellow racer Johnny Albright. The subsequent publicity over that tragedy put another nail in the coffin of board-track racing.

As Young points out: “Board track racers did nothing but go FAST. The bikes had one gear (top gear). They had no brakes, no clutch, nor suspension. They had no throttle; the carburetors were set to wide-open throttle all the time. If they needed to slow down, there was a button they could use to ground the magneto to the frame (stopping) the spark at the plugs. But of course the bike would continue to roll forward with its momentum. The motors spewed oil from the constant-loss oil systems, made worse by the holes drilled into the motor heads and barrels used to increase power. This oil went onto the rider, the rear tire, and onto the track. The front forks were set up to go straight, not to turn sharply. The tracks were extremely high-banked, almost like the wall of death tracks.

“(Racers) did all this with the technology of the time, i.e. Schebler carbs (aka the Controlled Leak), clincher tires that pop off the rim sometimes, primitive metallurgy in the connecting rods, pistons, chains, etc. And they went over 100 mph regularly. With this combination, riders had little chance to avoid the crashes that often occurred… During crashes the wooden track would give splinters up to 8 feet long. Riders wore minimal protective gear, typically a wool sweater and jodhpurs, maybe a leather helmet and puttees over their lace up shoes.”

Seymour was one of the lucky survivors of this culture of speed, but his life after retiring seems a bit of a mystery. Stephen Wright, noted author of the “American Racer” books, told me, “(Ray) was a fast rider, but he just wasn’t a very glamorous guy.” That could account for his relative obscurity later in life.

In 1913, one source suggests Seymour became a traveling representative for the Indian Motocycle Company, and Wright says that in the late teens, and perhaps into the early 1920s, Seymour had an Indian agency in northern California. “After that, he just sort of falls off of the map,” Wright noted.

All of that history stems from a small post card produced in 1910 by a company promoting its products through what is now a very quaint medium.

The Eclipse Machine Co. remained in operation in Elmira, New York, until 1928 , when the company became part of the Bendix Corporation. Photo by Paul Osborne