Calgary hits the Salt

Calgary has a burgeoning land speed racing community. This is a follow-up to my post of Sept. 21.

Thanks to Liz Leggett and Joanne Meyer for the photographs.

Aerotech Salt Liquor LSR. Photo Joanne Meyer.

More than just a couple of readers were interested in learning, well, more.

In this column of 14 September I wrote about three Calgary teams who built land speed racers and trekked to the Bonneville Salt Flats.

I made mention of two other teams, but their stories weren’t included.

To rectify that, here’s an accounting of Aerotech’s Salt Liquor 1934 Ford and The Rod Shop’s Wingin’ It belly tanker. In mid-August 2012 both were first time salt flat participants.

“We were in a pub in Kensington, having a pint and watching Speed TV,” says Dave Meyer, president of the Aerotech Group of Companies. “That’s when Reed said we should build a 1934 Ford and hit the salt.”

Reed Sutherland is an Aerotech employee, and according to Meyer, the team was formed that very evening. Within a week, Meyer purchased frame rails to get started on the build.

“That’s when my wife asked if I really thought this was a good idea, because none of us had ever built a race car before,” Meyer says. “I told her we could do this with Terry Graham’s help.”

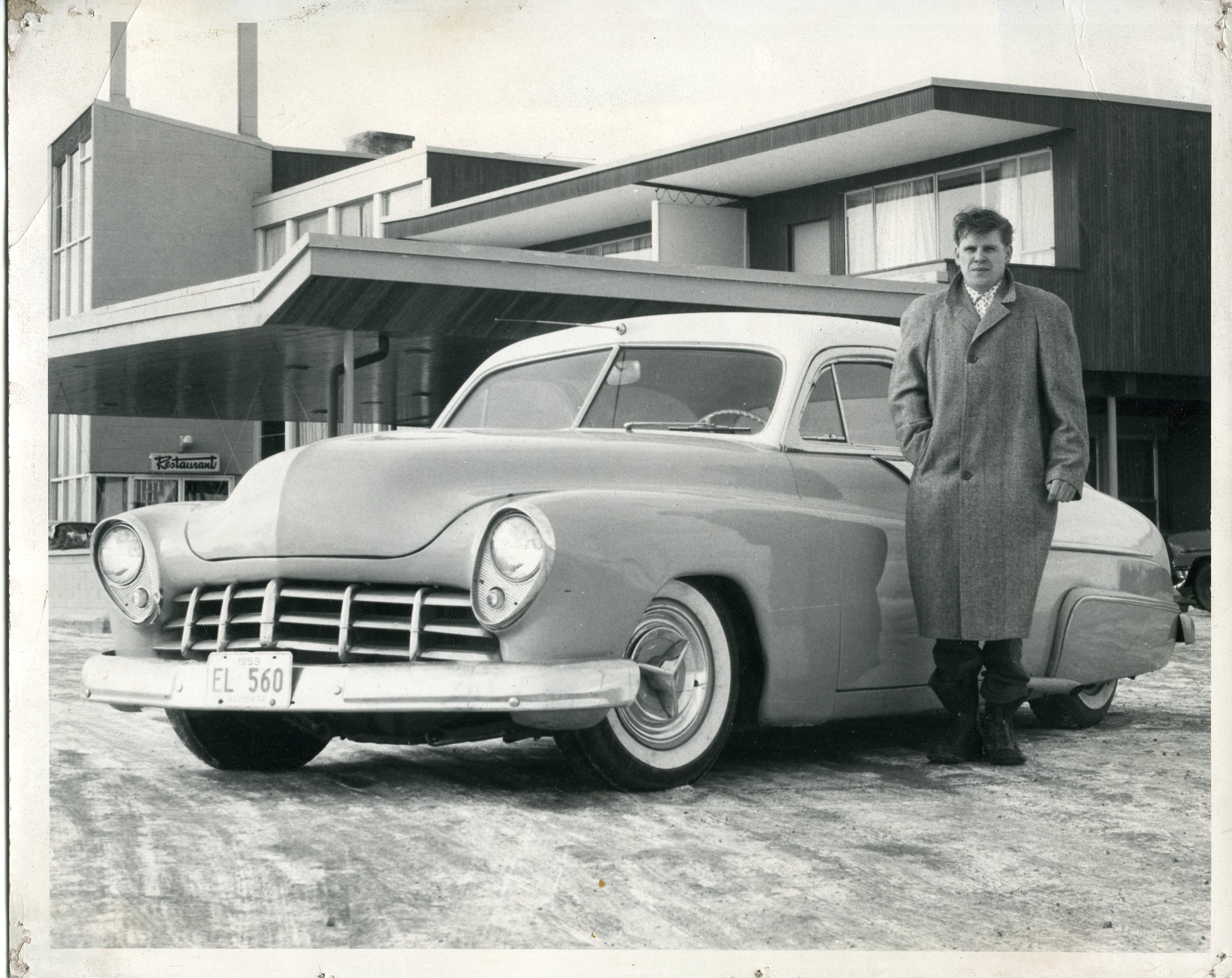

Since 1963 Graham’s been involved with building vehicles that go fast, from oval track cars to tractors. Graduating from SAIT’s aircraft maintenance program in the early 1960s, Graham soon had a job in Edmonton at Faulkner Aircraft.

“In Edmonton Ron Fernworn and I raced a hokey Buick, and then a flathead on the oval,” Graham explains. “Then, I moved to Calgary and we got friends and investors to help build Stampede Speedway.”

