Dave Holmes with his 1977 Pontiac Trans Am SE. Holmes won the Long Distance award at the Summit Racing Equipment Firebird car show in McDonough, GA. Holmes had driven his car from Calgary, Alberta to attend, ensuring he was a winner as part of the Bandit Run 2010. Courtesy Dave Holmes.

Dave Holmes with his 1977 Pontiac Trans Am SE. Holmes won the Long Distance award at the Summit Racing Equipment Firebird car show in McDonough, GA. Holmes had driven his car from Calgary, Alberta to attend, ensuring he was a winner as part of the Bandit Run 2010. Courtesy Dave Holmes.

This story first appeared in the Calgary Herald Driving section July 9, 2010.

As a film, Smokey and the Bandit didn’t win any major awards.

Nevertheless, high -speed car chases and high-flying stunts helped make the movie a memorable one.

What makes Smokey and the Bandit even more memorable, however, is the black 1977 Pontiac Trans Am that plays a role in almost every scene of the film.

There were of course other actors in the movie, including Burt Reynolds, Jerry Reed, Sally Field and Jackie Gleason.

Here’s a brief plot synopsis: After accepting $80,000 to guarantee delivery of 400 cases of illicit Coors beer, Bandit (Reynolds) uses the Trans Am to draw police attention away from an 18-wheeler, driven by Cledus (Reed), that’s loaded with the goods. They’ve driven from Georgia to Texas to pick up the Coors, but by crossing the Mississippi back to Georgia with the suds they essentially become bootleggers – at the time, Coors product wasn’t allowed east of the mighty river.

But when Bandit picks up a wedding-ditching Carrie (Field), he also picks up some heat. Carrie left Junior, son of sheriff Buford T Justice (Gleason) at the altar, and Justice vows to track her down.

With hi-jinks and gags aplenty, the movie doesn’t offer much intellectual stimulation. But that’s OK, it is entertaining.

When Dave Holmes of Calgary ordered his own Trans Am in 1976 he hadn’t seen or heard of Smokey and the Bandit.

“My purchase of the car had nothing to do with the movie,” Holmes says of his black 1977 Pontiac Trans Am. Some 34 years later, Holmes still has the car.