That oval track in north Calgary later became Circle 8 Speedway, and Graham went on to open Airport Welding where he built successful race vehicles, including an Indy car, for Frank Weiss.

Airport Welding is where Meyer apprenticed under Graham’s watchful eye.

Terry Graham on the salt. Photo Joanne Meyer.

“He took me right out of high school, and excluding my parents, nobody’s taught me more,” Meyer says. “Aerotech’s got 60 employees, and without Terry’s mentorship, we wouldn’t be where we are now.”

Every Tuesday evening and Saturday afternoon Graham, Meyer, Sutherland, Paul Jolicoeur, Trevor Buckler and Matt Latrace met to work on the car.

“It was kind of a slow process at first,” Graham says. In 2010 the team took what they had built down to Bonneville and ran it through tech inspection. Both the inspectors and other racers made suggestions, and when the car came back to Calgary the team got serious, extending the chassis and reconfiguring the front of the vehicle.

Essentially, Graham became the crew chief when he retired from his job at Calgary’s Valley Metal and focused on the car, which features one of his built-up 490 cubic inch Chevrolet engines, saved from his tractor racing days. Plenty of sweat equity from the team meant they were ready to tackle the salt in 2012.

Salt Liquor. Photo Joanne Meyer.

“I’d never sat in a race car before, and it was a little unnerving because we’d never even put (this one) into gear,” Meyer says of getting onto the salt. “The fastest I’d ever driven before in my life was 70 mph in the truck on the way down.”

In all, 10 runs were made in the 770 horsepower Salt Liquor car in the AG/CC class. The best run was 318.7 km/h (198 mph) before they dropped third gear due to some shifting issues. Right now, the car’s apart and the gearbox is being rebuilt while the engine is on the dyno for more tuning. They’re going back in 2013, but are happy with their novice attempt.

Meyer says, “I think we did quite well for our first year, and Terry guided us through the process. Any credit rides on his shoulders.”

The other Calgary team hitting the salt was Tom Racz and his crew at The Rod Shop. They built a lakester from the wing tank of a Canadian T-33 jet trainer to compete in the XF/GL class.

The Rod Shop’s Wingin’ It lakester. Liz Leggett photo.

They got stated by cutting the tank in half, establishing the chassis perimeter, and planning just where the engine, transmission and rear differential would go. A chassis built of rectangular rails and round steel tubing soon took shape, with the 286 cubic inch stroked and bored flathead Ford at the rear of the vehicle.

In 2011 The Rod Shop planned to finish the build, get to Bonneville, pass tech inspection and run on the salt.

They ran out of time and did not have a completely finished vehicle, but just like the Aerotech team, took the car down for tech inspection.

They learned some lessons, and in order to become a record contender Racz replaced their single-speed gearbox with a two-speed Ford transmission. That change meant the rear of the chassis had to be lengthened some 10 cm.

Both the Ford flathead and the gearbox were built up by Calgary’s Trevor Landage – and the car was still being worked on this year when it was loaded for the drive to Bonneville.

“Just before we crossed the border the turbo blew in our Ford F-250,” Racz says. “But we ran like that to Ogden, Utah, where the dealership looked at the truck. We spent the day working on the car in their parking lot, getting all of the little things finished.”

When the team got to the salt flats they passed tech, but they had to replace their six-point harness with a seven-point belt, and Racz had to purchase fireproof underwear – seriously – before he’d be allowed to run the car.

Wingin’ It lakester. Liz Leggett photo.

Racz went through the rookie orientation, which he said gave him a bit of confidence before his first attempt at a two-mile run.

“It was our first run and I couldn’t get the car in gear,” Racz says. “So, we shut the car off and put it in gear, then started it again. Well, it started to roll immediately, and I thought the push truck was already getting me up to speed.”

Little did he know that the truck was nowhere near, and the clutch was grabbing, sending him down the track. “I just went for it,” he laughs, “And about three quarters of the way through the run I remembered to breath.

“I can’t describe the feeling — when the run was over I just started laughing uncontrollably. It was the craziest, wildest most insane thing I’d ever done.”

With the clutch properly adjusted Racz started to get into a rhythm, and he says: “The thrill of the ride exceeded the fear of dying.”

Their top speed was 257.7 km/h (160.113) mph, and they were chasing a 315.4 km/h (196 mph) record. Back home, the team has pulled the engine for disassembly, rebuilding and tuning and plan to clean up some of the car’s aerodynamics before heading back in 2013.

Racz says, “It was the most incredible time of my life, and I can hardly wait to do it again.

Here’s another little note.

If you go fast enough on the Bonneville Salt Flats you join a select group of folks — there’s a 200 MPH Club, and there’s also a 300 MPH Club. There are two Canadians in the latter fraternity, and they’re both Calgarians.

In 1996 Les Davenport made a 314.563 mph run in an AA/lakester (501 cubic inch or larger engine).

Most recently, in 2008, Curtis Halvorson of Extreme Engine Development helped an American family construct a diesel streamliner. Not only was he responsible for the drivetrain, he was also asked to drive the vehicle.

Halvorson says, “On the eighth and ninth run of the car I was able to eclipse the existing 36-year-old record of 236 mph with a new record of 307.876 mph. The next year (2009) I was still driving the car and at the same event, upped my existing record to 341.167mph with a terminal velocity of 353 mph on my one pass.

“This number made me the fastest Canadian in history on land as well as the fastest diesel on the planet.”