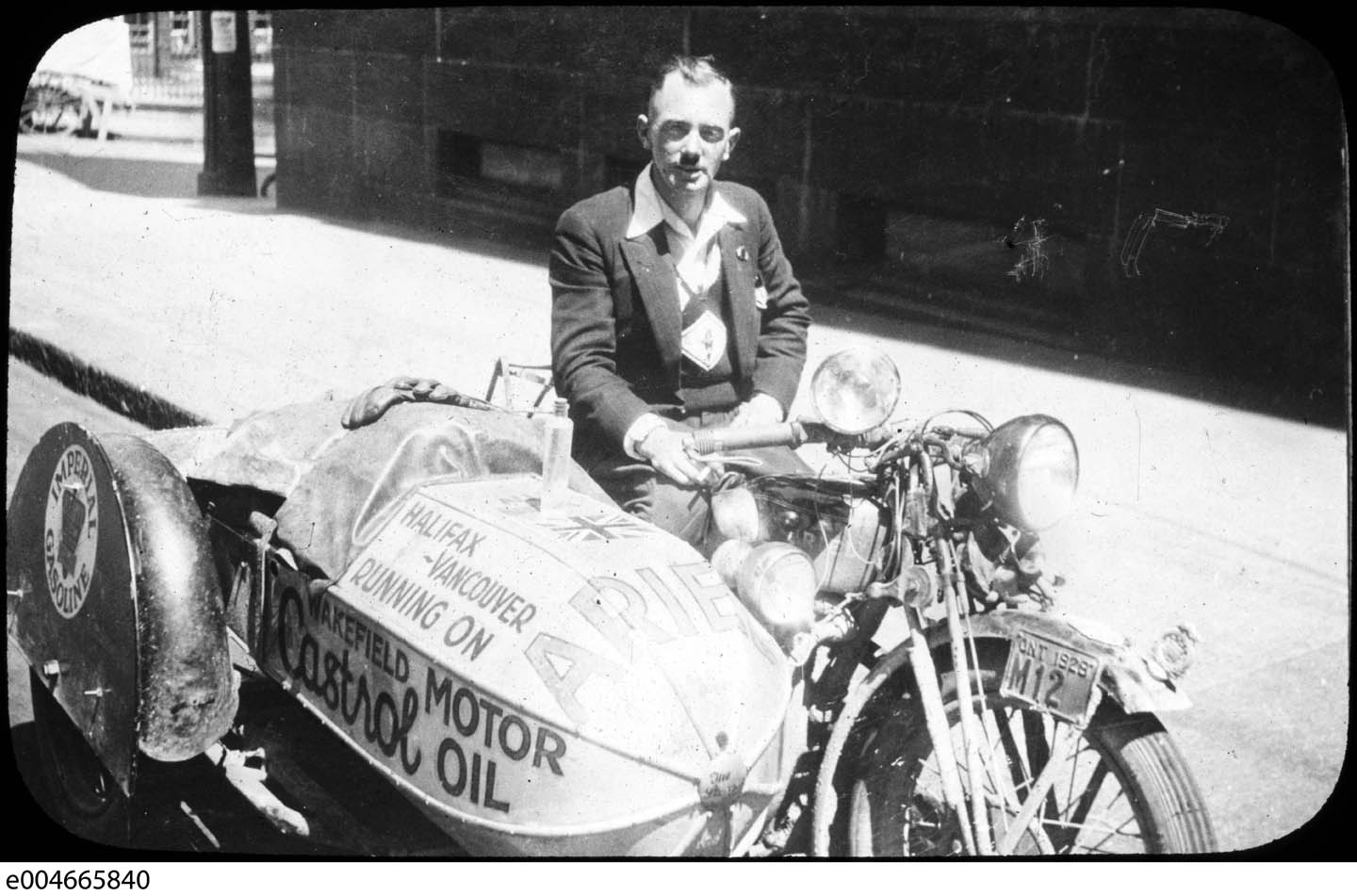

We have to step back to 1972 to pick up the story of Holmes and his Trans Am. After a motorcycle accident, Holmes lost the use of his right arm. He was 18 years old, and it took four years of court dates before Holmes got his insurance settlement.

With the money, he was going to buy a car. He’d always been a Corvette fan but he wanted to give his business to his uncle and cousin. They were family members who owned a Pontiac Buick dealership in Virden, Manitoba.

“The hottest car Pontiac had at the time was the Trans Am,” Holmes says. “I was talking to my cousin in the fall of 1976 – I ordered the car over the phone – and he mentioned they had a new special edition Trans Am available, and that’s what I ordered – with a red interior.”

Prior to Smokey and the Bandit, the car was simply known as a Trans Am LE, for limited edition. The LE was produced to commemorate Pontiac’s 50 th anniversary.

Pontiac built the LE for the 1976 model year, and the car featured the black paint, gold pinstripes and the huge decal of a bird, also in gold, spread across the hood. Another unique feature of the 1976 LE was the T-top glass roof hatches.

Selling successfully, Pontiac decided in late March of 1976 to continue the LE option into 1977, dubbing it the Trans Am SE, or special edition, to differentiate the two model years.

But then Smokey and the Bandit happened. In the summer of 1977, after the movie hit the screens the black Trans AM SE vehicles pretty much became immortalized as ‘Bandit cars’.

On May 24, 1977 Holmes flew from Calgary to Virden to collect his Trans Am. He paid $8,900 for the car, and he drove it every year, all year, as his daily driver. Even though he was 24 at the time, he says he never drove the car very hard, and always took care of it by changing the oil every 2,000 miles (3,200 km). He replaced brakes, tires and hoses, and kept it tuned up.

But in the winter of 1993 the car skidded on a patch of ice in his driveway and continued through his garage door. That’s when he decided to buy an SUV, and park the Trans Am for the winter months.

Holmes says he had the car painted in 1998, but bemoans the fact it was a mediocre restoration, complete with the wrong decal package. Plus, it started to rust again almost instantly; with the unsightly rot returning around the rear wheel wells and the back bottom corners of the doors.

“I got sick of looking at it like that, and I borrowed the money and got it done properly,” Holmes says. In 2004, rusty metal was cut out and new patches welded into place. A one-man shop in New Sarepta, Alberta, sprayed the black paint and positioned the iconic decals.

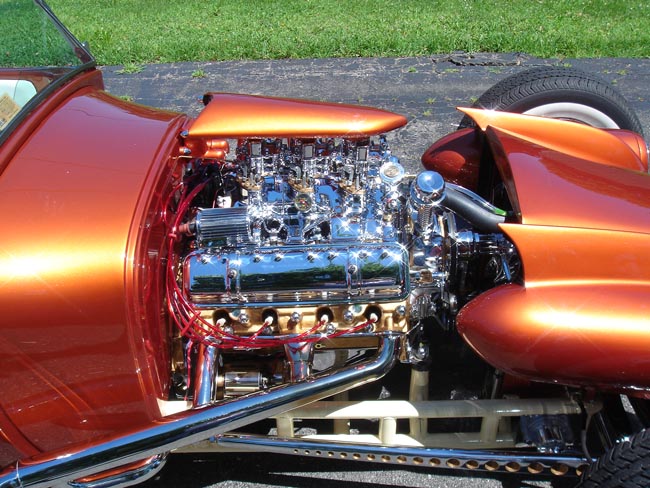

Most recently, Holmes had the engine pulled to chase down a leaking seal, and while the powerplant was out of the car the pistons and valvetrain were inspected. There was nothing wrong with the big 6.6-litre V-8 engine, which has logged some 189,000 miles (304,166 km).

While Smokey and the Bandit had nothing to do with his original purchase decision, Holmes now enjoys the connection. He’s attended two Bandit Runs, one in 2009 and again in 2010. The Bandit Run was first held in 2007 to commemorate the film’s 30 th anniversary.

Holmes drives his Trans Am from Calgary to the southern states to participate, and says he rolls his eyes when he sees vehicles unloaded from car haulers.

“They’re so much fun to drive around, and that’s the whole idea of having the thing,” he says. “I get honks and waves from truckers all the time.”